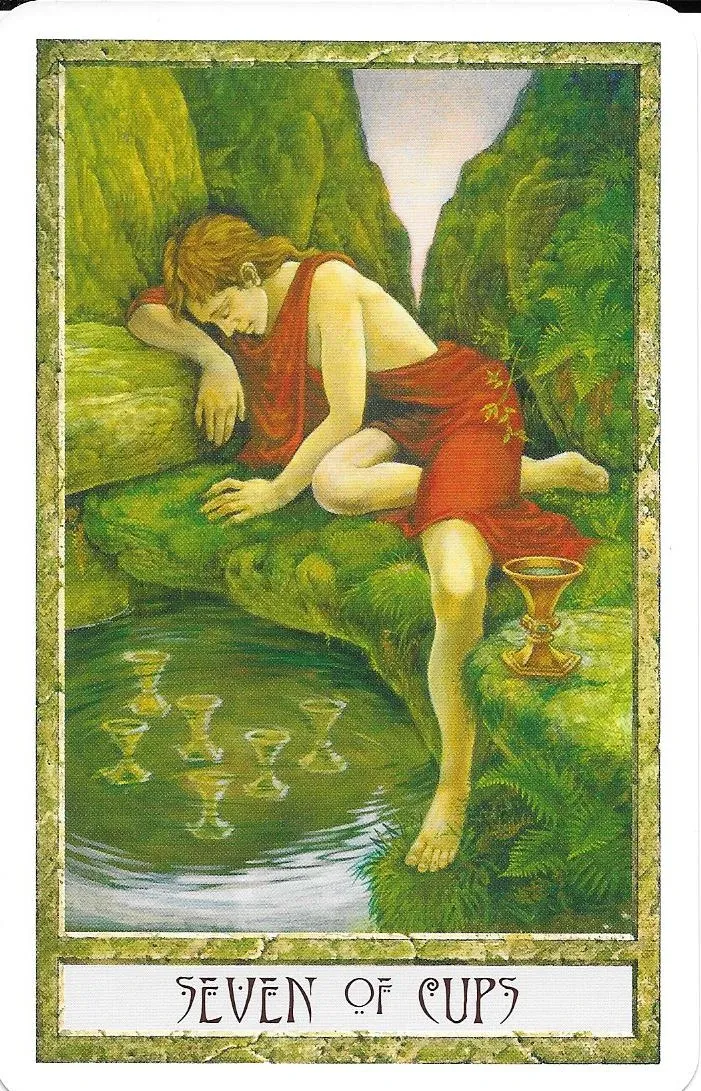

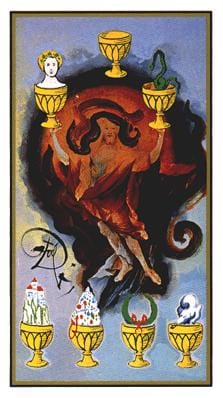

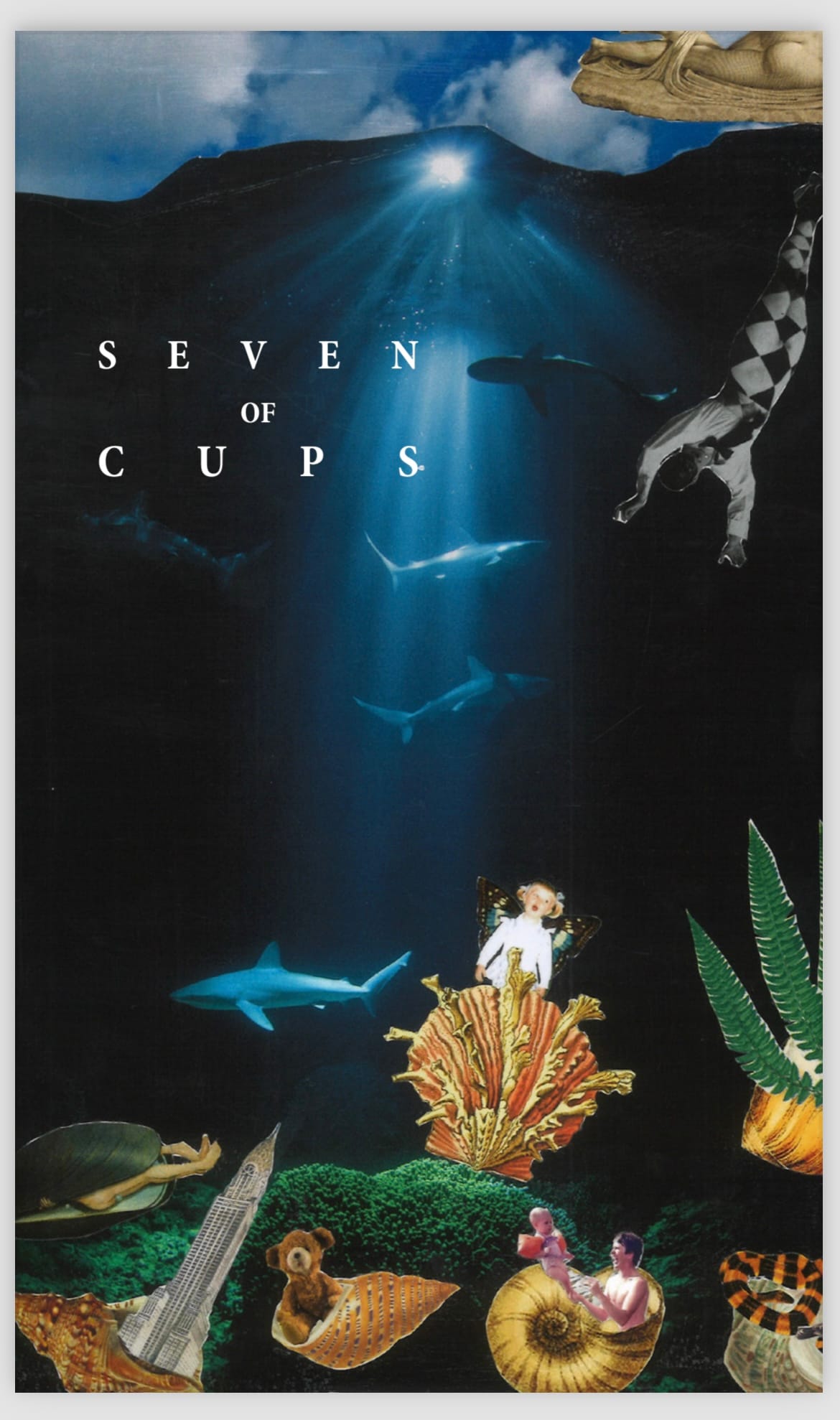

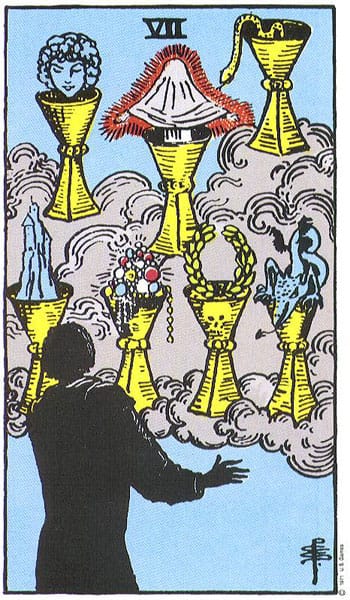

Seven of Cups

I was three years old when I sat on Bill Cosby’s lap and ate Jell-O gelatin.

