The Star

A conversation with the other Eliza Clark, celebrated author of Boy Parts and Penance, about the creative process, our younger writer selves, hierarchies of power, the banality of evil, and our strange nominal connection.

The Playlist

In the story of the Major Arcana, the Star card follows the upheaval and earth shattering paradigm shifts of The Tower. The Star represents hope, optimism, and a renewal in confidence. The Star reminds you of that ineffable unique magic that makes you you.

My major Tower moment came in the form of an abrupt cancellation of a show I truly believed would run for years. We don’t have to rehash this, because honestly, I’m getting tired of hearing myself rehash my creative grief. We get it, Eli, boo hoo. I wouldn’t blame a single one of you if you were secretly thinking, I’ll give her something to grieve… Believe me, I’m as tired of myself as you are of me.

Though, since we’re both here reading a collection of my personal essays (I don't like the word "blog") and apparently I will not give it a rest, let me just say this: I do not recommend attaching all of your self worth to the success of a television show. I really thought I understood this lesson years ago, but friends, I did not. Writers, actors, directors, artists of any kind: we have to find joy and fulfillment in the process, not the outcome, because the outcome is out of our hands. We are not the marketing team, we are not the people in their houses deciding what they are going to watch, we are not the network executives who answer to CEOs of multi-billion dollar companies that do not just make television but also manage theme parks, sell computers, or bring anything you can think of to your door in under 24 hours. It’s honestly none of our business what happens to the work when we are done with it.

Okay. So the show gets canceled, which somehow surprises me, floors me, devastates me, and completely unravels my sense of confidence. I was thrown from the Tower I had built up around me. That Tower was built on many things — creative fulfillment, hard work, deep collaboration, yes, but also, if I’m being honest: ego, vanity, a sense that finally I would get what I’d always wanted. And what did I always want? Of course I want to be able to do great work, work I care about and feel passionate about and love, work that fulfills me, work that my collaborators are proud of, work that connects to an audience and makes someone feel seen. But underneath all of that there’s something else… A tickle in the back of my throat about acclaim, validation, success, and I don’t know, maybe even revenge...

On the darkest days in Toronto with Covid raging, my husband still depressed in bed at 3pm, and my kids far from everyone they know only to receive a small sliver of my time each day, there’s a fantasy in the back of my mind of why all this has been worth it. I’m picturing myself at my high school reunion, still the try-hard theater kid who loves the guitar boy who is nice to me but has absolutely no interest in me romantically, now returning a conquering hero, a successful television writer, creator and producer. It’s me at a party in LA with people who never really glanced in my direction but who now want to work with me. It’s me telling everyone I don’t care about awards while I swill my drink, careful not to spill on my gown at the Emmys after-party.

This is pure ego. This is monster shit. I hate these thoughts, and I’m ashamed of them. But why write something personal on the internet if you can’t share your secret shame? This is part of what hurts about the cancellation. I feel like a fucking idiot. How could I be so stupid? How could I let myself be so vain? So thirsty?

It is in this Tower moment that I begin to get notifications that I’ve been tagged in a post multiple times a day on instagram and Twitter. There are plenty of fans of my show. I have no idea how many people actually watched it (see: reasons for the WGA Strike of 2023), but there are lots of people who loved it, lots of people who are outraged that we’ve been canceled, who are starting hashtags to entice some other network into picking us up. I open my phone eagerly hoping for a hit from the validation crack pipe. My eyes light up at words like, “favorite writer,” “genius,” “best of the year.” Yes, I think, yes, okay, so maybe my show was canceled, but I can still have the satisfaction of validation from people who get it. Disney and FX will RUE THE DAY! my lizard brain cackles with the guttural chortle of a cartoon villain.

This is also the moment where I discover that there is another professional writer named Eliza Clark.

I’d had an inkling years ago that there might be another Eliza Clark when a credit appeared on my IMDB page for a show I’d never worked on. Some Eliza Clark had been a producer on a show called HOW TO LOOK GOOD NAKED CANADA. I’d never seen, written, or produced that show, but it gave me a little chuckle and I forgot about it. Whoever produced that show is not the Eliza Clark who has written a book called BOY PARTS that is taking the world by storm. No, because this Eliza Clark is a decade younger than I am. Twenty-fuckin'-five when her debut novel is published and blown up on the corner of TikTok called BookTok.

I’ve always dreamed of publishing a book. A novel maybe, or a book of essays. Have I written a novel? No. Have I written even part of a novel? Also no. One time I told my husband, “I might write a memoir,” and this man, this love of my life, this father of my children, looked me right in my vulnerable eyes and laughed, "About what?”

Eliza Clark is a decade younger than I am, publishing a novel that is being touted as genius all over the internet. And I’m stealing her valor. At first, I open these notifications and think, ugh, annoying, now I have to write to this internet stranger and tell them they’ve got the wrong Eliza. But there’s also a moment before I respond where I get a little hit of the validation meant for her, where I imagine myself as a beautiful, young, British writer, still under thirty, publishing her edgy debut novel to critical and reader acclaim. A few years later, she publishes her follow up novel, PENANCE, which the internet is saying is even better than her last book.

