The World

A week ago my last living grandparent died. Annie Atkins Clark was 98 years old, and up until just a few weeks ago, she’d been healthy, sharp, and full of life.

The World Playlist

A week ago my last living grandparent died. Annie Atkins Clark was 98 years old, and up until just a few weeks ago, she’d been healthy, sharp, and full of life. 98 years is an incredible run, and my grandmother lived her life fully and joyfully. She was ready to go, and she left it all on the field. But I have to admit that some part of me thought she’d live forever.

Annie was my father’s mother.

My dad would say he “isn’t sentimental,” but he is, in fact, extremely sentimental — no matter how many times he’s watched Field of Dreams, for example, if it’s on TV, he’ll watch it until he’s sobbing through the credits. No, my dad isn’t “unsentimental,” but he is uncomfortable with big, unpleasant feelings. He is a Boomer in a very real sense. My grandfather fought in World War 2, then came home and had seven children even though he had no religious incentive to do so. There were too many children for anyone to take up too much space, and my dad developed an outlook on the world that can sometimes feel both stubbornly optimistic and painfully pragmatic.

He’s been preparing my brother and me for our grandparents’ death for our entire lives. I think he believed that being straightforward about the finite nature of life might alleviate any anxieties we had about it. I don’t know that I needed to be braced for my grandmother’s death for the last 38 years, but it was a strange sensation for me to acknowledge that after all those years anticipating it, she was finally gone.

In the past few days, when I’ve asked my dad how he’s feeling, his knee jerk response is to be positive, to talk about the incredible life she lived, how many people she loved and who loved her. But I detect sadness in his voice when he talks about how strange it is to drive home from work now without talking to her as he’s done every day for years. I’m sure it’s annoying to get advice from your child, but I’ve reminded him more than once that it’s okay to miss your mother, to grieve that loss, no matter how old she was when she left us.