Seven of Cups Playlist

I was a kid for a living. I was a charmer, a liar, a con artist, who would write letters to myself from God for other people to find. There are many different ways to be a child, but the only way I knew was to pretend.

I was six years old when the director pulled my mother aside to ask her to speak to me about professionalism. I’d been asking for hugs in rehearsal, and it was getting in the way of the work. I recall the follow-up conversation with her in pieces. Her own girl traumas roiling beneath her skin as she tried to explain that it was inappropriate for a grown man to hug a little girl. Inappropriate how, I wondered. I didn’t know a hug could be dangerous.

My mother has stories she has never shared with me, maybe some she’s never told a single soul. She was the youngest of five and her parents couldn’t control her and she was wild and beautiful and sometimes scary things happen to beautiful girls (though she’s always vague about the details). She wanted to protect me, wanted me to know that I could tell her anything, that even if someone told me that they’d hurt her or me or everyone I've ever loved if I told her something bad, I should still tell her and she’d always believe me. What kind of secret would that be, I wondered.

My mother’s stories live in her bones somewhere so deep they are almost forgotten. Someone took a carving knife and etched them there. Sometimes I will get a whiff of a story, but it hangs in the air only for a moment, before it is gone, whisked back into the recesses of her body where she won’t let us see. Because she was so serious about protecting me, I knew that I would never keep anyone’s secrets, not even my own. I didn’t want stories carved into the white of my bones. My bones already had her stories, not carved with a knife but rubbed on like with a pencil on tracing paper.

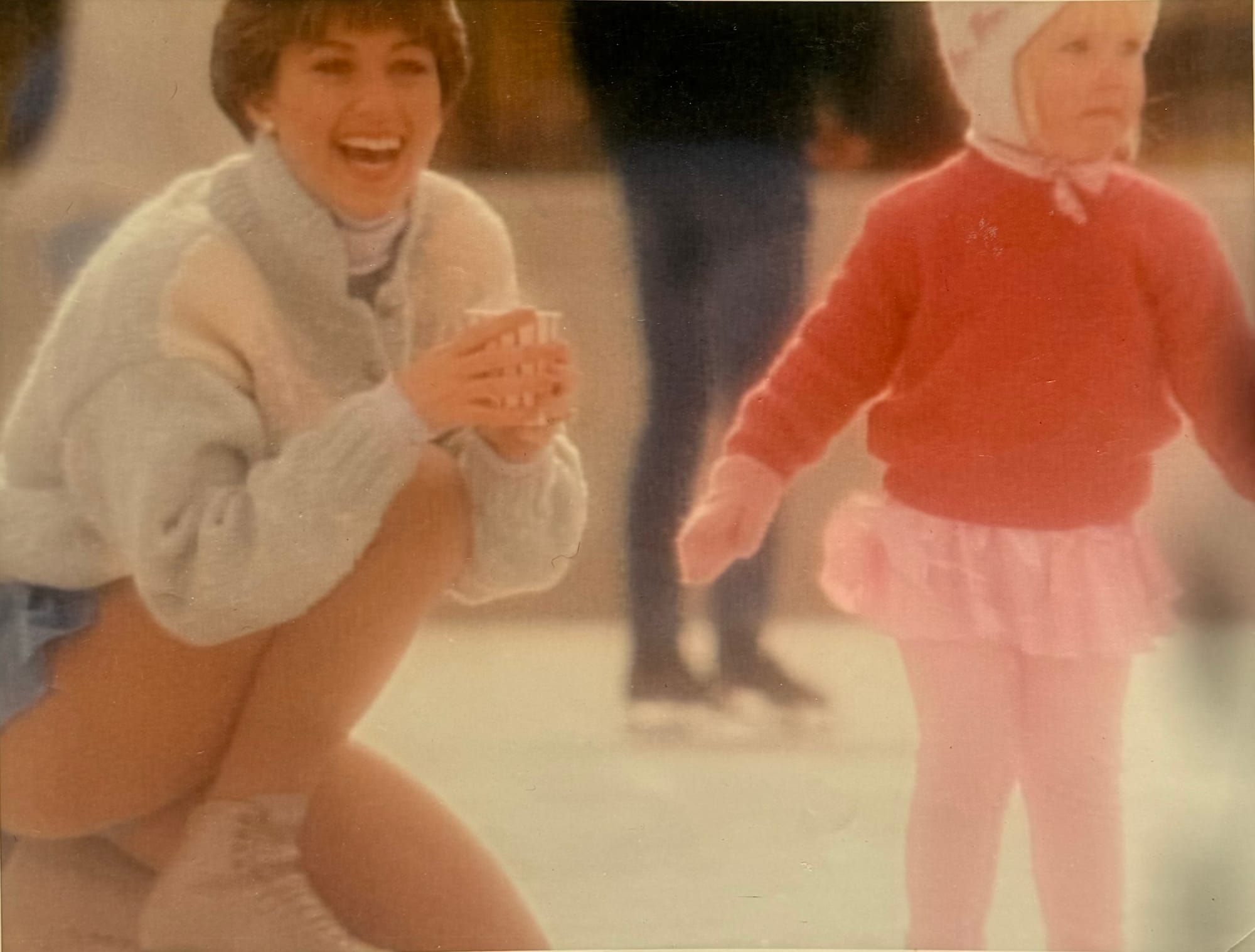

My mother wasn’t a stage mother. She was an athlete. She was twelve when she started figure skating, geriatric really, wouldn’t amount to anything at that ripe old age of twelve. Everyone told her she’d better give up, or think of it as a hobby, nothing more, because kids her age had been competing for almost a decade and she was very far behind. I’ll show them, she thought, and she did. She threw herself into it, punished her body until it conformed, skated the same edge, carving stories into the ice over and over again until she got it right. She had the best spread eagle for miles around. Her spins were legendary. Her parents didn’t know what to do with her, but she found a career when she was twelve and she clung onto it for dear life, and it saved her.

Unlike the dozens of blonde-haired blue-eyed girls I saw at every audition I ever went on, I wasn’t living out my mother’s dream. She wasn’t waiting in the wings, mouthing the words because she secretly hoped I’d break an ankle and they’d ask her to step in at the last minute. No, she had her own art form, her own sport, and she knew how hard it was to start when you’re twelve and past your prime. And because my father had been there, because they had met when they were twelve and started dating when they were fourteen, and he had lived through the body punishment and the hard work, he had made her promise that I wouldn’t be a figure skater.