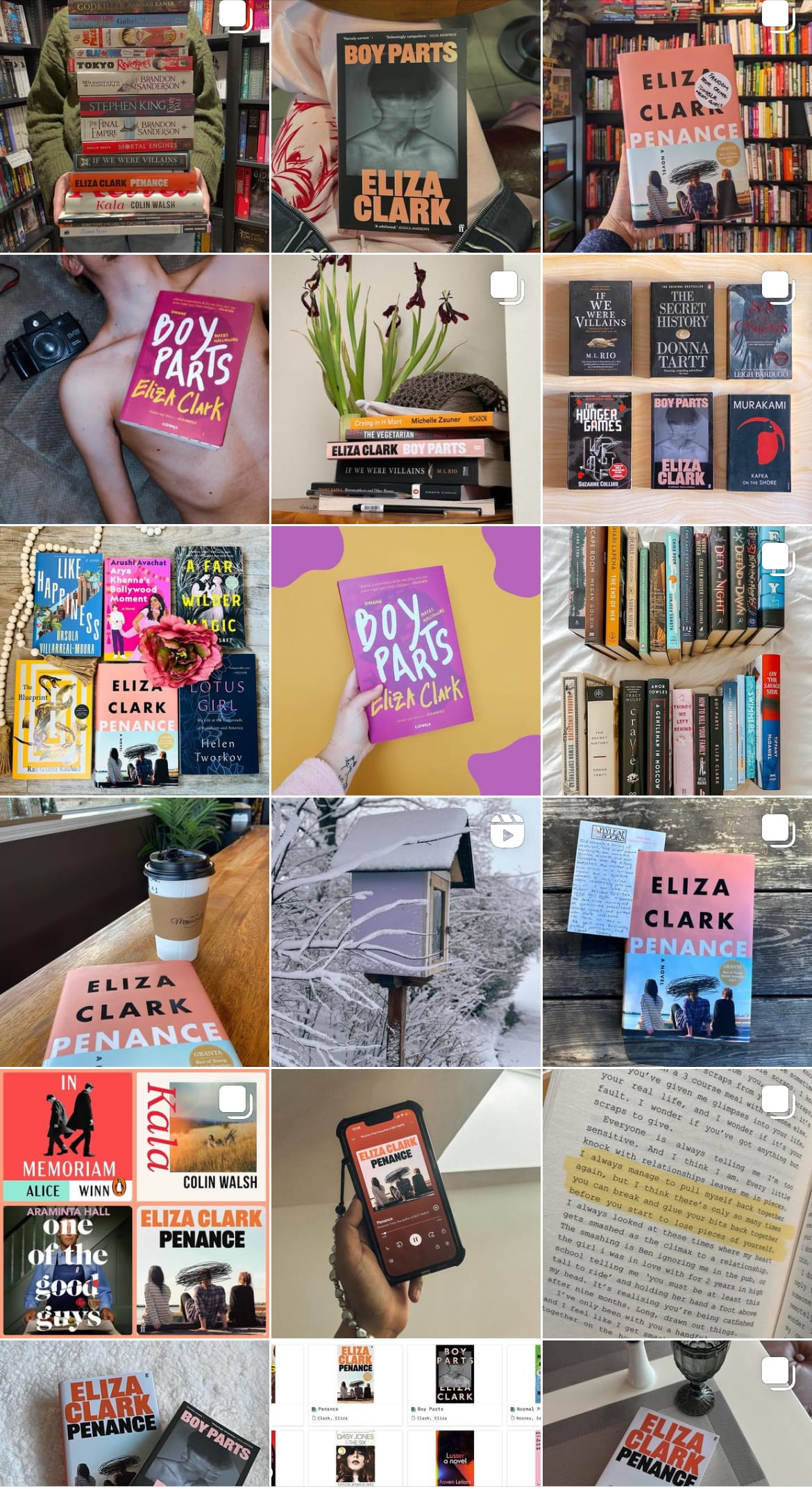

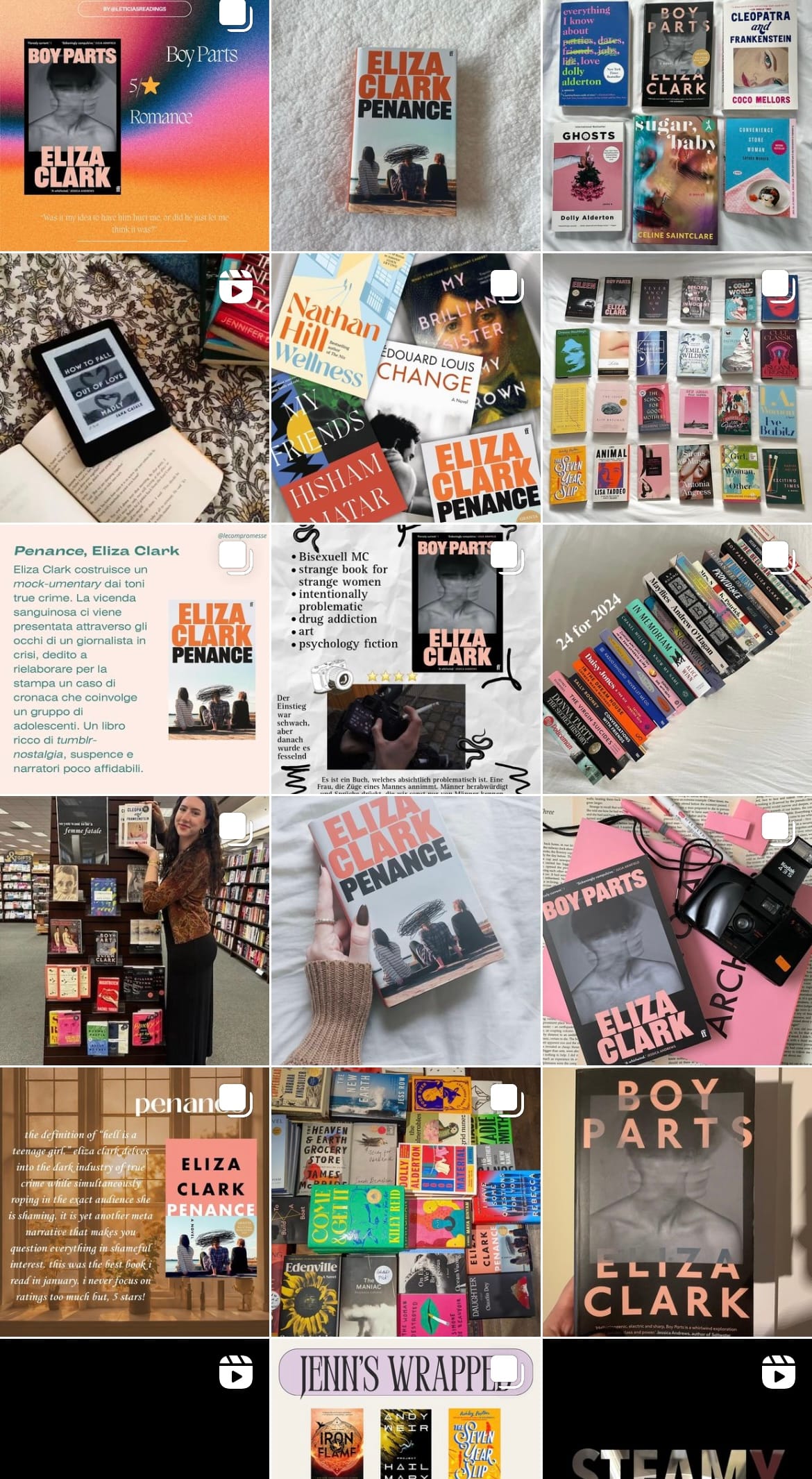

These are photos I have been tagged in. But sadly, I did not write a word of any of these books.

I got an agent at twenty-three years old and my first TV writing job at twenty-four. I was younger than everyone in most rooms I was in for a long, long time. And I loved it. In those days, my youth made me feel special and tingly. It also, frankly, lowered expectations. Nobody expected a twenty-four year old to know how to write or have good ideas, so I got to consistently exceed expectations. And for someone addicted to praise, lowered expectations is a great way to get that hit of validation over and over again.

Somewhere in the back of my head, of course, there was the thought: someday you will not be this young. But that was something I could worry about later, and hopefully if I kept up the pace, I could be young for whatever accomplishment I received. As long as I stayed ahead of the curve, I could always exceed expectations.

Friends, I am NOT PROUD OF THIS. I am spilling my guts to you, and it feels awful, honestly. But again, this is the internet, and we HAVE TO BE VULNERABLE by law. Truthfully, I'm relieved that I did not get to create and run a show at 25. Believe me, with the way I was thinking that would have been bad for me, bad for my liver, bad for my friends, bad for EVERYBODY. I’m grateful for the ways this business has broken me down, chewed me up a little, spit me out a different girl. I’m grateful for the lessons I’ve learned about what actually matters, and what it means to be an artist. I’m grateful to be almost forty and finally able to take a big step back from my ego and learn the difficult lesson that external validation will never fill my cup. I’ve grown up a lot in the last two decades, Thank Goddess.

I was still curious about this young woman taking the literary world by storm. Though I’ve seen her books everywhere — on bookshelves in the homes of people I admire, in the “Recommended” sections of book stores, on my social media — I had not read her work. Part of me was nervous. Her novel was called BOY PARTS and she was a British author. What if she was a gigantic TERF? What if this book with my name on it was transphobic? What if the people who were celebrating her (and tagging me) on the internet, were actually associating my name with bigotry?