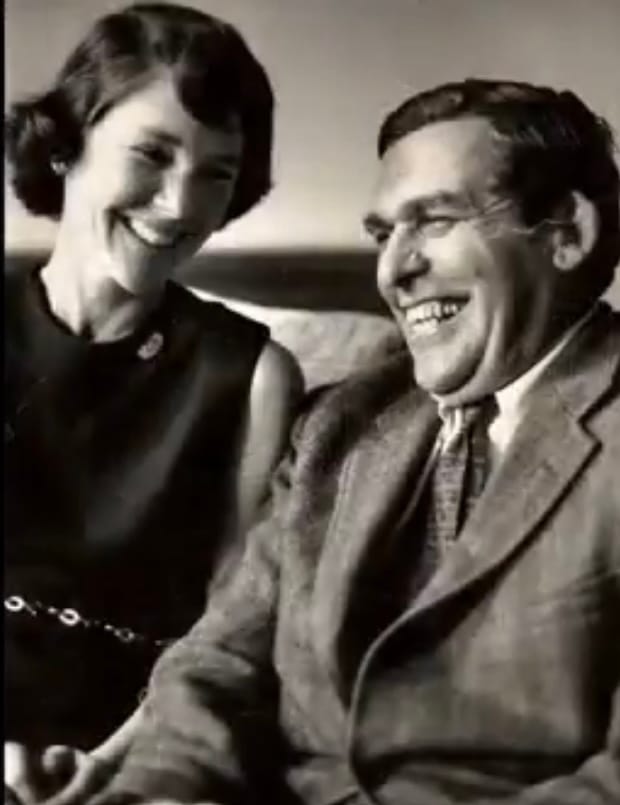

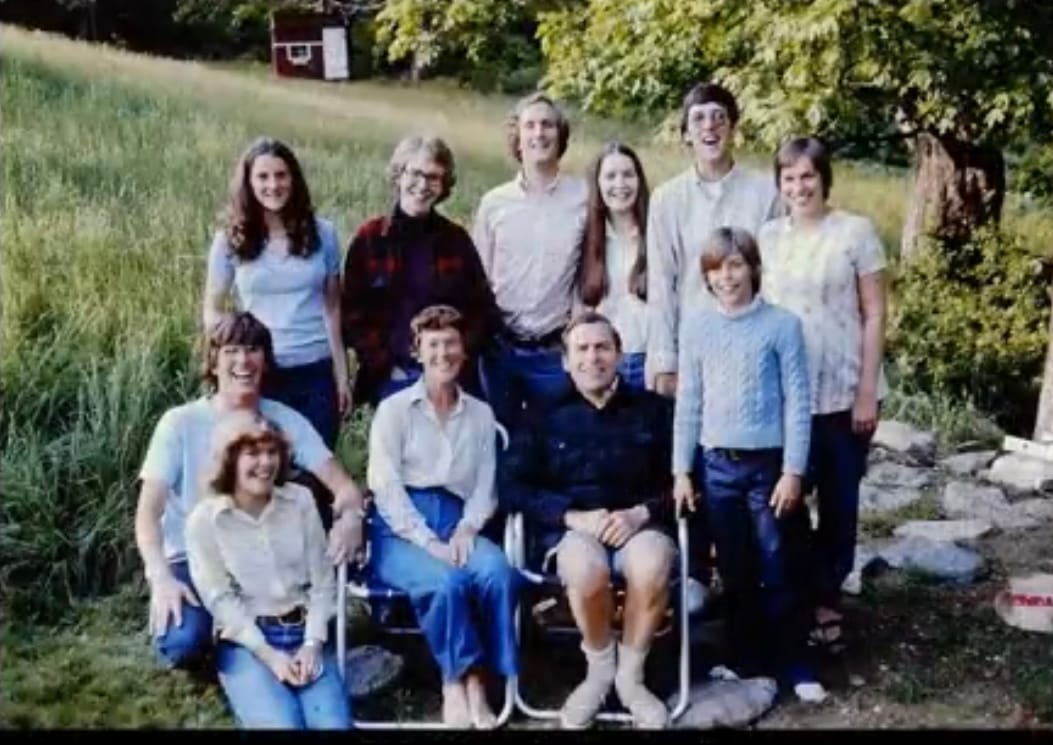

She was a lot of things — a prolific matriarch, mother to seven children, grandmother to eleven, great-grandmother to fifteen and counting. As a young woman, my grandmother was a model, photographed by Richard Avedon, among others. She was engaged to a Catholic for a time, a union her mother frowned upon (“He’ll want to have a million children!”), and when that engagement ended, she married my grandfather, an agnostic law professor, with whom she had seven kids. She played field hockey at Vassar, and later became a physical education teacher and a coach at the Foote School in New Haven.

My grandmother, the model.

