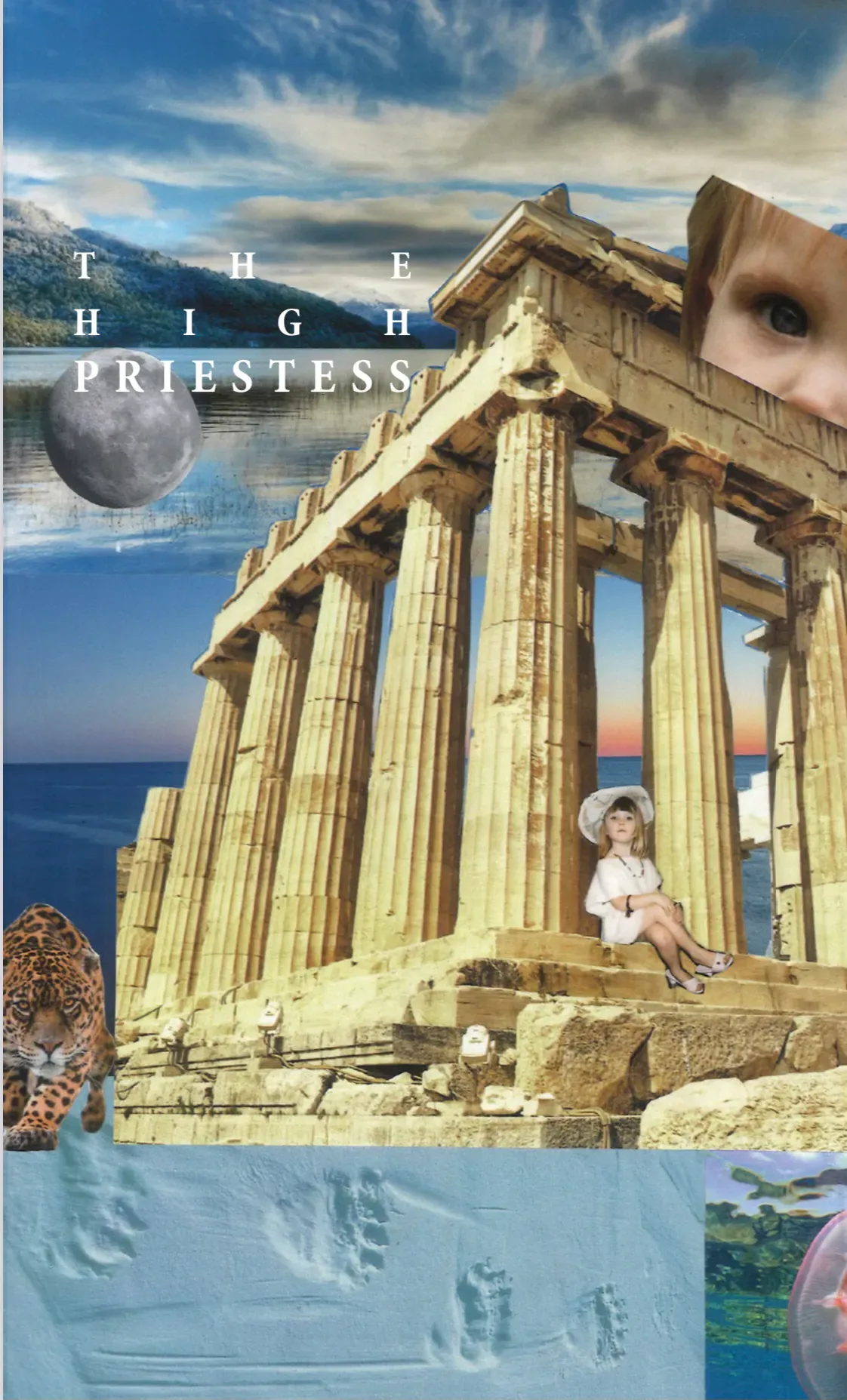

The High Priestess

“Stay still,” I hear myself say, “I’m looking for your witch’s mark.” “My what?” she asks, suddenly still, at attention, all five years of her have led to this moment and she is hanging on every word.

I am brushing my daughter’s hair after a bath. It is long, dripping on the wood floor, leaving puddles. She hates to have it brushed. There is nothing worse for a child than standing still. Every time I brush her hair, I remember the feeling I had at five, feeling paralyzed as someone bigger than me ran a comb through my tangles.

My daughter is squealing, squirming, trying to wriggle out from under the brush. She hates it, I’m hurting her, she hates me, she tells me again and again until I release her. But tonight I have promised myself I will deal with her mane. She used to tell us when she was small that she wanted hair as long as Rapunzel’s. When she would meet another girl at a playground or in a grocery store, at school or a party, she would pull me aside to ask me: Is my hair longer or is her’s? I always tried to discourage the competition, different people have different lengths of hair, but my daughter’s hair is her superpower, her femininity, longer than Rapunzel’s, longer than any other kid at the playground. So sometimes I let her win. “Yours,” I tell her, “Yours is the longest hair in the neighborhood.”

