The Chariot

Aging is a sloughing off of fucks given. Each birthday, I shed a new layer of fucks, until eventually, I’ll care only about joy, pleasure, and freedom.

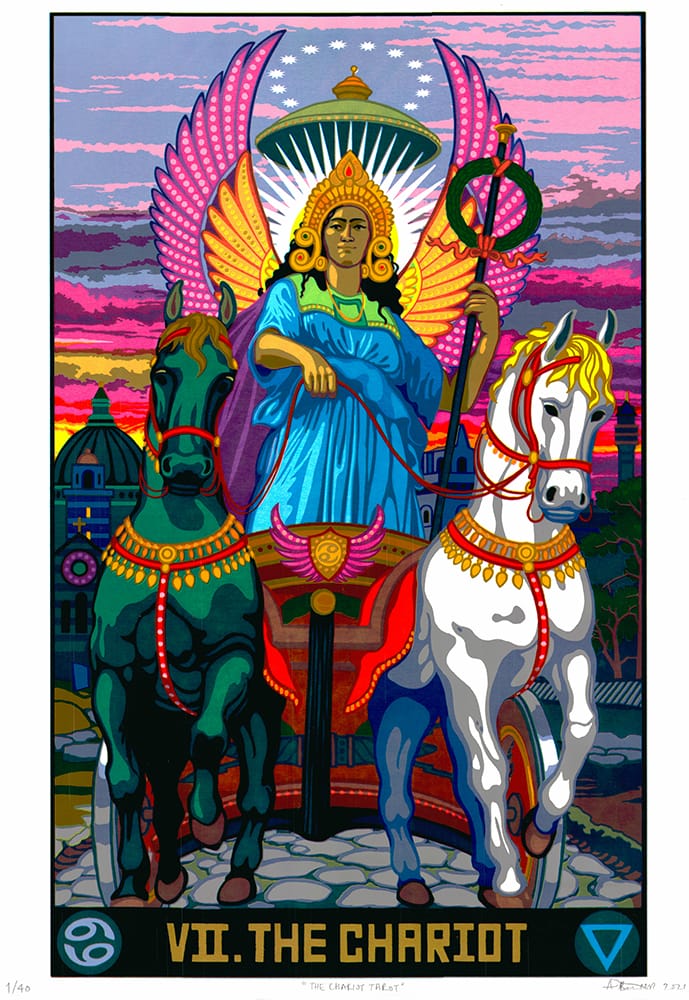

The Chariot is a card about victory through determination and force of will. It’s about forward movement, momentum, action. In many Tarot decks, a charioteer sits atop his chariot pulled by two horses or sphinxes or other beasts, but he doesn’t hold the reins. He is relaxed and powerful, able to control the forward motion of the vehicle with the force of his will. When you get this card in a reading, you’re being encouraged to charge forward, in control of your destiny.

Here's something I miss about drinking: the release. I loved the shift from sobriety to not, the swirl and clink of ice in a glass, the glug glug of the pour, the biting taste, the burn in the back of my throat, the warmth in my belly. I do not miss the fuzzy tongue, the drumbeat in my skull, the dehydration, shame, and regret. But I do miss that brief moment of freefall, the white flag of surrender to my brain that declared it is time to power down, to let go, to relax. For a thousand reasons, my brain is a rubber band ball, all tension no release. My brain is a chariot that I drive with the reins wrapped tightly in my fists, knuckles bleeding, fists bruising from the tension of the ropes. I'm a relentless perfectionist, with an active and cruel inner critic. Booze was the quickest and most direct path to pleasure (albeit brief). Booze was a signal to my brain that it was okay to let go.

Like many little girls in the 1990s, I was enrolled in dance classes at an early age to be taught the basics of ballet, jazz, and tap. It became quickly apparent that I was not a naturally gifted dancer, nor was I even a basically gifted dancer, or really a dancer at all. I remember first and second position, I remember jazz hands, I remember sparkling outfits and tutus, and I remember a big smile on my face as I somehow managed to end up on the opposite side of the stage from everybody else an impressive number of times no matter how much instruction I received.

