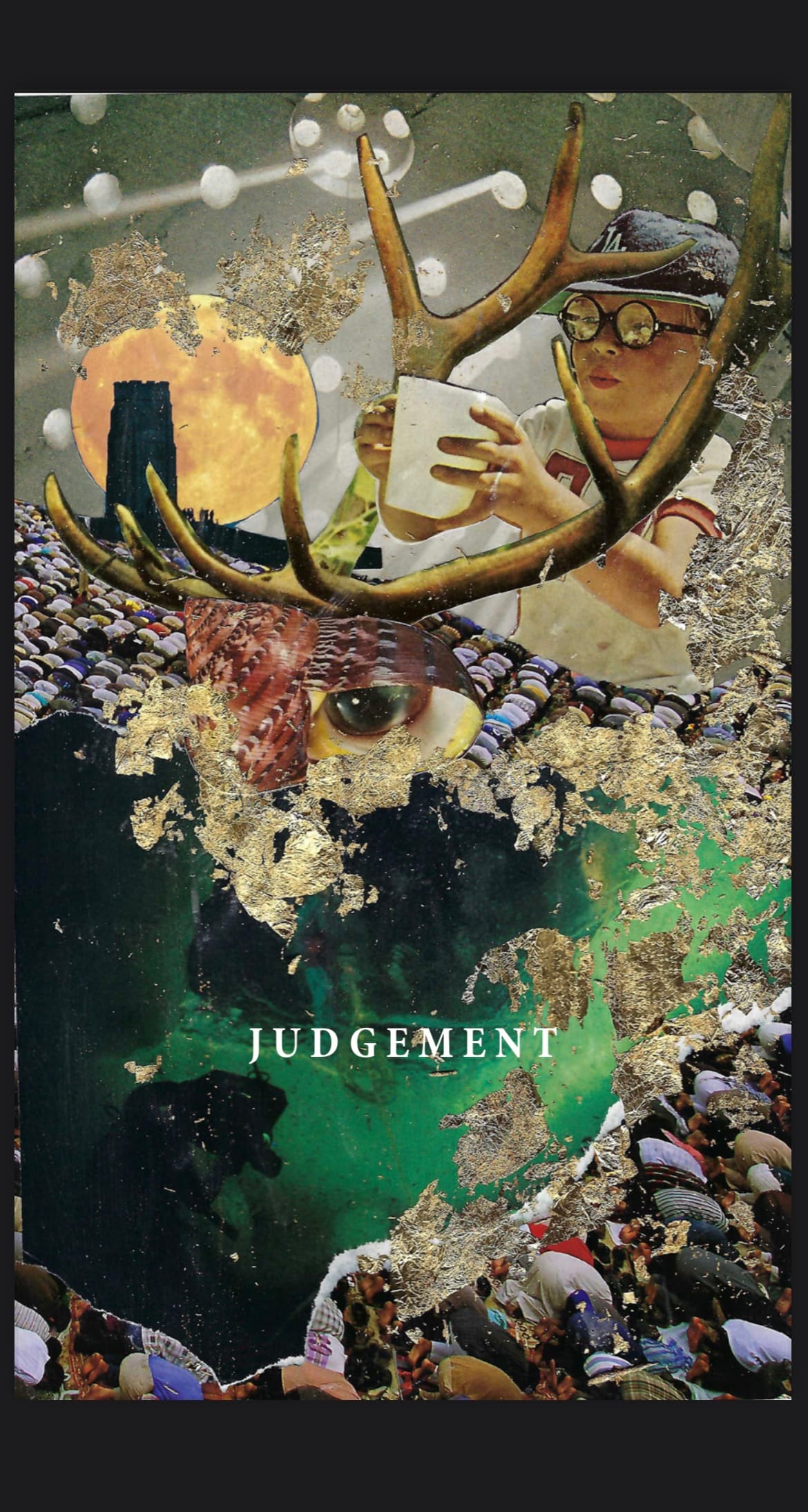

Judgement

A wide-ranging conversation with writer/director Liz Garcia about writing, motherhood, filmmaking, expectations, patriarchy, the creative process, grief, and more.