Over Christmas, I read Naomi Klein’s Doppelgänger, a non-fiction exploration of truth, fantasy, conspiracy theories, and the internet. The seed for the book came from Klein being constantly confused for Naomi Wolf, a feminist turned anti-vax Trump supporter. Naomi Klein’s interest-turned-obsession with Naomi Wolf (at first, an attempt to separate herself and clear her own good name) became a story about our media culture’s polarization, about our new ability to choose our own facts, about our American conspiracy epidemic. Read this book, it’s amazing.

After I read Doppelgänger, I finally picked up Boy Parts and started to read. It felt good holding a book in my hands with "by Eliza Clark" on the cover. People who saw me reading it would say, “Wait—“ and I’d explain, no, I didn’t secretly write a novel. The book is decidedly not a transphobic screed. Instead it’s a dark and twisty fucked up story about an unlikeable female protagonist named Irina. It’s funny, the dialogue is searing and crackly, and the writing is taut and suspenseful. It’s right up my alley. I devoured it and moved on to Penance (also phenomenal).

So I reached out to Eliza and asked if she’d be willing to zoom with me about our strange connection. She agreed and we had a wide ranging conversation about unlikeable female characters, themes we keep returning to, the writing process, success at a young age, transphobia, our middle names, and so much more. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

[For the purposes of clarity in this interview, I am "Eli," and she is "Eliza"]

Eli Clark: This is so nice of you to do. Thank you so much.

Eliza Clark: I think it will be fun to to to do the international Eliza Summit.

Eli: We just need the Canadian author, Eliza Clark. Have you ever met her?

Eliza: No. I think she's a bit older than us, I’m gonna do a quick power Google. She's in her sixties. She was born in 1963. But she doesn't have a social media presence.

Eli: I think she did some work on a TV show called How To Look Good Naked: Canada. It was listed on my IMDB page for awhile. And I was like, I didn’t write that. I don’t know the first thing about how to look good naked in Canada. Or maybe there's a fourth Eliza Clark! Okay, I have so many questions for you. I love your writing, you’re so talented.

Eliza: Thank you.

Eli: Do you know anything about Tarot?

Eliza: A little bit. I suppose the most basic amount that people know.