Most of the time, I forget to brush it, or I lose the fight and surrender. I hated having my hair brushed, so does she, who cares if there are mats and tangles? She’ll survive. Of course this is another way I punish myself — motherhood often feels like pinging between different ways you perceive that you have failed your child. I am the mother of the child with tangled hair. Why doesn’t she cut it, the public wonders. Why doesn’t the mother brush it?

Tonight I will brush her hair. She will go to bed without it dripping, wearing clean, warm pajamas and smelling like baby shampoo. She squirms, she screams, but I am relentless. She is miserable in the face of my maternal determination. And then, I hear myself, before I have time to think about what I am saying.

“Stop squirming,” I hear myself say, “I’m looking for your witch’s mark.”

“My what?” she asks, suddenly still, at attention, all five years of her have led to this moment and she is hanging on every word.

I am riffing now, improvising. A witch’s mark, I tell her, is something only your mother can see (smart, of course, so she doesn’t go asking some other grown up only to discover that her mother is a liar). A witch’s mark is special, it means you are destined for greatness, even magical abilities, powers. She is rapt with attention, her breathing steadies, and it is no longer difficult to pull the teeth of this hideous beglittered brush through her hair.

She waits for me to find it and of course I do. There, on her head, the invisible mark that only I can see. “What is my power?” she asks, breathless. I tell her I don’t know. That isn’t something I can see. She will have to discover it in time. She is hoping for x-ray vision or flight, the ability to create objects out of thin air. But I try to temper her expectations. Perhaps her witch’s mark is music or kindness. She brushes that off. No one wants their super power to be kindness.

She is an anxious child, five when the coronavirus stops time and upends her life. She starts asking me daily if I am close to death, or panicking when I leave the house, even for a moment, even just to go grab something down the street or in my car. She becomes convinced that her witch’s mark is something she can lose if she doesn’t follow rules. I do not remember telling her that, but I will not rule it out in a moment of duress, a desperate attempt to bring peace to our claustrophobic quarantined home.

I am washing an apple in the kitchen sink, and she slinks into the room. “Do I still have my witch’s mark?” I turn to her, her cheeks red with some unspoken shame. “Why?” I ask her. “I bit Toby” or “I threw my toy” or another confession. “Did you say you’re sorry?” I ask. “Yes.”

“Your witch’s mark is still there. Of course it is.”

Sometimes she asks me to check. I try not to become embroiled in her compulsive rituals. I was a relentlessly ritualistic child, developing all kinds of practices to deal with my anxiety. In fifth grade, I call my parents into my room multiple times a night to confess various sins — In kindergarten, I told Tracy I didn’t like her sneakers or Three years ago I told Spencer he couldn’t play with me.

I don’t want this to be a part of her life, this constant need for external reassurance. The absolution of perceived sin through confession to an authority figure. I don’t want her to feel this much shame and worry when she is still this small and magical.

