Six of Swords

We can't go over it. We can't go under it. We've got to go through it.

My children have discovered Hamilton and they are singing songs from it all the time at full volume (if you’re a longtime reader, you know that my children sing from the moment they wake up until the moment they fall asleep — on the toilet, in the bath, eating dinner, walking through a room when I’m on the phone — sometimes I’ll ask my daughter to go get her sneakers and I’ll have to say something like, “No singing, just sneakers,” because otherwise she’ll go upstairs and twenty minutes later I’m still waiting at the door as she does Mariah Carey runs in her full-length mirror). Like most basic bitches, I love Hamilton, and I’m unashamed to admit that when the soundtrack first came out, I listened to it and sobbed. What were the tears about? They were about genius, friends, about the fact that a human man wrote that show and it took years and years and eventually it was done and it was on Broadway and it was pretty fucking special.

With my kids watching the Disney recording of the musical multiple times a week, and asking to listen to the soundtrack every time we’re in the car, I have been struck again by what is just, honestly, a profoundly beautiful collection of music. Sorry, Dolls, you can try to hate me for being a Hamilton lover, but I am embracing my earnestness as I near forty and I suggest you do as well.

At the moment of Hamilton’s death, as the bullet from Burr’s gun whizzes toward him in slow motion, Hamilton sings about his life and his legacy, he sings about the “great unfinished symphony” of America, and he sings this line that I think about a lot: “What is a legacy? It’s planting seeds in a garden you’ll never get to see.” Oof. My goodness. That’s a line right there, and it’s a line I think about whenever I pull the Six of Swords.