Eli: Perfect. So The Star is about a lot of different things. It's about hope, renewal, creativity and inspiration. But I always think of it as that ineffable quality that makes you you. That's part of the fun of us talking to each other, writers with the same name. Now that I've read your work I realize we have a lot of things in common. Are there themes that you find yourself writing about again and again?

Eliza: I feel like I tend to come back to power. Power dynamics between people.

Eli: Do you know where that comes from?

Eliza: I don't know. I feel like just out of an interest in observing day to day hierarchies and how strange they are! It's something that I used to think a lot about in school when you find yourself at the bottom of a hierarchy, and you’re thinking, well, how did this happen? I remember being so very confused and frustrated by hierarchical thinking, and I guess that just kind of carried into my adult life. Those hierarchies don't often fade away. I’m interested in how they translate into people's personal relationships, or how they disappear when people are one on one. I just think it's sort of endlessly fascinating.

Eli: I’m fascinated by why we write what we write, the things you come back to again and again, even if you're doing it from a completely different angle. For some reason, I often write about the banality of evil. I was a child actor. When I was six, I was in this movie called Swing Kids where I had to say “Heil Hitler.” That was one of my 4 lines. My mother was like, If you're gonna say this, I need to explain to you what this means, why you're saying this in this movie and why you can't say it in any other context. So she kind of went, let me tell you all about The Holocaust. I learned a lot about all of that horror all at once, we went to a bunch of museums, we talked about it a lot, read books. It was overwhelming and horrifying and really scared me, but now it comes up in almost everything I write in some way. I’m interested in why regular people stand by when horrific things are happening.

Eliza: Yeah, it's something I think a lot about as well. Interestingly enough, I read Achan and Jerusalem when I was in University, and it had a really big impact on me in terms of the way I think about how people treat each other. Something that comes up a lot for me is the quotidian nature of violence. The banality of evil clicks into that quite a lot. The violence of day to day life.

Eli: I can feel that in your writing. You write complicated, complex, and unlikeable female characters. Can you talk about that a little bit, your interest in unlikeable women? And is there as much bullshit about that in the book world as there is in television? Are people constantly asking you to make your characters more likable?

Eliza: It depends. I haven't found that to be true so much in the corner of publishing that I'm in. I write in this sort of literary fiction zone. You can get away with it a little bit more. If anything, it's become a big selling point, this sort of feral girl/evil woman genre. But I think if I was in a more commercial space, that wouldn't be the case at all. I think I'd be having a lot more trouble with that sort of thing if I was writing an awful woman in a romance novel. That just wouldn't get published. I’ve felt it more as I’m doing more television work. I'm working on the TV adaptation of Boy Parts. It's in development.

Eli: Are you writing it?

Eliza: Yeah.

Eli: That’s great! Although, I was thinking I should write that, and then it could be, y'know, based on the novel by Eliza Clark, developed for television by Eliza Clark, produced by Eliza Clark and Eliza Clark…

Eliza: For the first episode we've had to tone the character down quite a lot just to to make it a bit more watchable. I think you can get away with it in a book a bit more than you can on screen.

Eli: But she's unlikeable in such a delicious way! Both your books have unreliable narrators. And they both seem to be asking, what is true? Does it even matter? Where does that come from?

Eliza: I'm interested in liars, and I think dramatic irony is just a really useful device. To be honest, I've begun to think, particularly around when I was writing Penance, that using the unreliable narrator again almost feels a little bit like a crutch for me. It's something I know I can default to. When I was in high school, I got introduced to this series of monologues written by Alan Bennett, the playwright, it was the series he did for the BBC called Talking Heads. They were just half hour monologues from one character performed directly at the camera. They were really revolutionary for me in terms of what you can do with storytelling. I was always inspired and interested in the lies that characters tell. The lies people choose to tell feel so much more revealing than the things they choose to tell the truth about. I've always been interested in the way stories change when they are filtered through the lenses of different peoples’ points of view. But in terms of it being maybe a little bit more of a crutch, there's just stuff you can kind of get away with a bit more when you're working with unreliable narrators. Your continuity can be a little bit wobbly. You can get away with lazier and worse prose, because you can just say, Well, I didn't write that. She wrote that.

Eli: I think that’s also the reason I like dialogue so much. It’s messy. It doesn’t have to be grammatically perfect. It's always much more interesting what someone doesn’t say, or how they skirt around the truth. How has the adaptation process been for you?

Eliza: I’ve basically been working on Boy Parts in some capacity kind of nonstop because of it. I started writing it in 2018, and I was editing it through 2019, then it got published in 2020, then we optioned it. The book came out in July of 2020, and we optioned it in August of 2020, and I commenced work on the adaptation in October of 2020. And then there's just been pretty much continuous work on it since. It's been like six solid years of Boy Parts. That the thing that has been the worst about it, just the sheer amount of time spent with one project. But it's mostly been an interesting learning experience. It's been really cool to rethink different aspects of the book. Because it's a first novel, it’s always going to feel like a very flawed piece of work to me. All I can see are its flaws now. Being able to sort of correct and go through and almost just tighten it up a bit, has felt quite nice in some ways.

Eli: I wrote a play called Edgewise in my senior year of college. I was twenty-one. It was my first good play, it got me lots of television jobs. It’s all about the quotidian nature of day to day violence and the banality of evil. I've tried to adapt it so many times as a film, but it’s so difficult. A different version of me wrote that play and that version of me was a little closer to being that young. That’s part of what's great about it, it's got three teenage characters who really feel like teenagers, because I had been one like five minutes before I wrote it. But it also has all these mistakes that I would just not make anymore. I’ve failed to adapt it many times. Finally my husband wrote an adaptation of it. I was like you do it, and it's beautiful. His adaptation is so good. It's basically the play, except he fixed all the things that I hated. But every time I had tried to adapt it, I was always just gutting it and ended up taking out everything that was good about it. Anyway, do you feel that way too? That you were a different person when you wrote your first novel?