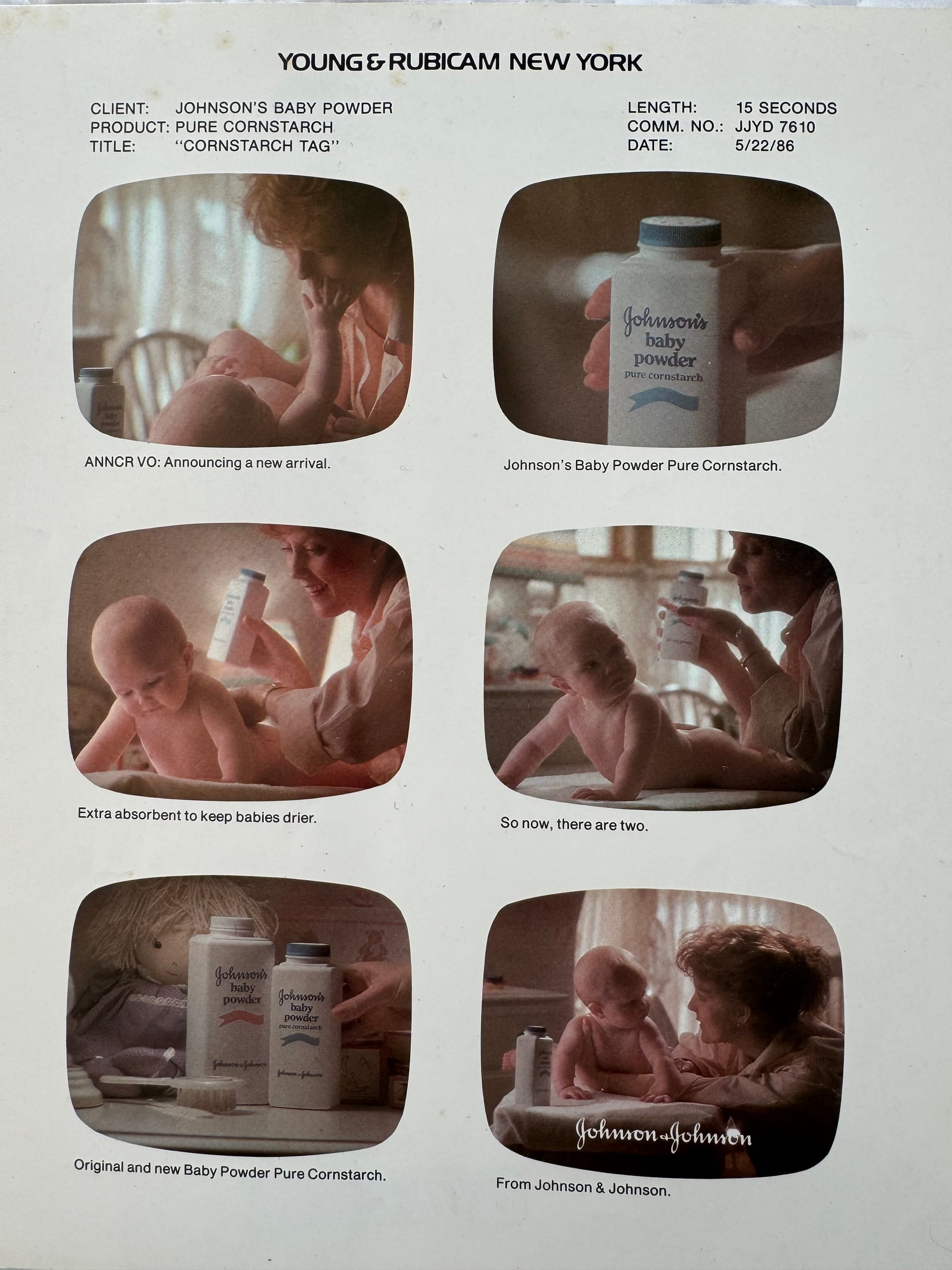

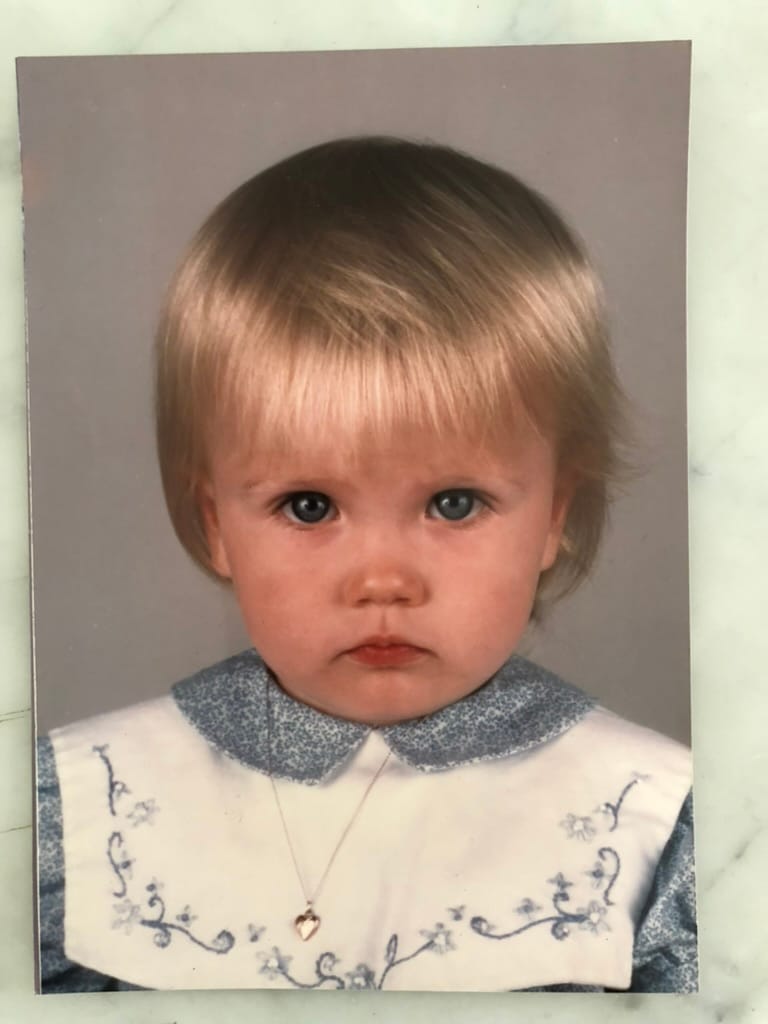

I was six months old when I landed my first starring role. Precocious. Ahead of the curve. Not some dried up, shriveled old twelve year old, but a talented, well-behaved pre-verbal baby who’s bare butt was so iconic it could sell Johnson’s and Johnson’s baby powder, before everyone knew it gave people ovarian cancer. (Not my butt, the powder, my butt CURES cancer).

I was three years old when I sat on Bill Cosby’s lap and ate Jell-O gelatin. I had a fever, goes the story. The other child, the child they’d hired to do the commercial (I was just a back-up, you see, the second choice), couldn’t concentrate, couldn’t remember the lines, didn’t have the charisma. My mom was about to leave and drive me to the doctor when the assistant director came in to call me up to the big show.

This was peak Cosby. Cosby long before the revelations. It’s a story that gets told round the Christmas trees and the campfires. The first of many stories about how compliant I could be, how professional, even at age three. Even then, when my body was burning up and my guts hurt and my nose was running, I could turn on the charm when I needed to. Other kids didn’t have the attention span, couldn’t hack it, spent their time picking their nose or couldn’t find their light or take direction, but me? I could sit there on Bill Cosby’s lap with a 102 degree fever and wrinkle my nose and say the lines I’d memorized and light up the damn screen.