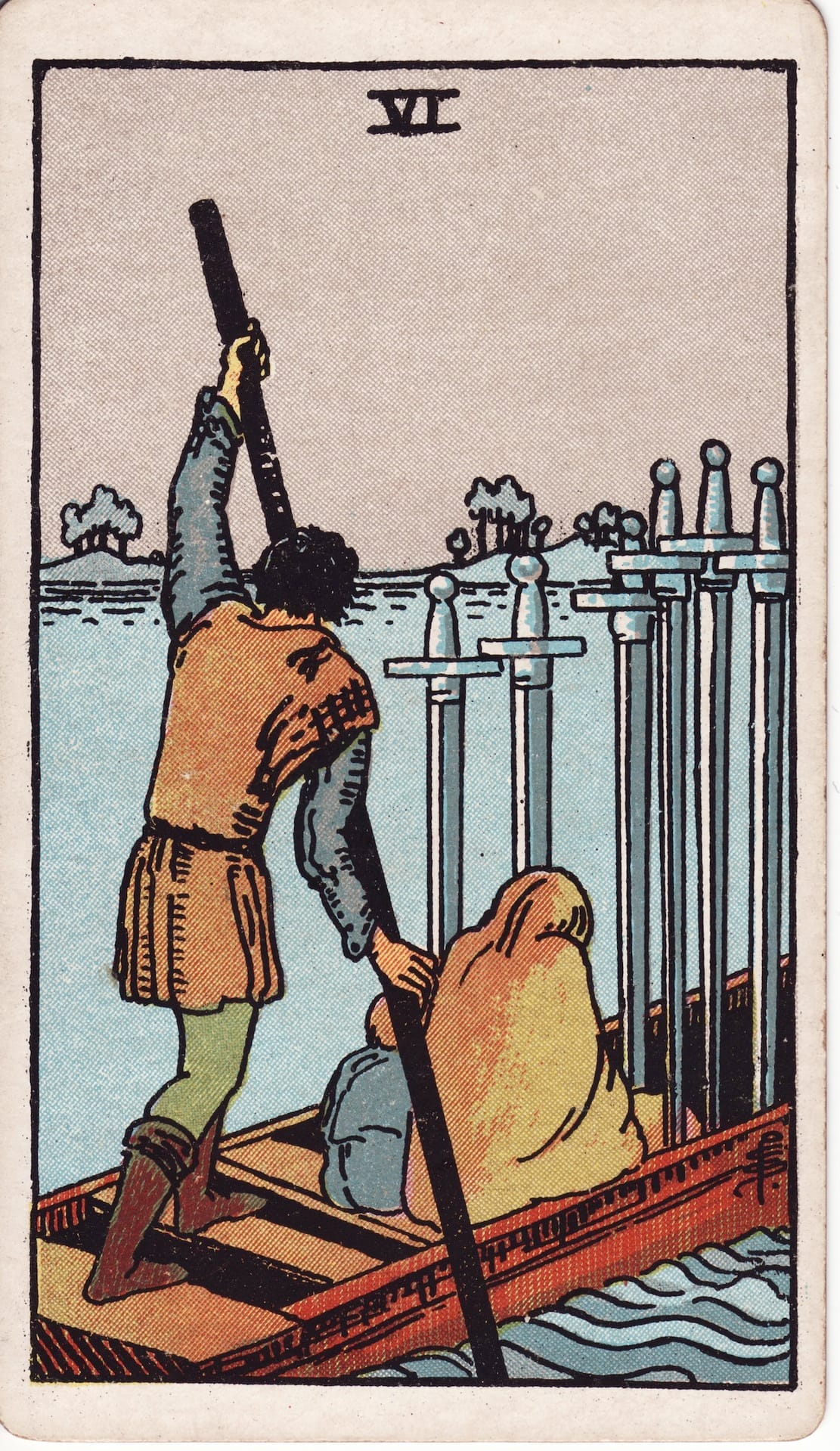

In the Rider Waite Colman Smith deck, the Six of Swords depicts a journey. A figure (who I read as a woman) shrouded under a blanket sits huddled beside a child, as another standing figure navigates a boat through unknown waters. The journey is a long and arduous one, away from conflict and tumult, toward uncertain shores. Peace is not promised, but the figures on the boat are hopeful, because there’s nothing left for them in the place they are fleeing.

The six of swords evokes an immigrant journey, a forced evacuation from the known world in pursuit of an undetermined future. The journey takes courage, and an ability to tolerate uncertainty, as you traverse rough waters in pursuit of transformation. That Hamilton line resonates in many immigrant stories — the struggle, sacrifice, and pain of one generation leads to the prosperity of the next. Even if that first generation never gets to experience the bounty, joy, or opportunity they left their homeland in search of, the future prosperity and freedom of their children and their children’s children is enough to make the journey worth it.

Maybe this is why the six of swords has been a sticking point for me, why it’s been hard to write about and why I’ve written and deleted like seven different versions of this essay before just forcing myself to publish something — it is hard not to see the strange combination of horror, suffering, and hope of the six of swords and contend with the cruelty of America’s new isolationist vision of the world. Don’t come here, our president tells the rest of the world, as students are snatched up in the streets and disappeared, as fathers are ripped from their families and illegally sent to hellish El Salvadorian prisons, as children stay home from school because they’re afraid if they leave their parents’ side, they may never see them again.

“You won’t have a country anymore,” Trump warned throughout the election (unless I’m elected, unless we build the wall, unless we deport anyone who doesn’t “belong” here). We’ve long been a country of contradictions and cruelty, built both on the concept of inalienable freedom and enslaved labor. The dream of America — a place of opportunity, ingenuity, and freedom of expression — has never been fully realized, but it remains a worthy dream. I don’t need to belabor the hellish new reality we’re living in — we’re all watching it happen — but I can’t help but think of all of the immigrant families who saw America as a beacon of hope, a promise of safety, a shining city on a hill, and how quickly Trump has destroyed whatever kernel of truth was left in that flawed but worthy dream.

But this is a newsletter about magic and feelings (NOT POLITICS), and I need magic now more than ever (I could definitely stand to have fewer feelings though). The Six of Swords is a card about journeying and reflection. Sometimes the only way to understand how we’re really feeling is to walk away for a little, to get a fresh perspective, to break the pattern and routine that isn’t serving us.

The Six of Swords comes after the tumult, conflict, hurt feelings, and chaos of the Five of Swords (because that’s how numbers work). The six of swords is a retreat from the five’s conflict, an optimistic step toward a new future – hope without guarantees. There will be obstacles, pain, suffering, and hardship on this journey, but the only way out is through.

Sometimes I imagine that all three figures in the boat are parts of the same self. The child self is afraid and vulnerable, unable to protect themself, at the mercy of the journey. The huddled woman is protective, harboring her own doubts and fears but staying strong and focused for the child. She’s also riding in a boat stabbed through with swords, wounds inflicted by whatever conflict she’s fleeing. She’s not sure she’ll make it to her destination before the boat sinks, but she has no other choice but to take the risk. Both these figures are emotional, exhausted, and just trying to survive. This is why you need the boat man.

The boat man is your highest self, the self perched above at a higher vantage point where he can see a lot more of the river. The boat man’s concern is ferrying his passengers to safety, and he knows that there is nowhere to go but forward. Yes, there may be alligators (or hippos!), but standing in the middle of a war zone worrying about hippos won’t get you any closer to freedom and peace. So you navigate the river because you have no other choice, you patch the leaks you can patch, and you put one foot in front of the other. There is no way of knowing what awaits you at the end of this journey, but there is nothing left for you on the shore.

The only way out is through.

Which reminds me of this story that I always used to read to my children when they were little:

We’re going through it right now, guys. The world is scarier than it has ever been (in my lifetime at least), and I am filled with dread all the time. Sometimes I feel hopeless, like any optimism I can muster is merely a defense mechanism, the mind lying to itself. But on other days, the California poppy bulbs I planted are beginning to sprout, and my 18-month-old nephew is covered in mud and riding his bicycle naked except for a helmet in the yard. There are many dark days ahead of us, to be sure, but we don’t get to choose when we are born. For that matter, we don’t get to choose our parents (or their tax bracket), our country of citizenship, our ethnicity, race, gender, ability, or sexuality — and yet, so many of us are being punished for these immutable traits every day. The best we can do is hang on to one another, to pilot our boats through these rough and tumble waters toward a shore we can only imagine. We do what we can to fight back and protect one another, planting seeds in a garden we may never get to see.