1989. Age 4. Fucking KILLING IT as a dancer. I'm (naturally) the first one on stage.

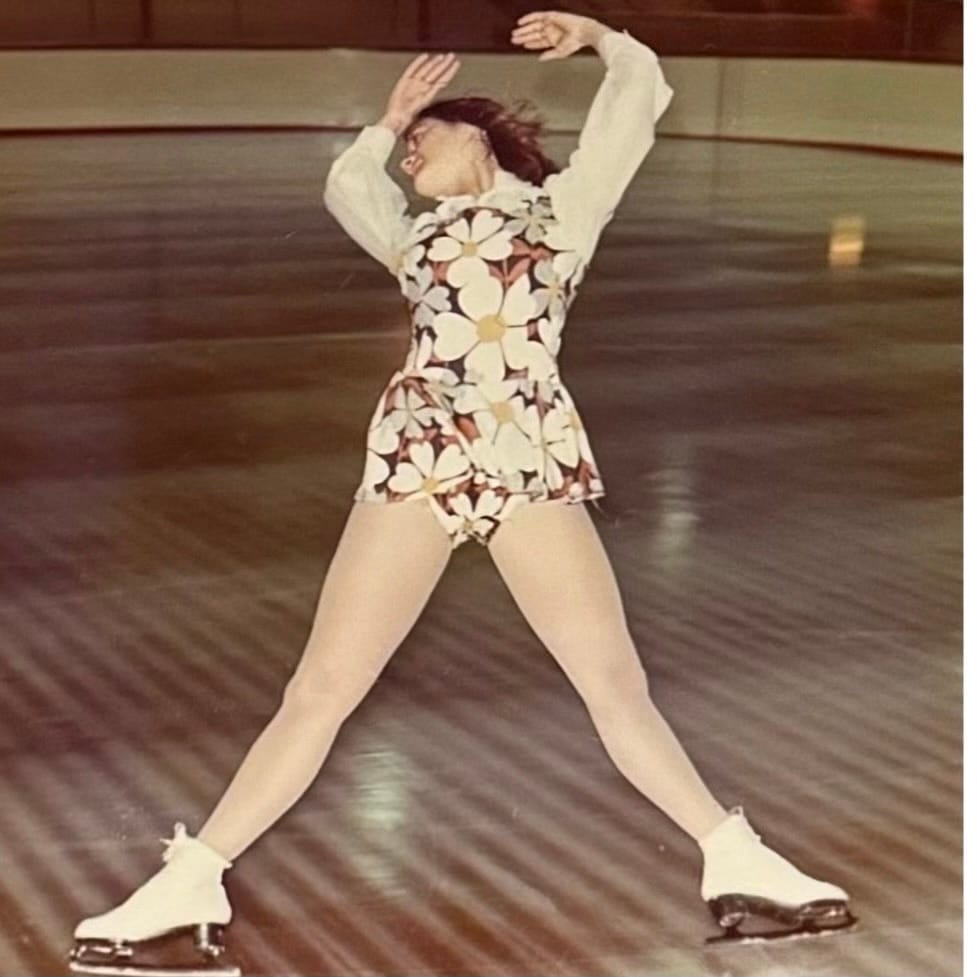

I enjoy doing things I’m naturally good at, always have. I’m not a particularly resilient person. It’s not that I’m averse to hard work. I’m happy to put in the hours, but I like those hours to be spent on something for which I have an adequate baseline. I don’t know where this fragility came from. My mother is a professional athlete. She started figure skating at the over-the-hill age of twelve, was told repeatedly that she’d never make it, and boy, did she show them.

My mother is the embodiment of The Chariot. She would spend hours practicing the same edge over and over again until she perfected it. Though she was told by many coaches that she had started way too late to make something of herself, she earned two gold medals (the highest achievement figure skating offers, with only the Olympics above it in prestige). Speaking of which, my mother has coached multiple Olympians. If you tell my mother she can’t do something, she’ll do everything in her power to make it happen. If you tell me I can’t do something, I’ll agree and take a nap.