Eliza: I often make this sort of flippant comment that they just shouldn't let you publish a book before you're 25. I was 25 when Boy Parts came out. I just feel like it should be illegal. If I recall correctly, most first time authors are 35 when their first book comes out. Below 35, you're usually categorized as a “Young Novelist.” And that opens up different award opportunities for you. Generally the big mainstream awards like the Booker prize or the Pulitzer in the US, I think the average person who lands on those lists tends to be more like 45 to 50. I guess “Young Novelist” gives an extra awards opportunity for people who probably aren't quite good enough to get on the main list.

Eli: But Boy Parts is so great! I can’t believe you were 25 when it came out. You’re a wunderkind!

Eliza: I was born in 94. I’ll be 30 in twelve days.

Eli: I'll be 39 in September. So are you Gen Z?

Eliza: I'm a cusp, Gen Zed Millennial. I'm the youngest Millennial.

Eli: I'm a geriatric Millennial.

Eliza: I’m the last qualifying year for the Millennials. The millennial crossover period. I’ve had more formative Internet experiences, but I also remember 9/11.

Eli: With that perspective, being 30… or almost 30, I'm so sorry.

Eliza: We've really got to cling to those last 12 days.

Eli: Enjoy it. Enjoy your twenties while you have them. But honestly, your thirties are better. Anyway, the adaptation process, I'm sure, is like sitting down with the younger version of yourself.

Eliza: There's a bunch of odd stuff that jumps out in Boy Parts to me, like there's a bit in the book where she’s given a bunch of money under sort of funny circumstances, which I've sort of retrofitted it in my head like, maybe she didn't actually receive that money, but it feels like such an expression of my financial anxiety at the time. The idea of having no money and then going to London and spending a bunch of money made me so physically sick at the time that I added in this free money, not thinking that maybe there's more conflict, and it's probably more interesting if she spends when she doesn't have the money. There are a bunch of little things like that, just like you were saying, the kind of mistakes that you wouldn't make if you wrote it again. There’s a really contrived bit where she goes and borrows a car from Will, a character who assaults her earlier in the book. It was adapted for the stage last year, and the writer who adapted it was like, I think maybe she should just borrow Eddie from Tesco's car, and I was like Oh, my God, of course she should! That makes so much more sense. That would have been so much quicker. That would have been 1,000 words of flab just immediately gone from the book!

Eli: Well, as someone who read the book very recently, I don’t see either of those moments as flaws! The way she deals with the assault feels very true to the character – she's acting tough, like it didn't happen. She's saying to herself "I wasn't raped..." though clearly what happened was an assault. And the money is also about her ambiguous morality. She's selling her photographs to someone who is kind of bankrolling her work, but she has no idea what this person is doing with the photos and she's choosing not to care.

Eliza: I suppose this is just an example of when you go back to your own work, things that might not necessarily be mistakes start to feel like mistakes, I guess. You almost generate a feeling like this must be wrong because I did it such a long time ago. So it can't be good.

Eli: Or maybe you just can feel the ways that you are better now. And so maybe it’s like, I wish the better version of me had written this, but it doesn't mean the version of you that wrote it was bad. Clearly, you’re extremely talented to have published a novel at twenty-five that was as celebrated as yours is! I know this because I receive I don't know how many tags and mentions a day from people who love your book. It's stolen valor.

Eliza: I felt so bad about that when I realized! It was just the crashing feeling of realizing you had created an administrative issue for someone else!

Eli: Ha, no! I liked it! My television show had been cancelled, and I was in this creative slump. And then every day I'd get all these notifications: you are the best! you are my favorite writer! I'd be like, you don't mean me, but I’ll take it.

Eliza: Sorry!

Eli: Don't be sorry! It’s like slipping into someone else’s life! I just feel bad that you’re not getting to see all of this praise. Most of the time, I'll say, actually, you’re looking for @fancyeliza, but sometimes I don’t because there are too many! So then I’ll just enjoy the praise. I'm gonna enjoy having my name on a book whether I wrote it or not.

Eliza: If it makes you feel better, I did also have a couple of people be like “Congratulations on Y: The Last Man.” I think that might have been my first sort of clue of like, Oh, shit! I probably should have used a pen name. I knew that you existed, but I thought you were an actress, and it makes sense finding out that you at least were an actress at one point. I don't know, you just don't really think about these things, I suppose, I feel like I had the thought for two seconds, should I have a pen name? My last name is pretty common, but then, you just don't really think about.

Eli: I don’t mind it! I just think we should fuck with people more! When I was falsely credited with How To Look Good Naked: Canada, I was like, oh, there's another writer named Eliza Clark, but she's not American, and then I conflated the two of you. But then it didn’t seem right because this other Eliza Clark is British. Then your books were doing so well, and it was exciting. I got to imagine myself in a life where I had written a novel.

Eliza: There must be something to be said about nominative determinism. Three Eliza Clarks that are all writers born at different points in the twentieth century. I don't know. I also have the other Eliza Clark on Good Reads. A bunch of her novels have been credited to me, and I think that's my job to fix, but I don't know how.

Eli: Have you read Doppelganger by Naomi Klein?

Eliza: No, I haven't but it's on my to-read list. People mix her up with Naomi Wolf, don't they?

Eli: Yes, but Naomi Wolf is crazy. It’s a bad association. I get mistaken for a celebrated author! Although I will admit, and this is my own bias, but I got worried when I first saw your book. I was like, a British author writing a book called Boy Parts. Oh, no! Is this going to be a TERF book? Any time I say that to a Brit, they're like, we're not all TERFS!