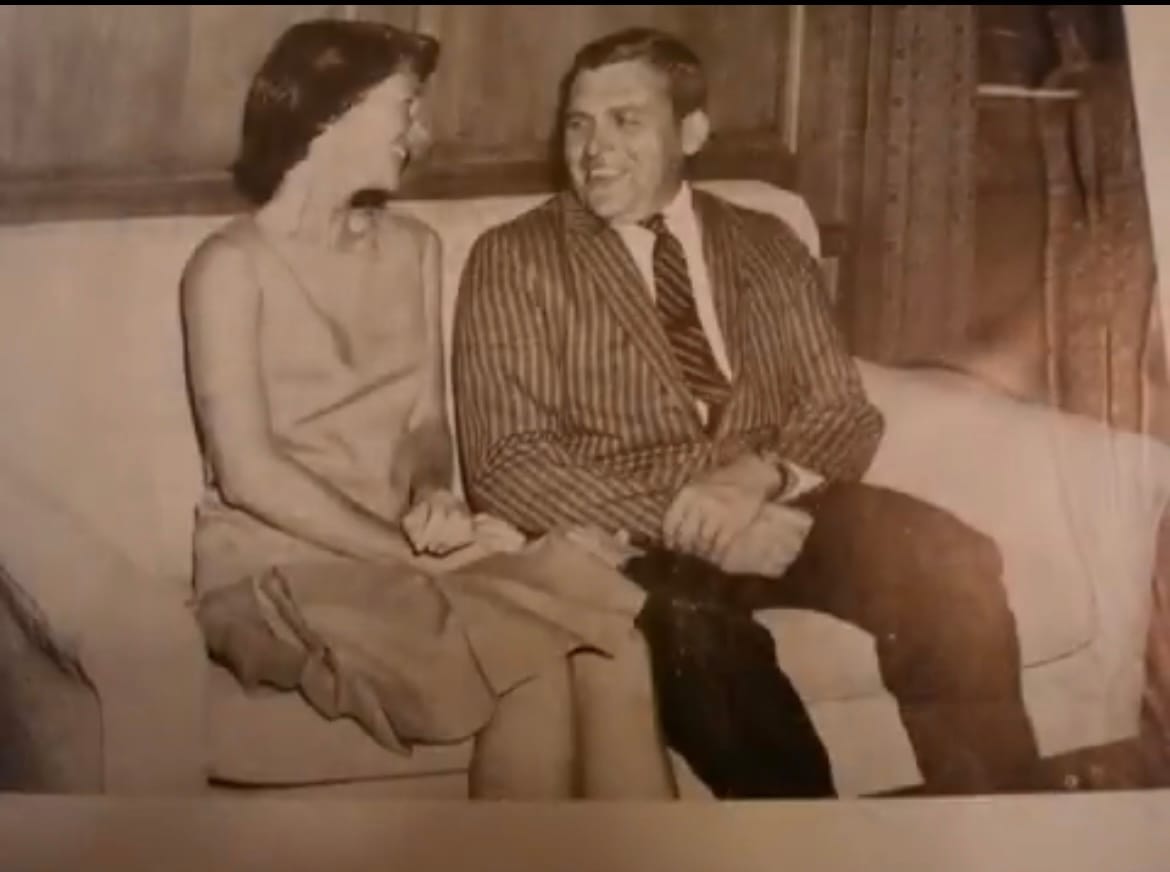

Her husband, my grandfather, Eli (my namesake) was larger than life. By the time I was born, his knees were already failing him. There are a handful of pictures of me as a child on his shoulders, but even in my earliest memories, he is planted firmly in a chair, holding court. Eli was a professor, Master of Silliman college at Yale, and he loved to tell stories. He would sit in a big red arm chair in the living room of their home in Vermont (a chair that even over a decade after his death is still “his chair”), and we would all gather around him to hear his stories. When Eli was alive, my grandmother was often in the background, a supporting character, revered and respected, but secondary to the sheer force of nature that was my grandfather.