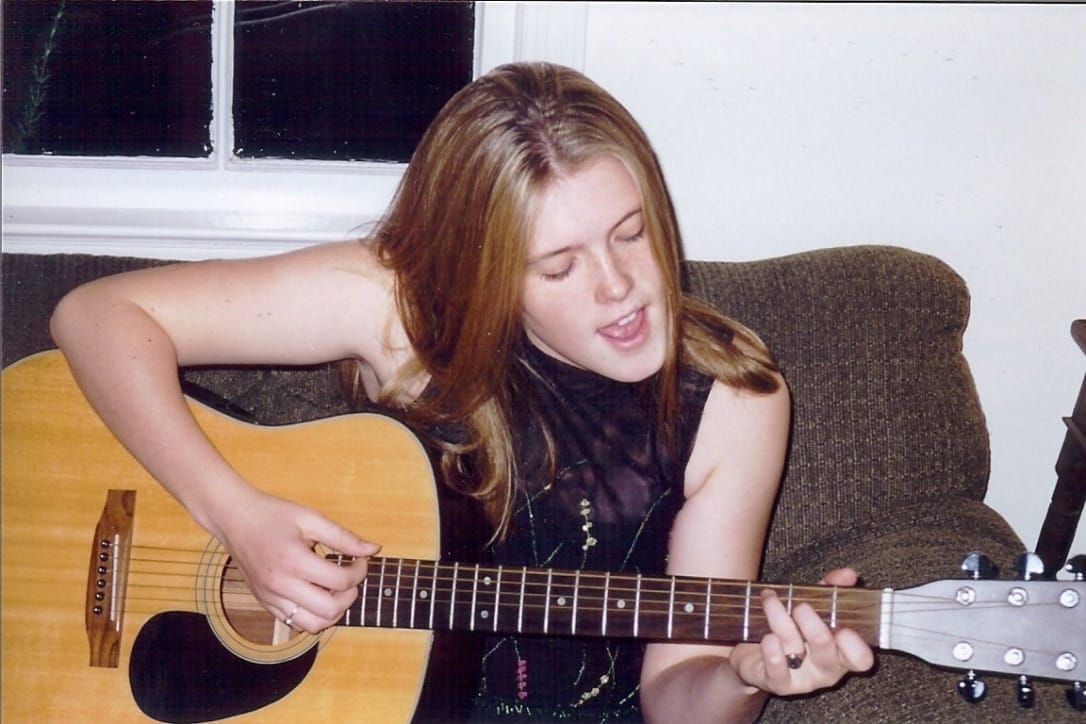

Perhaps all the negativity directed at my mother caused her to overcorrect her praise for my brother and me. When we were good at something, my parents heaped praise on us, oftentimes unjustified. For example, I started playing the guitar as a pre-teen, but had very little patience for basics. Instead, I wanted to learn just enough to write moody songs about teen pregnancy, which is exactly what I did. My mother fed the beast by telling me the songs were amazing, and paid for a few hours in a local recording studio where I could “lay down my tracks.” Recently in a bout of nostalgia and at the urging of my nine year old, I asked my mother to send me my old demos. She boxed up the CDs and sent them over. Zack had to buy a CD converter to get the songs onto the computer, but he did so dutifully and with morbid curiosity. I had hyped my album, remembering my lyrical prowess as pretty darn good for an eighth grader.

Friends, the songs were bad. They were angsty Jewel rip-offs, except Jewel lived in her car and I lived in my parents’ house in Connecticut. I listened with my hands over my eyes in horror, as if somehow the songs might come to life and chase me around my house.

One holiday break from college, I was driving somewhere with my father and brother and we passed a group of middle school girls playing softball. Wistfully, I turned to my family and said, “Remember how good I was at softball?” My brother burst out laughing, practically in tears. “What?” I asked sharply, stunned. My brother informed me that in spite of my parents’ encouragement, I was not, in fact, good at softball. “I was one of the best on my team!” I shot back. Apparently, though technically true, that fact meant very little, as my team was very, very bad.

The point is: my parents were encouraging. They were our biggest fans. They worked hard so we could pursue our various dreams (no matter how absurd), and if we liked something enough, they lied and told us we were good at it until it came true (or we eventually found something else). Recently, my parents were in town, and my mother listened in as my daughter took a piano lesson. After watching my daughter play “Mary Had A Little Lamb” my mother burst into my room seconds away from getting Carnegie Hall on the horn, “She’s amazing! I couldn’t even believe it! She’s a natural! She didn’t even look down!”

I know that parenting style is no longer in fashion. We’re supposed to praise our children’s hard work rather than the final product. We’re supposed to look our kids in the eye and say, “Are you proud of yourself?” instead of telling them we’re proud of them, lest they grow addicted to external validation. But listen, my parents were great, and I appreciate their white lies. If I had known how bad my songs were, I never would have recorded them, and then what would my friends and I have quoted in our high school yearbook? (Yes, my friends and I all quoted “The Drinking Song” by lyrical genius and precursor to Taylor Swift, Eliza Clark, on our senior page — “Let’s drink to friendship, it’s the only thing that matters anyway.”)