[NOTE: TERF stands for Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist. It also stands for Bigoted Fucking Asshole.]

Eliza: To be fair, our media climate has been so aggressively dominated by that. Most British people don't give a fuck, but it doesn't help that our entire media class seems to be very, very taken with this stuff. Actually I was harassed by a TERF when Boy Parts came out. I used to work for a women's Creative Writing magazine. And there was this psychotic account that tweeted at the magazine while I was running the Twitter. I tweeted to my personal account “everybody should block this account,” because it was masquerading as a women's writing club, but actually what it was doing was posting about transgender people every three minutes or something. It was demented. I think she's still going. To be fair, I did also say that I would, if given the opportunity, bare knuckle box every TERF…

Eli: So would I!

Eliza: She took that as a threat, but it isn't a threat. It's a sport. It's like I was saying I would play golf with each of them. Then we had a whole thing. The magazine that I used to work for periodically gets in trouble for not being trans exclusionary, and then they will bring me back up again, and I will get a new wave of stuff. But it's only happened a couple of times, I think maybe thrice. But it's unpleasant.

Eli: Sorry that you've been attacked. That’s awful. I, for whatever reason, have this real fear of British feminists.

Eliza: It's a very generational thing. You probably wouldn't need to worry about somebody around my age. But yeah, anybody who's ever written for even our left-leaning newspapers—

Eli: It’s overtaken feminism and liberal and progressive spaces. Anyway, we don't have to talk about this because we agree that we would both bare knuckle box every TERF.

Eliza: We'll get harassed again.

Eli: Fuck ‘em. So the Boy Parts dedication is “To my mom and dad. Please don’t read this.” Have they read it?

Eliza: No, they haven't. They've actually been quite good about it. They have read Penance.

Eli: My parents read everything I write. I can't stop them. My dad called me the other day and was like “I was just going through your journals from eighth grade.” I was like, “Dad! Don’t read my journals!” Did you and your parents have a conversation about it? How did you get them not to read it?

Eliza: I did the dedication, and they were like, is this a joke? And I was like, sort of but I also would prefer if you didn't read it. So they haven't read it. They were going to see the play adaptation, and then the actress that was playing Irena, Amy Kelly, got sick, so it got cancelled, so they still haven't seen Boy Parts in any form. I was super nervous obviously about all the sex stuff, the drug stuff. And then I was quite nervous about what they would think of Irena's parents, because I didn't want them to think that her parents had been based on them. I thought, Oh, no! What if they take it really personally? I think now they would probably know that the parents aren't based on them, but I still wouldn't like them to read all of the horrible sex and drug stuff.

Eli: I have actually written one play that was about my parents which I told them. They liked it, though. It was pretty flattering. I do always fear that they are going to think that things I’ve written are based on them, but they've they've gotten pretty good at knowing that I write fiction. I don’t know how I would feel about sexually explicit writing. I need to learn how to write sex without feeling squeamish. I'm an adult woman.

Eliza: I did feel quite squeamish while I was writing it to be honest. There was one day where I was writing one of the Eddie from Tesco sex scenes. I was living in Newcastle at the time, and there's a really nice old library called the the Lit and Phil, which is like the Literary and Philosophy Society Library. I was in the library writing, and then this school trip of, I think, 8 year olds came in, and I had this awful shit I was writing on my iPad. The screen was kind of tilted back so everybody could see it. I just remember tipping it forward and sliding down in my chair, and just sitting like that until the children had left the library.

Eli: I'll have to write sex scenes for TV and then we have to discuss the scene with actors, and we all have to read it and then talk about. It’s very hard! I don't know why I'm such a prude.

Eliza: I'm kind of a prude as well to be honest. Some of the things I write, particularly in Boy Parts, I will read back and be like “Eliza!”

Eli: I mean, you write it well! It's tantalizing, exciting, dark and cool. You write a lot about darkness. So do I. I don't think of myself as a very dark person, but I do like to write twisted shit. What is your interest in this darkness? Where does that come from?

Eliza: I'm quite morbid, my tastes are quite morbid. I've always kind of been like this. I liked horror when I was a kid. I've just always been quite interested in dark, nasty things. Like you, I'm pretty cuddly in real life. A lot of people, particularly after Boy Parts came out, when I was doing the odd bit of media stuff, people seemed really surprised by how pleasant I was. I think people are expecting me to be more like a Brett Eastern Ellis, kind of prickly, cold, maybe some kind of enfant terrible. I'm a lot more like, “Hello!”

Eli: I’ve had that happen too. Someone will read a script of mine, and then I go to a meeting with them, and they're like, “Wait, I'm so confused.” I just like to write about things that freak me out. That's when it feels good to me.

Eliza: I suppose it's just the stuff that's most interesting to me. There's just so much out there about normal stuff. And I'm pretty normal. And I don't know. I suppose I'm just more interested in extreme things. It’s just interesting, isn't it?

Eli: Totally. You’re also very funny. You have a good sense of humor. You write a lot of dark comedy. That’s my sweet spot too. Maybe it’s a thing: you get named Eliza Clark, you're a sweet girl, but you write horrific shit. That’s the Eliza Clark trope. Okay, be honest, do you enjoy writing?

Eliza: I do. Yeah, I think so. I've come to enjoy it in some ways less since it became my main source of income. It used to bring me more joy. It’s less that the joy is gone, and more that I need to find a different way to bring joy into it. It’s the double edged sword of monetizing your main hobby. This thing that I love to do, my big passion is now the thing that I get to do every day and that's amazing, but also now where do I go for fun? What do I do to relax now that this isn't relaxing anymore?