My Jello commercial.

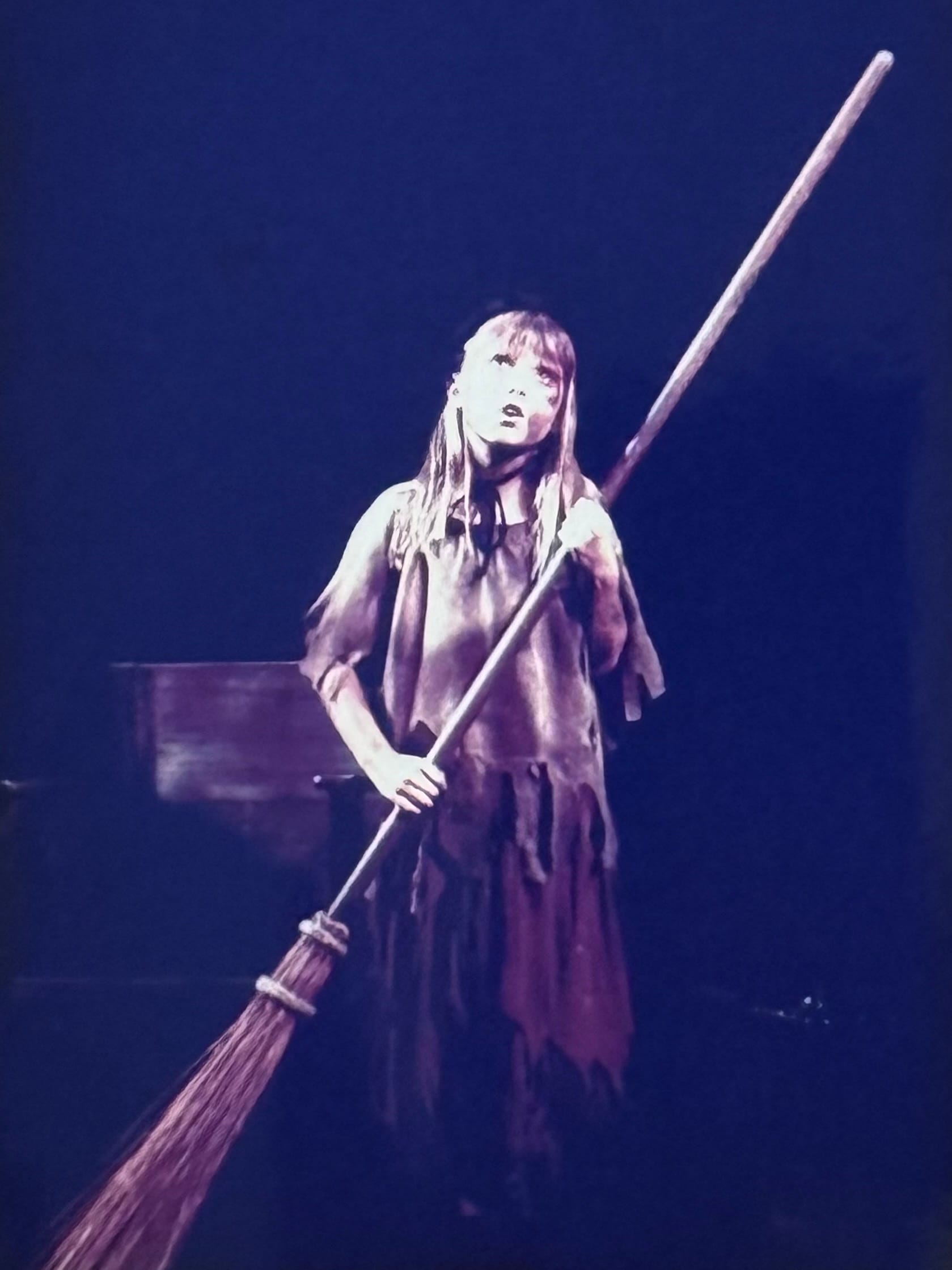

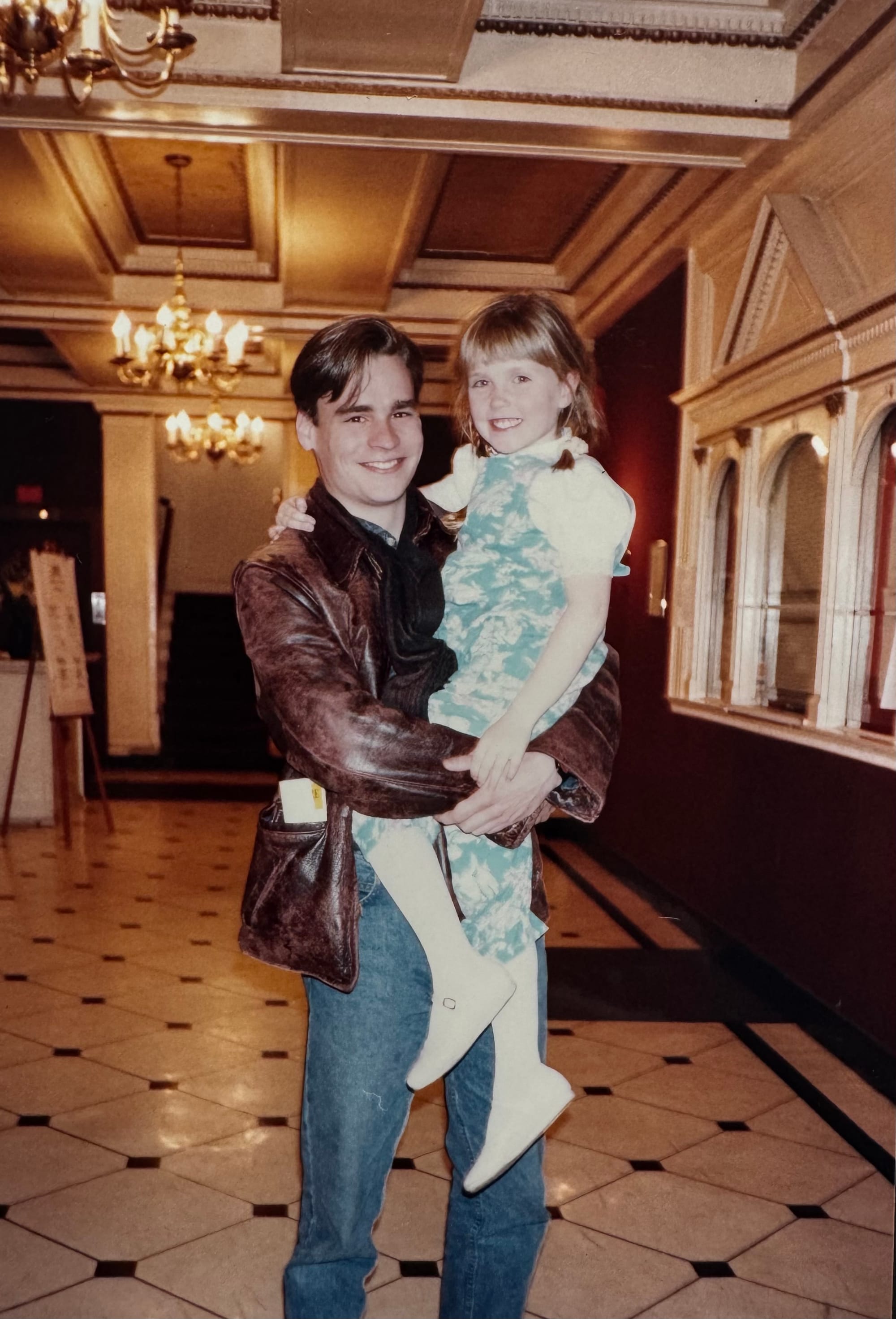

When I was six years old, my mother took me to an audition for an Off-Broadway musical called Opal. I had never sung before except in the car. I was six years old and all the other kids were nine and they’d played Annie or Nala or Cosette, they’d been hardened by the business and their parents were kooks. We were well adjusted and I was a six year old who knew how to behave like a grown-up. I was a goddamn professional. I got the part.