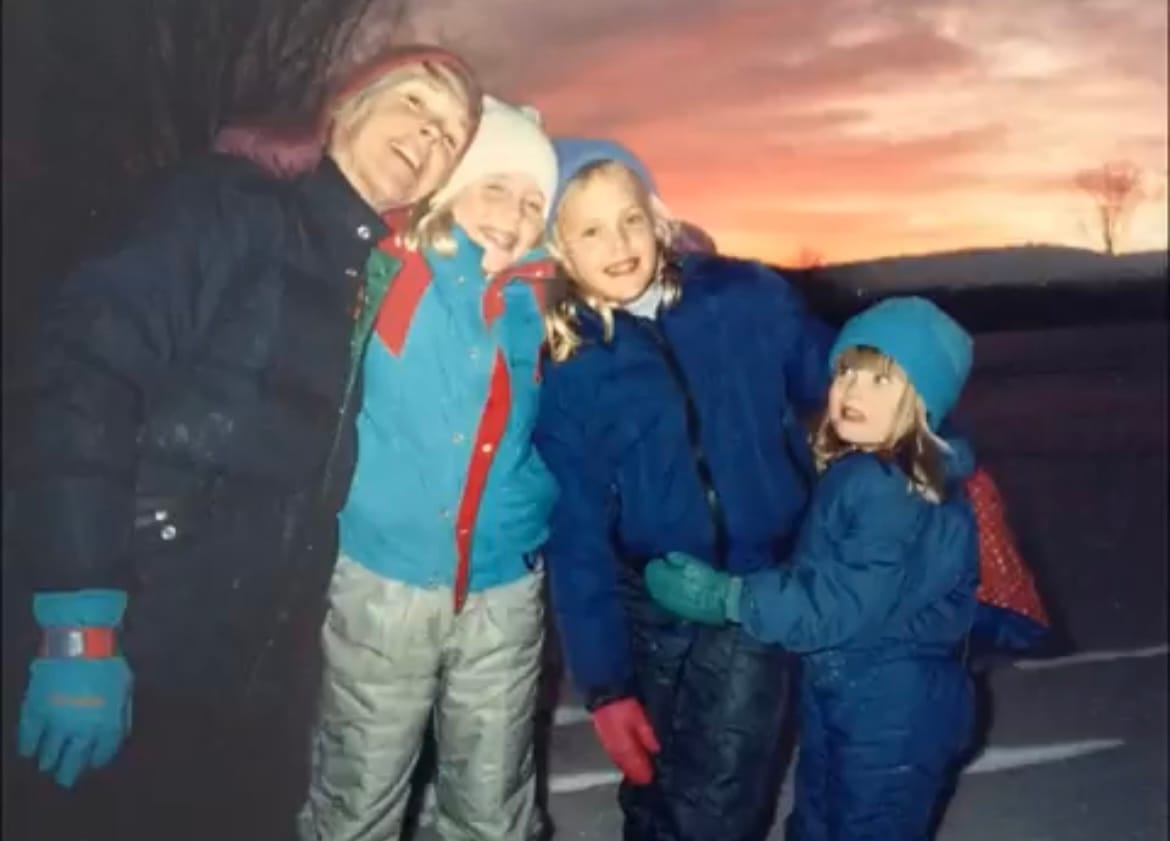

My family is loving, hilarious, and sprawling, stretched out over the United States, but tethered to the family home in rural Vermont.

I grew up army crawling through the fields playing kick the can with my dad, catching frogs in my grandparents’ pond in the woods on their property, performing musical revues with my cousins. Once, when my brother was about six years old, he bet my grandfather that he could catch a chipmunk. My grandfather balked and said, “If you can catch a chipmunk, I’ll give you a hundred dollars.” A few hours later, my brother had jerry-rigged a Tupperware trap and caught a chipmunk and my grandfather eventually paid up. One summer, my grandmother helped me dye my hair blue with manic panic hair dye which pissed off my mother and filled me with joy.

Now, my children say that Vermont is their favorite place on the planet, and every summer, they hike in the woods and catch frogs in the pond, and my dad holds court in that big red chair.

Life is cyclical, and The World card reminds us that every ending is a beginning. The World is a celebration, a big “yes” from the universe, a victory or completion.

I have trouble with endings. On the one hand, there’s no better feeling than the weight of pages you’ve written freshly printed in your hand. The happiest I ever am is the moment when I’ve sent something out into the world, the moments before it will be read and picked apart by someone else, the moments when it is still mine, when it is filled with all of my hopes and optimism. Before anyone has read it, there’s still a possibility that it’s perfect.

On the other hand, how do you know when something is done? The creative process is fickle and subjective. My last play was “done” when we opened, and I felt certain that every single word was necessary, carefully placed, and in the right order. But when it came time for a second production, things changed as they inevitably do. Theater is alive, which is what we love about it, and so nothing is ever done. Since those two productions, I’ve written an adaptation of that play, and it changed forms again. And if I’m ever able to make that film a reality, it won’t be done being written until the final cut is locked.

Writing, like life, is a constant process. Sometimes it has to “end” in a way that is no longer in your hands. One of the things I appreciate about television is the speed and velocity of the work. Television is necessarily collaborative (there’s just too much to do for any one person to do it), and the tight timeline means that you cannot tinker endlessly, because the machine must be fed. There is a date after which nothing else can change, and that is both scary and a relief.

Life, once its over, becomes a story, viewed from multiple points of view. I could tell you the story of my grandmother’s life linearly, as a series of facts, or I could tell her story in anecdotes from the people who knew her. When my mother was a teenager, she came to visit the Vermont house for the first time (she and my dad have been together since they were 13 years old), and she saw Annie and Eli coming back from the pond and asked if they had had a nice swim, and my grandmother replied, “It was glorious, we made love in the sun.” My mother was raised super-fucking-duper Catholic, and this was shocking and exhilarating for my mom to hear from any middle-aged woman, much less her boyfriend's mother.

Mostly, people are remembered in pieces, personal experiences spread across the many people they came in contact with. It’s impossible for one person tell the complete story of another’s life. But I can tell you the impact she had on me. My grandmother took me to my first Broadway show, she came to see every production I was ever a part of. Once, when she saw a play I had written, she remarked about my use of curse words. She told me she thought cursing was lazy writing and a bit childish (I disagree), and she told me she loved the play, but she could have done without all that. Then she told me a story about graduating from Vassar, how she rolled down the windows of her car and screamed into the wind “Shit! Fuck! Asshole!” and then she “never said those words ever again.”

I think about how progressive and kind she was, the way she continued to learn about the world until the day she died. My grandmother’s heart was big and wide, open to the possibility that the way she’d been taught about gender or sexuality, for example, was not the only way of being. My grandmother didn’t like curse words, but she loved people, and she was fiercely protective of all members of our family and our wide net of friends. She had strong opinions, but she was not judgmental of others. She had her own relationship with a god of her understanding, in spite of the volume of my grandfather’s beliefs.