Playlist

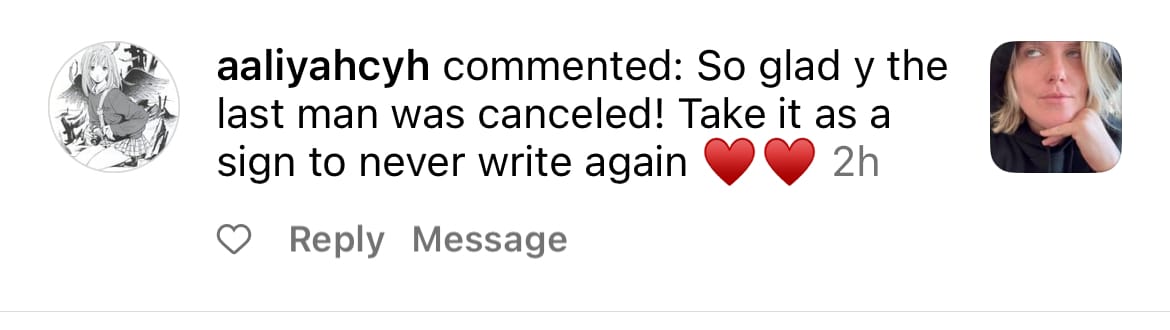

Before I dove into writing this morning, I opened my instagram mentions to a comment left on one of my most recent posts: “So glad y the last man was canceled. Take it as a sign to never write again.” This was followed by two heart emojis. A DM from the same random person read “Never write again, heart emoji.”

Wow, I thought. Wow. I’ve been caught.

What could have possibly possessed this person, almost a full year after my show was REMOVED FROM THE PLATFORM, to reach out with this helpful unsolicited feedback? We never know where our teachers or our lessons are going to come from… but also, the timing is serendipitous! Today, I’m writing about Judgement.

I’m no stranger to criticism. It comes with the territory of being a writer, but man oh man is it hard to keep yourself from combing through the muck to find confirmation of your worst fears. Aaliyah from Southern Methodist University thinks I should NEVER WRITE AGAIN!!!! SHE IS ABSOLUTELY RIGHT!

If you’re a troll on the internet and you think you can hurt me, think again. I’m a mother. Unsolicited feedback is the air I breath, Buddy. My butt is too big! My boobs are floppy! I’m the worst mother in the world! This is the worst day of their lives and it’s ALL BECAUSE OF ME! You want to externalize your own anxieties, fears, and insecurities? Have a kid.

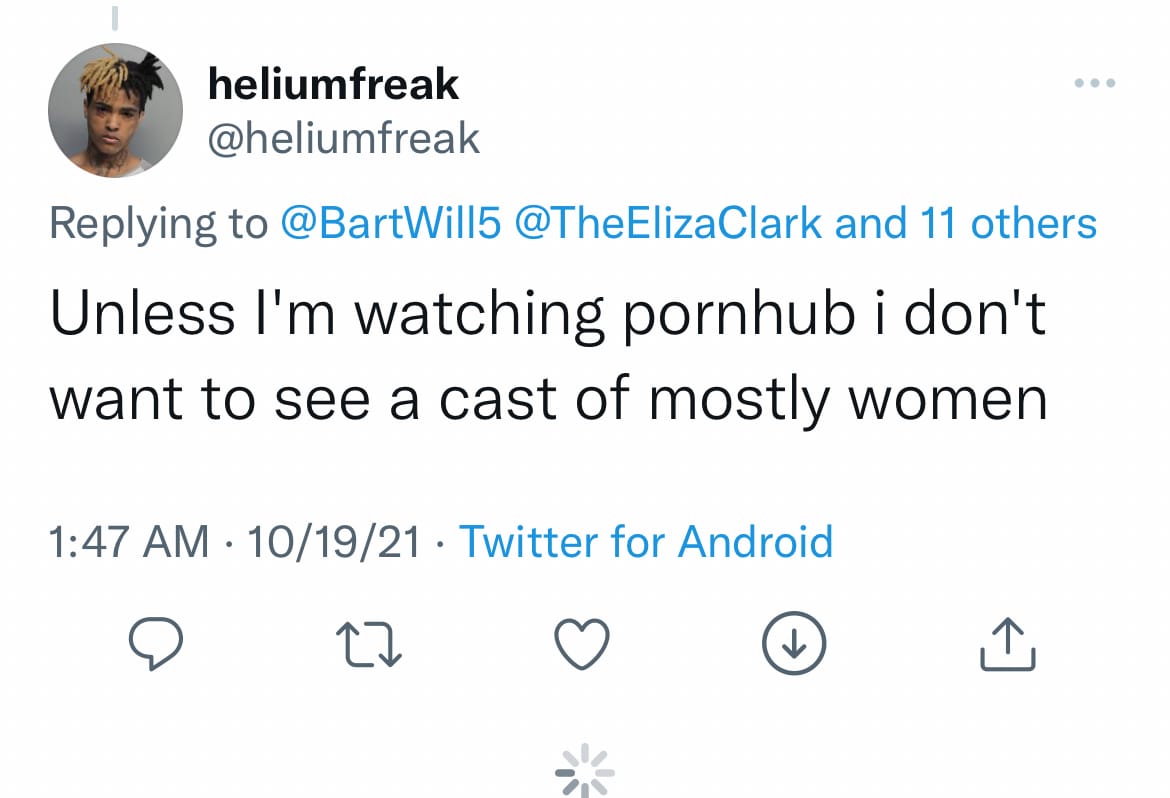

It’s because of my children that I can laugh at the guy who tweeted about my show, “Unless I’m watching pornhub, I don’t want to see a cast of mostly women.”