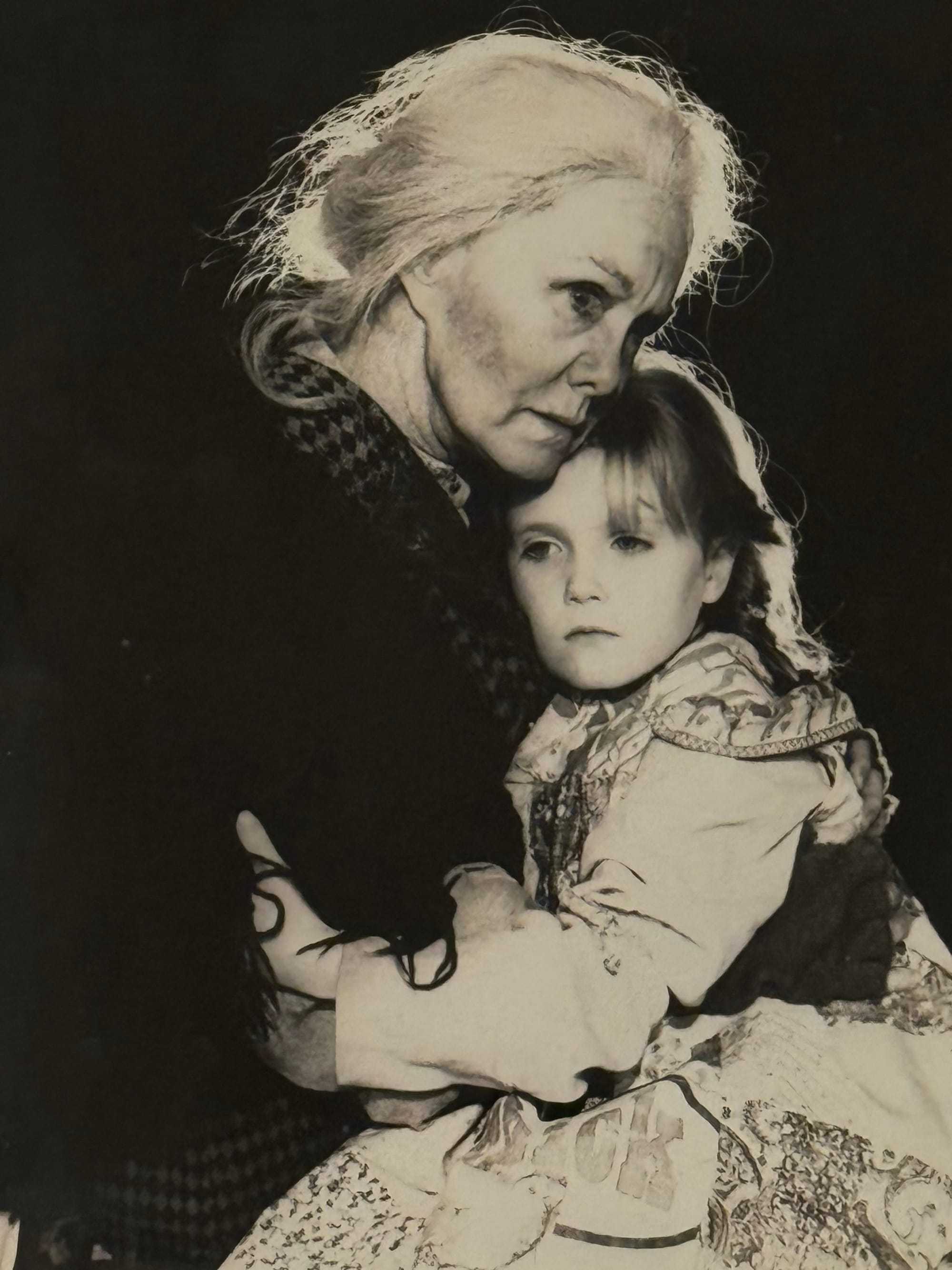

I was the only child in the show, and I was on stage for the entire two hour runtime. I sang two solos. I acted opposite adults, including Marni Nixon. Twice I peed my pants on stage, urine dripping down my tights, pooling at my feet. Luckily the stage had slats so the pee had somewhere to go. The story of peeing my pants (which mortified me, of course, and filled me with a kind of shame that was so electric it felt like it might kill me even years later) was told and retold as evidence of my professionalism. Even in the face of a full-to-bursting bladder, I didn’t flinch. I performed.

Me and Marni Nixon in Opal at the Lamb's Theatre Off-Broadway.

My professionalism translated into my school plays. While I was still performing in Opal, I got the lead role in the second grade production of Alice in Wonderland. The day of the performance, I had the stomach flu. I didn’t tell my parents I was sick because I didn’t want them to keep me home. I didn't have an understudy! This was elementary school! The show must go on!

Only once did I have to run backstage to vomit, but then I was right back out there, singing my solos in the cafeteria. Another story of my remarkable professionalism. A story of punishing my body for its human weaknesses, and pushing through misery to get the job done. Whatever it took.

At fourteen years old, I played an injured hockey player in an episode of NBC’s Third Watch. Though I thought this was my triumphant return to the spotlight after the horrors of puberty, this would be one of my last acting gigs. We shot the scene at an outdoor rink in Manhattan. It was the middle of January and it was raining. There was an inch of freezing water lying on top of the ice. I lay down in that frozen ice water for hours, trying not to shiver, emoting my face off, saying the lines. Between takes, a wardrobe person would point a hair dryer at me so I wouldn’t get frostbite. Everyone kept praising me for never complaining, telling me how I was a pleasure to work with, what a professional, how I’d have to come back and play another role, a bigger role next time. I was filled with a sense of accomplishment, even though I couldn’t really feel my feet.

Law and Order. I was the killer.

Child acting isn’t acting. It’s something else. Something sneakier and when it’s done well, its own kind of craft. It feels like getting away with something. Here’s what it takes to be a solid child actor:

You must be able to memorize lines. And to get the job, you must memorize your lines for the audition so they know you can do it. In my heyday, I’d go on multiple auditions in a day, at least a handful every week. And memorizing took time and effort and work. You must be willing to sacrifice — play dates and sleepovers and bike riding with the neighbors. How badly do you want it? (what is “it,” you ask? It’s hard to say, but it’s important that you want it).