She didn’t pull punches which sometimes hurt my feelings, but I’ve come to see her criticism as an acknowledgement that she took me seriously. She was not perfect, and I want to be able to remember these things about her too, because she was a person, a full person, complicated and complex, and a part of the ongoing story of my life.

When a person dies, their story doesn’t end, just as The World card indicates completion and the beginning of a new cycle. In some ways, death is the end of the first draft of your story. Eulogizing a person is a polish draft, an edit of the story for a broad audience, a way of wrapping things up, contextualizing, deciding collectively what to remember. When we memorialize, we are rewriting a story that is still in progress. After death, our story lives on in the lives of the people who remember us.

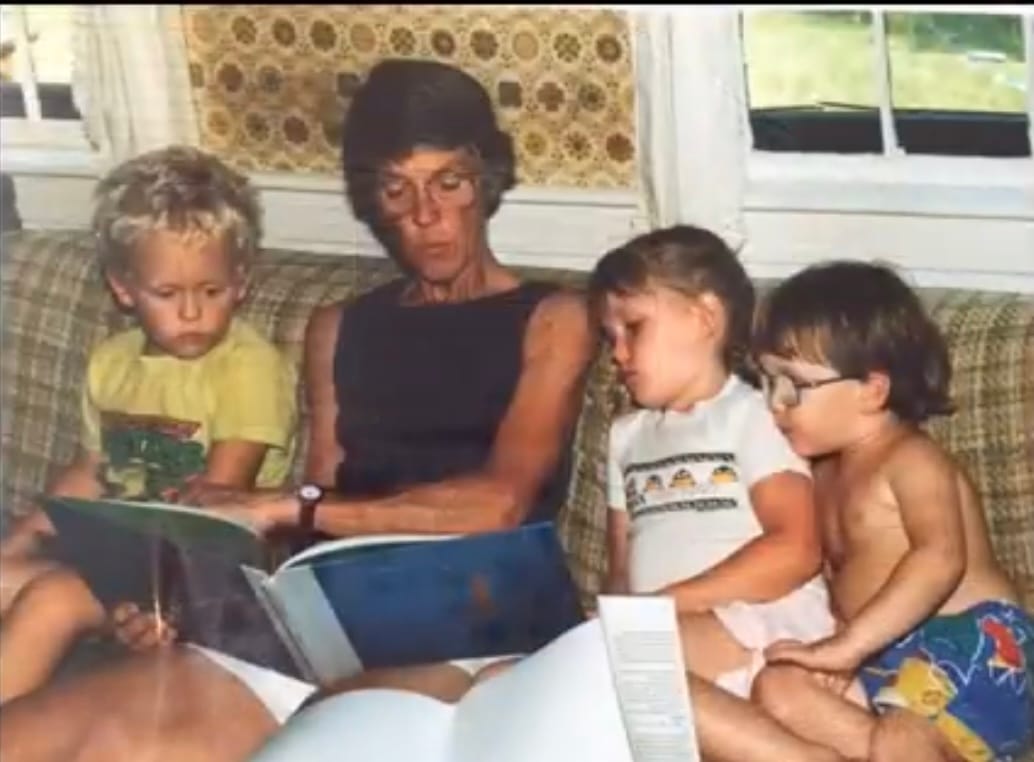

Just a few of the people who have stories about my grandmother.

My story is still being written and therefore, my grandmother’s is too.

My dad likes to tell a story about something my grandmother told him when I was born. In her infinite wisdom (she had seven children after all), she wanted him to know that I was going to be whoever I was going to be. She said that every time she held one of her babies she knew that her job was to guide and to love, but not to mold. She believed strongly in the personhood of children, that we had opinions and inner lives and that we were going to be whoever we were regardless of outside intervention. While other peoples' grandparents were being sucked in by the fear-mongering and bigotry of Trump, for example, my grandmother continued learning and expanding her capacity for understanding and acceptance.

I love my grandmother, I miss her. I’m grieving the loss of her, but I also think there’s almost no better example of a life well lived. The first draft of her story is complete, but new chapters are being written all the time by the people who loved her.

The World is a card of celebration, completion, and victory. And it’s an indication that the cycle is about to begin again.