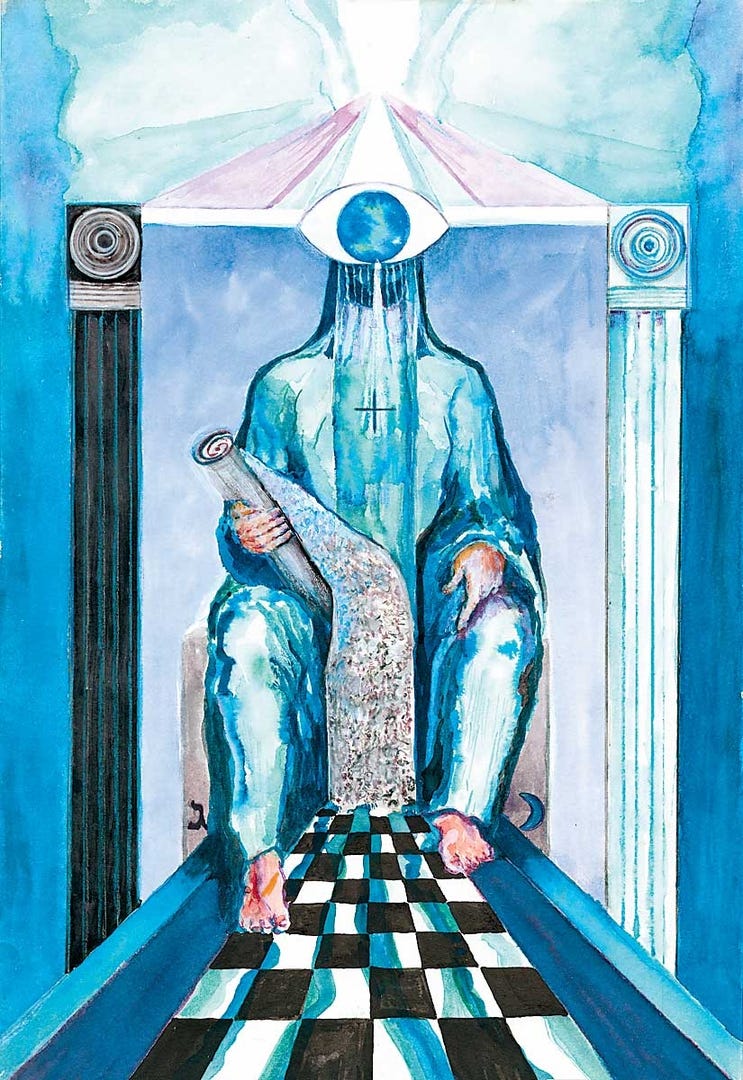

I explain that her witch’s mark is permanent. It will never leave her unless she stops believing in it. That is the only circumstance in which it can fade. My witch’s mark, for example, has been stronger in different parts of my life, and barely there at others. I try to help her understand it as intuition, the small voice inside her own head who knows what she must do next.

Now she’s seven, and her witch’s mark is strong and powerful. She believes that it allows her to speak to me telepathically. She hates bedtime, hates to be alone (both of my pandemic children do), and after I’ve done the many requisite check-ins down and up the stairs, I will sometimes offer a chance for us to speak to each other through our witch’s marks. This way I can stay downstairs watching Vanderpump Rules and she can still commune with me, and hear me reply.

Only once has that backfired, on a particularly hard night, where she refuses to go to sleep. She’s terrified, she says, of her closet, of her room, of our house, of everything. And in spite of every reassurance, she is unshakeable in her inability to settle and her unreasonable insistence that everything in her room is trying to kill her. I tell her, after fifteen journeys up and down the stairs, that she doesn’t have to sleep but she must stay in her bed. She can talk to me through our witch’s marks and I will respond.

After a half hour or so she is asleep. But the next morning she apologizes to me. Turns out she was telling me again and again through our witch’s marks: I hate you, I hate you, I hate you.

She’s about to turn eight and she has started to say things like, “REDACTED taught me how to make boys like you.” I am livid with REDACTED (who is only seven, and also a child of the patriarchal world in which we live), but I try to sort my thoughts out the best I can. “Why do you have to make boys like you? What do they have to do to make you like them?” I say, proud of myself.

But, of course, I remember what it was like to be eight. At eight years old the boy I loved barely knew who I was, but he was beautiful. Blond and blue-eyed (I lived in Connecticut) and named Tripp (because he was the third of some familial dynasty). What did I like about him, besides his hair? His pretty face? His khakis? And did he know I existed? I can’t remember. Nothing came of it.

My daughter is beautiful, and I tell her this, but I temper it with many other things. She is funny, she is kind, she is smart. “It doesn’t matter what you look like, but you are beautiful.” Lately she smiles and says “I know.” What a beautiful thing to know that you are beautiful. That’s something I have never known, unfortunately, even though I think I’m alright. Pretty, even sometimes beautiful. Every time I see myself in retrospect I can see beauty. I can see how my eyes are reflected in the light of the water, how my hair cascades around my face, how the wind blows through it, how the sunlight plays across my skin. I can see a picture of a self from long ago and think, “Look at her, she’s beautiful.” I can also remember how I felt when I took the picture: my face too round, my body too big. It’s painful to remember hating myself then, when I can see only now in the third person just how beautiful I was. I know that this feeling comes to us all, because the world wears us down. But for now, I delight in the moments when I say to my little girl, “It doesn’t matter what you look like, but you are beautiful,” and she smiles and says, “I know.”

She is nine, and I am putting her to bed. “I have discovered my superpower,” she says. “Tell me,” I prompt her.

“I can read my own mind.”

I am about to correct her, to question her wording, but I stop myself. This is the only superpower worth anything. This is the superpower I’ve been searching for my entire life. She can read her own mind. Maybe one day I’ll be able to say the same thing.

Book recommendations!!!

I cannot say enough good things about Listening In The Dark: Women Reclaiming The Power of Intuition, an anthology edited by my brilliant friend, Amber Tamblyn, with essays from Meredith Talusan, Huma Abedin, Amy Poehler, Congresswoman Ayanna Presley, Jia Tolentino, Lidia Yuknavitch, Amber herself, and so many more. Amber also has a Substack by the same name — Listening In The Dark — which I highly recommend if you’re trying to get in tune with your intuition and/or enjoy great writing.

The Way of Integrity: Finding the Path to Your True Self by Martha Beck. This one is a self-help book, so know that going in. But I found it very useful as a lifelong people pleaser and former child actor. A road map to living your most authentic life.

Your High Priestess playlist (this one is fun to write and/or meditate to – lots of moody, intuitive music):

Let me know what songs you would add this playlist in the comments!