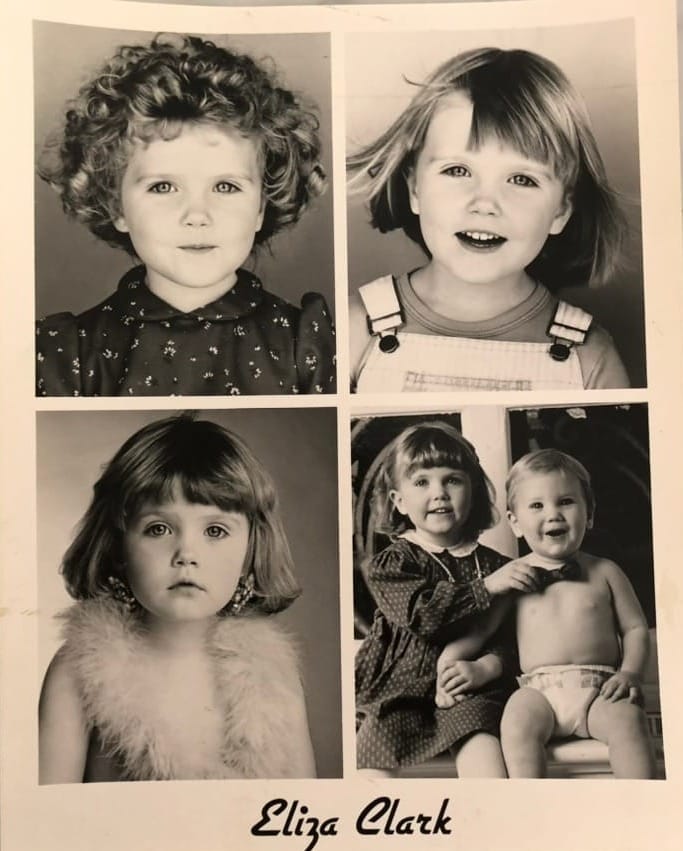

You must be small and precocious, smart and professional. Small is hard unless you’re blessed with a genetic disorder or you won’t even get a whiff of puberty until your late teens. I always felt too big and too tall, though I was solidly in the middle of the normal percentile for my age group. But no child actor is in the normal percentile for their age group. I was constantly auditioning against kids who were four or five years older than me and three inches smaller. I felt like a freak. But there wasn’t much to be done about my bones and their incessant growing. We hollowed out my shoes to make me smaller. I bent my knees imperceptibly but effectively when the casting directors took out the measuring tape (and they always did). The size of me was important to adults. That was something I knew. Because the smaller you were, the easier it was to fool everyone into believing you were a child.

The other part came naturally. Precocious, smart, and professional. I would read novels while I was in the waiting room. Novels for kids much older than I was, sometimes even novels for grown-ups. I would never fidget or whine. If my brother accompanied us, I’d make a grand show of kindness toward him, illustrating both my magnanimous qualities and my ability to collaborate with anyone, even a boy. He was in on the con. We’d be bickering in the car, poking each other and squabbling like siblings do, but the minute we got into the casting office, we’d turn on the charm. We knew that many jobs were won and lost in the waiting room.

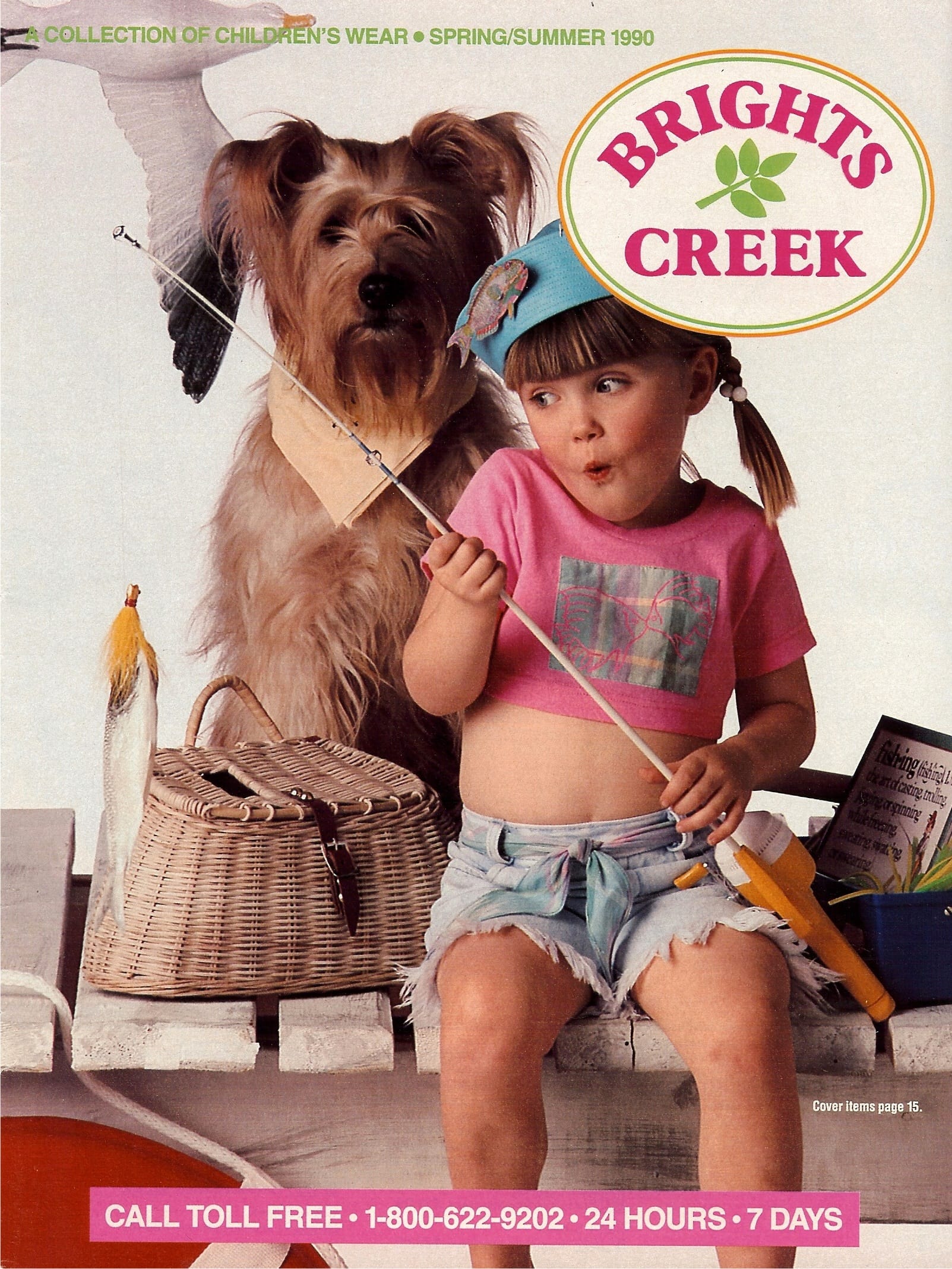

To be a child actor, you must be a perfect facsimile of a child, but without all the annoying unwanted attributes people think of when they picture “child.” Regular children are whiny and selfish, they’re insane when they’re hungry, they can’t control their impulses, they fidget and cannot concentrate, like goldfish. Professional children look like kids, with their hair braided and their overalls and they say the darnedest things. But professional children are surgeons in an operating room or astronauts on a lunar mission, performing delicate and complicated maneuvers after years of hard work and practice.