Unlike my mother, I was not out to prove anything. If I felt even the whiff of shame or possible embarrassment, I’d run screaming from an activity. In high school, my physics teacher referred to the four girls in the class as “The Spice Girls,” which was meant to be belittling, because we were bad at physics. There may have been another girl in the class who was incensed by the nickname, who worked hard to prove him wrong and went on to win a Nobel Prize. I, however, agreed with sexist Mr. Whatever His Name Was, and frankly, the Spice Girls slapped. As long as I got to be Baby Spice, and could just keep my head down and pass the stupid class, I didn’t care. There was no world where I was becoming a physicist. I didn’t ask or answer another question the rest of the year, but I passed the class, and promptly forgot every single thing I’d ever learned about physics.

Which brings me back to dance. Dance, like math and the broader sciences (sad to say, I'll never be a woman in STEM), belonged firmly in the “I’m bad at this” category. I could make my way through middle school and high school dances, which involved only two kinds of dance: slow swaying back and forth with your arms around a boys’ neck, or “grinding” where a boy rubbed his semi-hard boner against your ass and you bobbed up and down on your knees and pretended to like it. Grinding was as easy as a sex crime on the subway. And the point was not how good you were at dancing, the point was how good you looked in a tube dress.

As I got older, I shied away from dancing publicly. I never went clubbing, for example. The only time I ever went to a “club” in college, I was there to see Dar Williams play an acoustic set (the audience sat cross-legged on the beer-sticky floor). At weddings, I relied on little-used air instruments like the violin, cello, or flute and hoped that people would find that funny enough to pass as dancing. It wasn’t funny, but it was mildly amusing which will suffice at a wedding.

So it’s a little difficult to understand why, after years of solidly defining myself as a non-dancer, I suddenly felt a call to dance. Covid had something to do with it. The whole world came to a grinding halt, and I was stir crazy. There was something restless inside of me that needed to move. My friend, Chantal Robson, is an incredible choreographer. She has always been one of the hardest working people I know and she was suddenly stuck at home stifling her gift. I asked her if she’d be willing to teach me and a couple of my friends a dance routine over zoom. Remember early Covid? When we were all making sourdough bread, drinking our faces off, and learning new skills? Dancing was my sourdough.

There was something safe about being in my own bedroom and only showing up on other people’s screens in a tiny box. Chantal is a kind and generous person, and she’s a great teacher. She never used complicated dance terminology. Instead she’d say things like, “You’re a broken doll,” or “Pull the cord on the lawnmower.” She was encouraging and her choreography was hard enough to make us feel accomplished without making us feel stupid.

When I went off to Toronto to shoot Y: The Last Man at the height of Covid, it became apparent that our cast needed something we could safely do together that was just for fun. Every Saturday for most of those ten months, Chantal and the cast and I (with occasional drop ins from members of the crew, producers, and whoever was up for it) would gather on zoom to learn choreographed dance routines. You might think to yourself, how did you go from being embarrassed to dance publicly to suddenly willing to dance with gorgeous actresses? I don’t know the answer to that question, honestly. I think it was the power of zoom, the fact that I felt we all really needed it, and how fun this group of women were. It was one of the only things we could do for fun during a time when everything was closed.

To be clear, I still made near constant fun of my dancing, to protect myself from any vulnerability. It was important that I made sure everyone knew I was in on the joke. I would constantly talk about dance competitions or “going pro,” which is just another version of air instruments. I wasn’t ready to fully commit to how badly I wanted to get better or how much completely earnest fun I was having. I kept my desire at arm’s length.

On set, we’d sometimes do our routines between set-ups. We would frequently make fellow cast members Ben Schnetzer and Elliot Fletcher, as well as Amber's husband, David Cross, my husband, guest stars, and our entire camera team watch us dance (they were invited to join the dancing, but they all opted out, though I’d pay millions of dollars to see David Cross in a dance class – and that is a standing offer, David). Even though Elliot never took the class, he was the best Dance Dad, aping the moves from the sidelines and cheering us on (We love you Elliot, thank you for believing in us). I’m pretty sure like any great Dance Dad, he could have subbed in at a moment’s notice if anyone broke an ankle on competition day.

Eventually, production ended and Chantal went back to in-person work with real dancers. I thought my dance career was over, which was fine. I had convinced myself this was something I did as a bonding exercise with my cast, something that was fun and silly, a fun memory from a weird and isolating time in the frozen North.