Eli: Do you have any other creative pursuits that are just hobbies?

Eliza: I cook a lot, I'm a failed artist. I went to art school. I’ve been trying to take up drawing more as a hobby to decompress a bit. But also because that was almost a professional pursuit for me, I get frustrated that it's not really good. I think when you are good enough at a creative thing to be professional at it, when you do another creative pursuit that you're not good enough to be professional at, it’s like why aren't I a professional standard artist? Why aren't I a professional pastry chef? This is so annoying.

Eli: I only recently started making art that I am not good at, that’s just for fun. It’s been helpful. Does cooking help you write?

Eliza: It does. It puts me into a really nice flow state. I enjoy having a Youtube video on about something really inane. Cooking for an hour is a good little break for me. Sometimes if I've been busy all day, and it gets to six or seven pm, I'm actually quite happy to just go and stand and cook for an hour. It's decompressing, and it's very relaxing. I suppose the main problem, particularly with baking is I don't have much of a sweet tooth, so it’s just kind of like “cool now there’s a cake here.” And now that's my responsibility to eat this cake over the next 3 days, and I don't want it.

Eli: I really wish that I had that problem. I’d be saying, oops, i just sat down and ate a whole cake. Did you write when you were a kid?

Eliza: I wrote fan fiction as a teenager. That was my main hobby.

Eli: What kind of fan fiction?

Eliza: Oh, I used to write it for loads of stuff. I wasn't particularly loyal to fandoms, I was just so much more invested in the thrill of being able to post a story online. Having other people read it and tell you that it's really good, even when it's not really good. So I'd work on a bunch of different stuff. I actually started writing for Harry Potter, which is now very cursed. I'm glad that I've sort of naturally gone off the series, so the JK Rowling incident hasn't felt quite as painful as it might have. It is kind of weird that the start of me taking writing a little bit more seriously is inextricably tied to this book series that has loads and loads of baggage now.

Eli: That’s true for a lot of people, I think. It’s a good series. She’s a good writer. She could have just kept her weird awful opinions to herself.

Eliza: Just could have not said any of that stuff.

Eli: Be a billionaire! Go be a billionaire! Why? Why?! Anyway!

Eliza: Yeah, I’d probably still have so much Harry Potter crap in my house if she hadn't done that. Maybe she's freed me from Millennial cringe. But yeah. I sort of bounced around fandoms. Mostly it was things that were big on Tumblr. I was using Tumblr a lot.

Eli: I love that. It was a way for you to publish and get feedback immediately.

Eliza: I quite quickly developed a mercenary attitude to my fan fiction as well. I would be deliberately identifying niches, like nobody's written anything for this pairing yet, so I'll do something for that. And then nobody's done this particular thing with these characters. So if I do that, people will read it. I quickly identified that humor was a big selling point as well, and that you could do a lot if you were funny, because a lot of people aren't funny. So if you're funny you can get away with a lot more stuff. Fandom communities have been really good places for me to develop my writing. I never had any issues with flame reviews, as we used to call them back in the day. I only ever had people being super nice to me, and all of the critical feedback that I got was always genuinely constructive. It was just a really good place to develop my writing and to concentrate on it. It helps so much with pacing, because there's there's so much stuff to focus on when you're first writing. Creating characters and world building, that’s much more interesting than working on your line level writing, and how to pace a story, and figuring out what is a 3,000 word idea? What idea is a 10,000 word idea? What's a long form idea? Fan fiction is so good for being able to work on that stuff while exploring ideas that I'd had for characters that I already liked, that already existed. It meant that I didn't get bogged down in character creation. People who are doing amateur storytelling, they'll make up some characters, and they'll get really, really into the characters. But then they never actually manage to transfer that over and write something. If you have a lot of experience in fan fiction, it makes it much easier to transfer all of those things you've learned to those original characters that you've come up with. It makes it feel much less daunting to start writing.

Eli: That's actually the reason I started this newsletter/blog/whatever this is. I make a living as a writer, which is amazing. That's all I ever wanted and I got it. But my husband is also a writer. We just went through a strike. It's stressful when your writing also pays for your children's dentistry and school. You have to find a way to love it again, and writing these essays every week, I’m able to enjoy the process. I was really not enjoying it for a little bit. It's nice to have to force myself, it's coming out on Monday no matter what. Just gotta do it. Can you tell me a little bit about your creative process? Where do you write?

Eliza: I write more successfully out of my house. It was a big issue over the pandemic. Because when I wrote Boy Parts, we lived in this city center, so I could just leave my house with my iPad and go and sit in a cafe. I would sit in the cafe for like six hours and write on my days off. It was super fun, and then I would go home and have my evening, and then sometimes I would go back the next day and do it again. That was very nice, very disciplined in a lot of ways. When I came to write Penance, my second book, there was added pressure. This first book is coming out, and I've got this deadline to meet, and then it’s March 2020. We're obviously thrust into a global pandemic. We'd quite recently move to London as well, so I'm in this new place. My partner and I are both working from home, living on top of each other as well, and I just couldn't write, I didn't write. I didn't touch anything until probably about October. I was finding myself oddly unable to do anything. When I was trying to work, I was really, really having to force myself because I couldn't. I couldn't go out and remove myself from the distractions of home. At home, there's all the practical distractions of I should clean, or I could start cooking. Or the more obvious distractions of, what if I just played the Playstation for six hours instead of doing any of this work? I was really disrupted by that, I think. So I was teaching myself how to make myself work at home, which has ended up being really useful. I do a lot more work at home now than I used to. I was previously super reliant on needing to physically go and sit somewhere. I feel like I could actually do with a bit more of a process. I'm led by when I want to work or deadlines.