When you are asked questions by the adults in the room about your personal life, they want to be made to feel that they are in the presence of a real life human child. “What do you for fun?” they might say. They do not want to hear that you haven’t had a play date in weeks because you keep having to be picked up from school early for auditions, or that you don’t like playing piano because it feels like work, but you have to do it so you can learn to sight read music (a very valuable skill). They want to hear that you like “reading and writing stories and playing soccer with your friends.” That’s something a real child might say, and you are an actress, so you know how to embody a character.

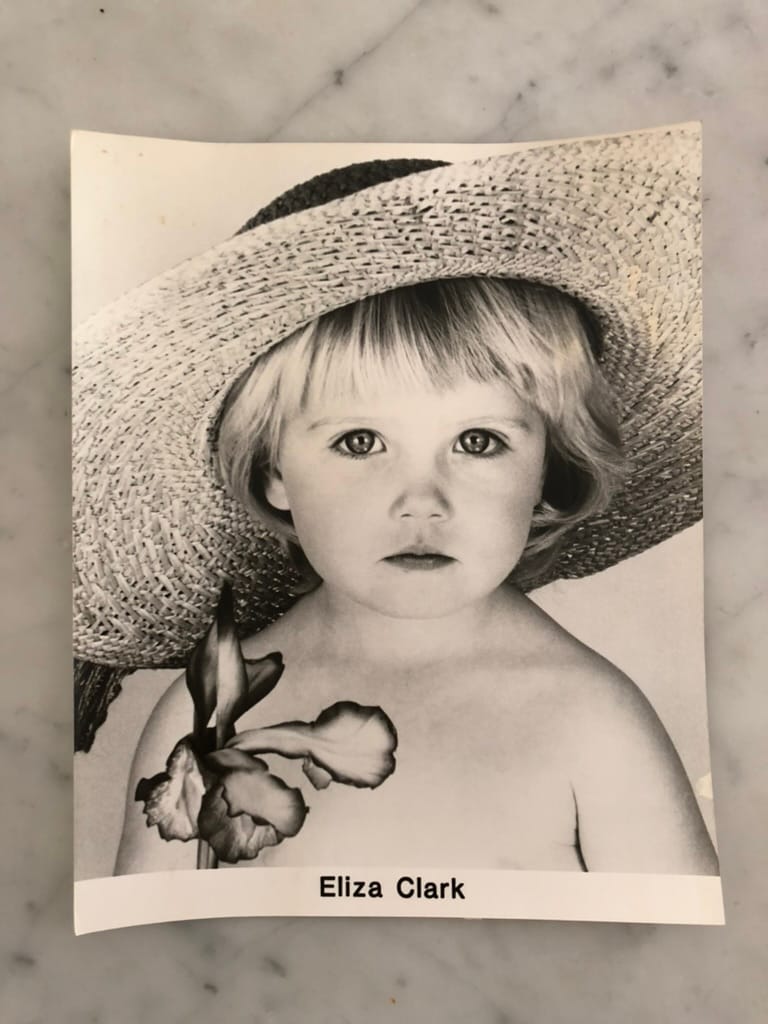

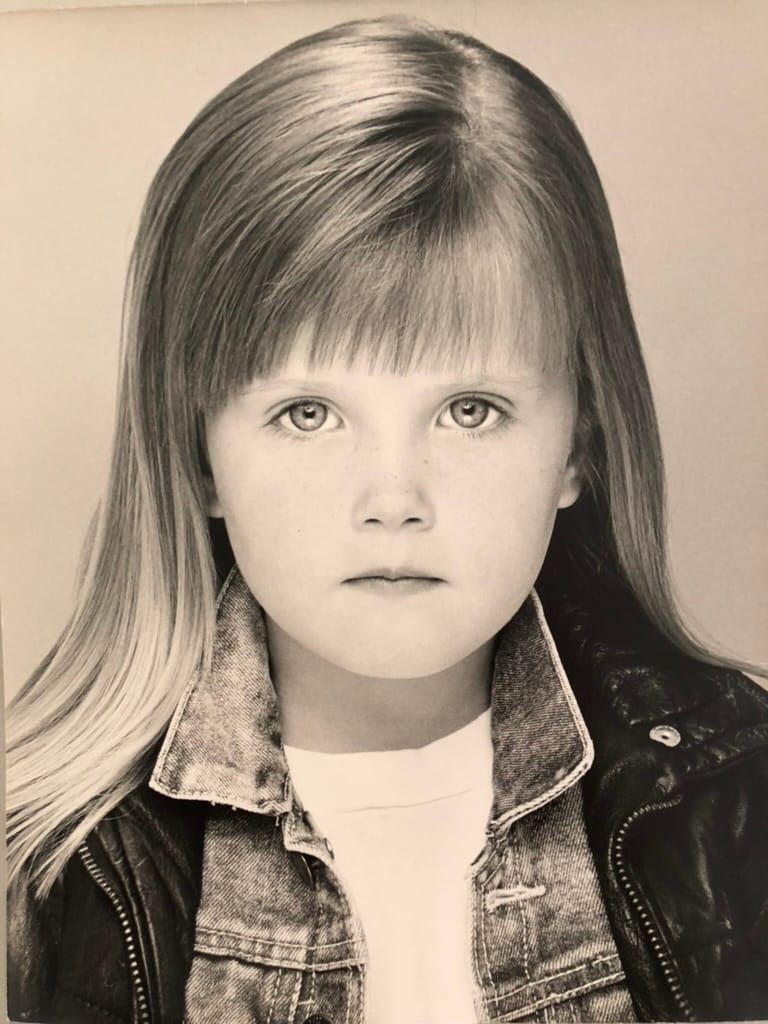

Of course, you do love reading and writing stories and playing soccer. And there are plenty of days where you get to play with your friends in the woods near your house, and you’re on the soccer team and you make it to a lot of the practices when you aren’t working. But you’ve told the story of your life so many times in casting offices that it’s hard to remember which things you actually like, and which things are just part of the character of “Eliza Clark, child” that you play in the presence of adults.

Over the years, my brother and I met so many psychotic parents who were not our own. You could see it in the waiting rooms, the moms (it was mostly moms) who were dieting with their eight-year-olds, who had wanted to be actresses a million years ago, who were living in a one bedroom with eight kids because they’d left Dad in Florida and were hoping to strike gold.

My parents were NOT THAT. For one thing, my mother had no interest in stepping in front of a camera, and my father was baffled by the whole thing. But my mother had also gotten lost in her family, the youngest of so many kids. My mother was the kid with undiagnosed ADHD in the super conservative Catholic military family who cart-wheeled down the aisle at the Vatican, the kid who shot out of bed at 4:30 in the morning, who would jump from the balcony into a briar bush if her brother dared her to. My mother was a wild child who only figured out how to contain her manic energetic fire when she was doing repetitive, competitive, athletic feats.

The money I made was used to pay for our lessons, our sports, our schools, and there was plenty left over for me when I got to high school. When I told my parents I hated posing for pictures, we stopped modeling cold turkey.