Then, my sister-in-law, Maurissa, invited me to an “all levels” dance class around the corner from my house. Maurissa is a for-real dancer. She was a teenaged pop star in a group called Pretty in Pink. Maurissa is gorgeous and cool. The first time I met her I dropped all my silverware on the floor of the restaurant, okay? Taking a dance class with her was probably the scariest thing I could have taken on, but I was newly sober, which made the idea of doing something I was scared of weirdly appealing. What could the non-drinking me accomplish?

And this is how I met Melissa Schade. Melissa might be the coolest person, um, in the world? I don’t know if there’s a way of quantifying that, but if there is, she should be tested and given her award. Melissa is a dancer and choreographer, and on Sundays, she teaches an all-levels dance class that is a mix of really fucking great dancers, some people who must have danced when they were children, a handful of non-dancers who are naturally sexy people who have moved their hips before in their lifetimes, and me.

I’ve pitched to John Landgraf, probably the smartest executive in all of Hollywood (he’s also a lovely, smart, kind man who loves artists, but he is intimidating), and still, this all-levels dance class is the single most intimidating thing I’ve ever participated in. That might have something to do with the story I’ve told myself about myself my whole life. It’s really hard to change a narrative you’ve been brainwashing yourself with since birth.

Without hyperbole, this dance class has completely changed my conception of myself. It has increased my resilience, helped me get in touch with my body, made me feel (gasp) sexy, and really helped me get over myself. Melissa mixes dance terminology with non-dancer analogies. I now know what “relevé” means (and even sort of how to do one), but I also understand what Melissa means when she says to “be a creature” or “tee-tee.” Melissa constantly tells us not to watch ourselves in the mirror, especially if we’re doing something “sexy.” She’s picked up on the shame radiating off those of us for whom this is brand new.

In a recent class, Melissa told us to get out of our heads, and just go for it. Dancers call this going “full out,” and the secret is, even if you don’t know all the moves, the only way to not look like an idiot when you’re dancing is to just go for it. The more into it you are, the more you look like a performer interpreting a piece of music, and the less you look like an almost forty-year-old mother of two with plantar fasciitis.

Going full out is the energy of The Chariot. Sometimes that means faking it until you make it. Other times it means getting your brain out of the way of your body, and realizing you’re more prepared than you thought. There are dance moves that feel really complicated when they are slowed down but suddenly make sense at speed. I feel an indescribable euphoria when I find my body anticipating the next move of a dance, when I’m no longer in my head but in my body. It doesn’t always happen, because a lot of the time, the dance is hard enough that I’ve got to think my way through the whole thing. But every once in awhile, I let myself go full out. Those are the times when I leave dance class glistening with sweat, endorphins and pride surging through my veins for the rest of the day.

Melissa dances with emotion, pathos, and joy. Sometimes her choreography feels like an exorcism. There’s somatic magic in the moves she pairs with the music she picks. And every single time I show up, I get a little bit braver. So much of the past couple of years of my life has been about getting the fuck over myself. I’m realizing how much of my young life revolved around avoiding shame or embarrassment. Maybe some of that is just being young. Aging is a sloughing off of fucks given. Each birthday, I shed a new layer of fucks, until eventually, I’ll care only about joy, pleasure, and freedom. Maybe by eighty, I’ll finally take dancing pro.

Dancing is the closest I get to the release that came with drinking, but it's a deeper, more joyful release, full of catharsis instead of denial. An offering to my body instead of a flogging.

The Chariot doesn’t promise that the road will be easy, but it indicates that we’re on the right path, and encourages us to keep going. When I pull The Chariot, I imagine the joy and adrenaline I feel in the middle of a crowd of dancers, some of whom have decades of experience, and others who have only just begun. I close my eyes, the music starts, and I just go for it, full out.

Recommendations!

The Chariot is all about action. To harness the power of this card, try something new and really go for it. Dance, karate, pottery, mountaineering, candle-making! There are so many activities available to you. I don't know what you're into! And maybe you don't know either! The only way to find out is to throw a bunch of shit at the wall, and figure it out.

If you live in Los Angeles, you should absolutely try Melissa's Sunday dance class.

Nurture Shock: New Thinking About Children by Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman. This is a book about how to foster resilience in your children. I found it really interesting, and strangely at odds with my instincts, which is kind of a fun and weird reading experience.

What songs would you add to this playlist? When do you feel most in touch with the energy of The Chariot? Let me know in the comments!