Eli: Where do your ideas come from?

Eliza: I get a lot of ideas from other media– nonfiction media like podcasts, nonfiction books and odd articles that I've read here and there. I quite like just stealing an idea pretty much whole cloth from a film or a TV show that I like, and putting my own spin on it. The most important thing you can learn as a writer is to steal things and then disguise them appropriately so people don't realize that you've stolen it. I'm lucky, I don't have a lot of trouble coming up with ideas.

Eli: When did you have the idea for Penance?

Eliza: That was a bit of a funny process. I didn't really feel like I organically had the idea. I knew that I had to write a second book, because I'd signed a two book deal. It was less like I had the idea, and more that I had to come up with it. I was trying to think of something that I knew would be detailed and multi-layered enough and contain enough different things that it could sustain my interest for a whole novel. Also I wanted to do something different from Boy Parts so people didn't call me a hack. We're in this period with publishing where a lot of young writers are getting these two book deals. The first book will do well, because somebody spent three years writing it. And then the second book will be something that has quite obviously been written in like one to two years, and it's just not as good. And it's really similar to the first book as well. I think that's an industry problem, not a writer problem. People need more time to come up with a second novel, because the second novel is famously so much more difficult than a first novel. You've got this much more difficult book, but you're contractually obliged to write it in two years. I knew that I wanted to do something different, and I wanted to do something way more ambitious. Essentially so people would take me seriously. I knew that Boy Parts is a book that could quite easily not be taken seriously by a lot of people. And I was quite lucky, because I moved publishers. I was with a small press in the UK originally, and then I moved to Faber and Faber in early 2021. I basically bought myself an extra year. Penance would have been terrible without that extra year. It gave me time to completely rethink the whole thing, to do a lot more research and think a lot more about the way that non fiction books are structured. It was almost this gradual layering of ideas. The story is based on a couple of real life cases. There was one in the States, the murder of Shanda Sharer in the mid nineties, and then one in the UK, which is the murder of Suzanne Capper, which also happened in the early nineties. Those were the stories that I was pulling from the most. Then, you need a setting, and my partner is from this little seaside town called Scarborough on the north east coast. He told me an anecdote about the town, he referred very casually to “the donkey strangling incident in Scarborough,” and I was like the what?! And then he told me about this incident, which I put in Penance pretty much whole cloth. Somebody was going around trying to strangle donkeys with a rope, and none of the donkeys died. But but somebody was trying to strangle donkeys and they don't know who did it. They never caught the person that did it.

Eli: Some psychopath who was very bad at strangling donkeys.

Eliza: I know. Maybe they're just super hard to strangle? Very thick necks, I guess. But he said that, and I thought, Oh, this would be like the perfect setting for this teenage girl murder idea. I have to put it in a seaside town in the UK, because pretty much all seaside towns in the UK are like that. Some of them are a lot more bougie, and some of them are a lot more deprived. But there's always this kind of rundown, faded glamour. They were these beautiful, Victorian holiday destinations that have either fall into a bit of disrepair, or they’ve fallen into complete disrepair. I just think it's such an interesting setting. And then it was just about reading more true crime and working out how to focus it. I always knew that I wanted to do some town history as soon as I had the idea for the setting, and then the narration came a lot later in the process. I read In Cold Blood in the autumn of 2021, and then read a bunch about Truman Capote. I was so interested in the amount of fabrication that went into that book, and the way he torched his entire social life because he couldn't stop writing about people in the press.

Eli: Are you writing something now?

Eliza: I am. I've got a short story collection that's coming out in the UK in November of this year. I think it's coming out simultaneously in the US, but I'm not sure. It's called She's Always Hungry. I'm very proud of it. I'm really excited to get it out there. In the UK, there’s almost this foregone conclusion that nobody's going to buy a short story collection except people who are really into short story collections. So it's low pressure. And I'm just very excited to have this low pressure/not particularly commercial thing come out that I can just enjoy at the end of the year. And then I am working on a third novel as well, which is in more of a speculative space. But I'm not super far along into that.

Eli: Will Penance have a television adaptation?

Eliza: It's been optioned. It's gone to a writer friend of mine, Juno Dawson. She’s super super cool. She's actually the writer of one of the most banned books in the US at the moment. She wrote This Book Is Gay. It’s been heavily persecuted by the Christian right in American school libraries. It's a sex education book for kids, and it's really useful, and everybody loves it.

Eli: It's LGBTQ inclusive?

Eliza: It's a queer sex education book aimed at teenagers. And it's really cool. She's a great writer. She's done a lot of work for the LGBT community. She's fantastic. She's also done a really cool adult book series called Her Majesty's Royal Coven, which is a pun on the UK version of the the IRS, called the HMRC. She has the option for Penance and she's working with Altitude Pictures developing that. What a joy to be able to hand it off to someone that I trust.

Eli: Well, I could talk to you all day. It's so nice to actually get to meet you.

Eliza: Yeah, it is really nice. Oh, I had a question for you actually! What is your middle name?

Eli: Atkins. What's yours?

Eliza: It's Alice. So we have the same middle initial as well! I thought this was going to be my big fix. If I ever did any American TV work, it's like fine, I’ll just be like Eliza A Clark!

Eli: You can have the “A!” That’s crazy. There's something going on here. Something witchy. It would be amazing if my middle name was Alice, though. Well, thank you, Eliza.

Eliza: Okay. Bye, Eliza.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Boy Parts by Eliza Clark

Penance by Eliza Clark

She's Always Hungry by Eliza Clark

Doppelganger: A Trip Into The Mirror World by Naomi Klein

This Book Is Gay by Juno Dawson