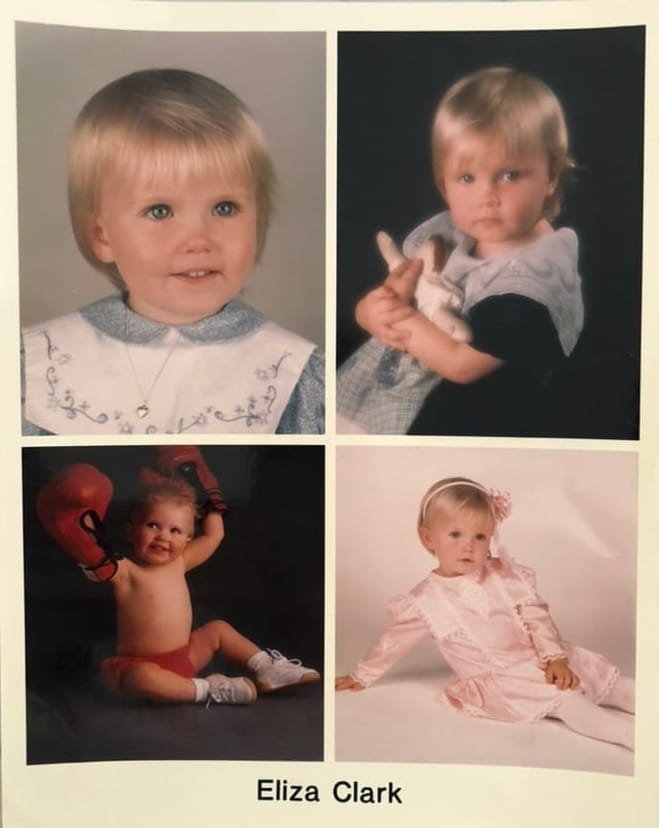

My modeling was iconic while it lasted.

My mother sacrificed her time, her life, her career, her sport, her body, everything, every single day for us. And though I think that probably no child should ever be a professional, I wouldn’t take it back. It’s important to say: it was really fucking fun. I loved being on stage. In spite of all of the many things I am ashamed of (my body, my teeth, my personality, my too-muchness, my inability to be mysterious at all), I have never for a moment doubted that I am capable of great things, that I can accomplish anything I put my mind to. That’s my mother. She made me believe in myself.

The seven of cups is about self-delusion, addiction, the insatiable desire for something to fill a spiritual hole. The seven of cups offers seven cups, each with a promise of an entirely new life, but the lesson is that none of the cups will actually give you what you need. That has to come from within. The seven of cups makes me think of that three year old with a fever on Bill Cosby’s lap, or that second grader puking in the bathroom between scenes of the school play, the six year old who peed on stage and kept on singing.

I have spent much of my life in pursuit of an answer to the need inside of me. Most of the time it comes back to that little girl in the audition room hoping to be chosen. I learned very early to put my body aside — you have to pee? Hold it. You’re hungry? Well, you can’t eat in your wardrobe. You’re tired? Push through it. You want to cut your hair? Your employers like it long. Once, I was reprimanded by a stage manager for getting too much sun — “Cosette is never allowed outside” they said.

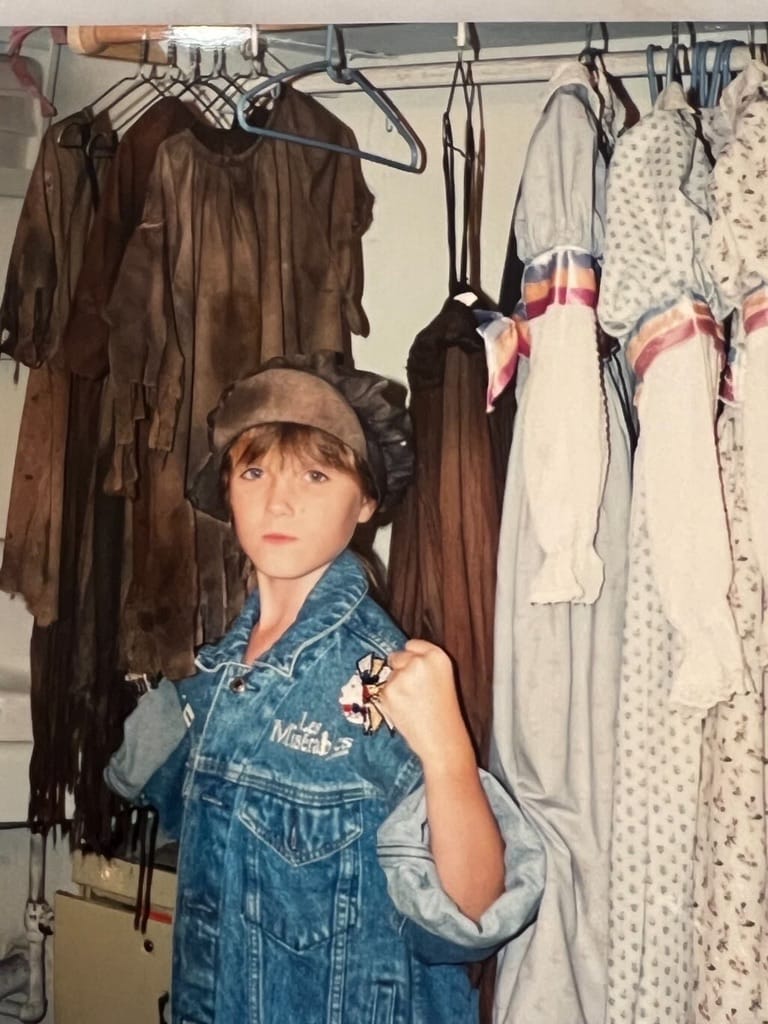

Backstage at Les Miserables.

My feelings are complicated, because I wouldn’t take it back. I traveled to places I never would have traveled, I knew I could make a career as an artist. But my love/hate relationship to my body, to food, to alcohol… it all began when I was way too young to understand that my worth was inherent, not conditional, that I was lovable regardless of my resume.

I got to meet interesting people and do interesting things. Top Row: Me with Brooke Shields and Louise Fletcher at a benefit for Deafness Research (middle picture is me performing at the benefit), Second Row: Dorothy Hammill and me in a commercial for NutraSweet, Robert Sean Leonard (super sweetie) came to see me in Opal after I said approximately three lines in Swing Kids, a movie he starred in.

Now I am thirty-eight years old, and I feel my best when I am producing. The harder I work, the happier I am. I’ve quit drinking, which only takes one of the seven cups off the board. I frequently find myself fantasizing about waking up impossibly thin. But because I’m unwilling to put my pancreas through unnecessary and untested stress, it’s unlikely to happen no matter how hard I run up a mountain in one hundred degree weather. In the absence of the perfect body, I throw myself into work in search of happiness.

The seven of cups reminds us: our value cannot be found out there, it has to come from within. I’m lucky I have a job that I love, one that makes me feel good about myself. But I don’t want my value to come only from what I can produce. I’m trying my best to come back into my body, to see the inherent value of just waking up in the morning alive. I have not mastered this. I may never master it. But I’m trying.

Thank God I’m no longer an actress.