Internet strangers are pure id, lying in wait for the perfect moment to strike. I like to imagine that Aaliyah from Southern Methodist University woke up this morning in a cold sweat — today’s the day, she thought, I need to tell this fucking woman to stop writing. Aaliyah, truly and from the bottom of my heart, if I could stop, I would.

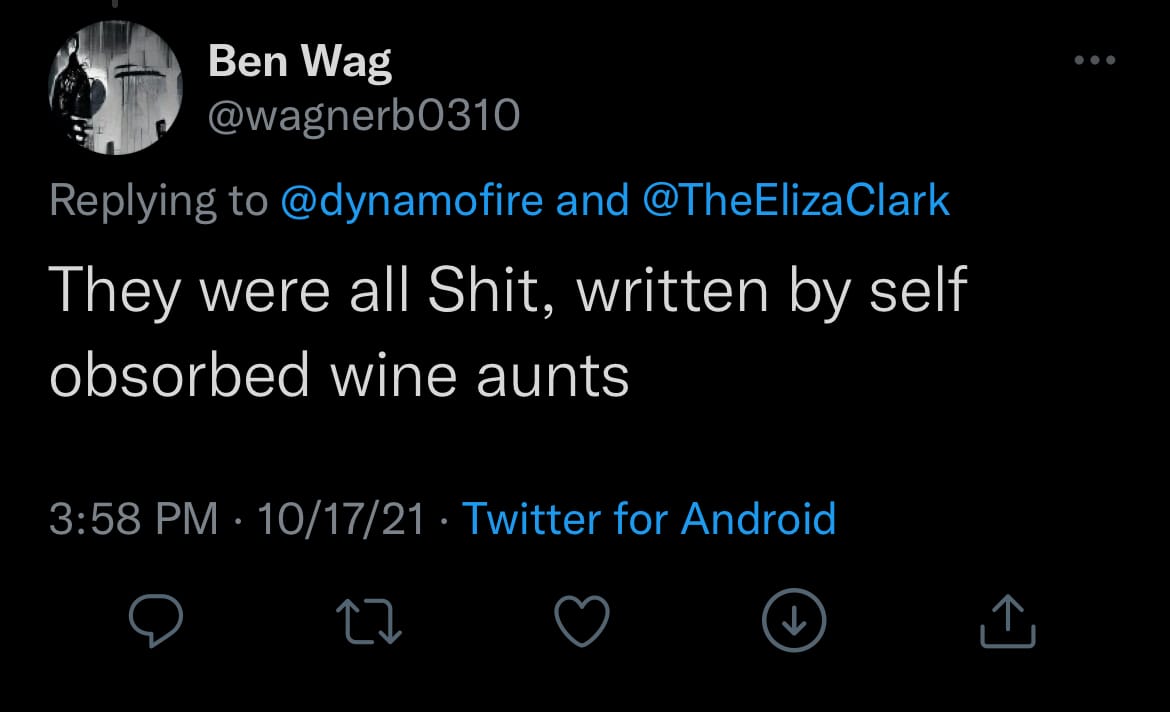

I keep some of the worst things people have said about me online screenshotted on my phone. That way, if I need to doom scroll, but I’m also feeling narcissistic, I can make the existential crisis about me instead of the state of the world. A walk down memory lane through the tweet that accused me and my writers of being “self-absorbed aunts,” or the many mouth breathers who screeched “GO WOKE, GO BROKE” into the cavernous abyss of the internet.

Judgement is the penultimate card in the Major Arcana, and in spite of what you've read so far, it’s positive. Judgement is about the many good decisions that lead to present victories. It’s about exercising your own good judgement, staying in line with your purpose and achieving your objectives. But it can also be about external validation and accolades, and I'm here to tell you that shit is a trap.

Recently, I spoke with writer/director, Liz Garcia. Liz has a ton of credits on both television and film, but we spent most of our conversation talking about her film work. She’s written and directed three features, with her next movie, Space Cadet, premiering on Amazon in July. She’s premiered work at Sundance and TriBeCa, and she’s a fierce advocate for younger women in the business. I’m an enormous fan of her work, and her as a person, and I hope you enjoy this wide-ranging conversation about show business, criticism, the creative process, and the pitfalls of seeking external validation.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Enjoy!

Liz Garcia: Oh, you have such a nice backdrop.

Eliza Clark: This is my office. It's not in my house, it's outside of my house.

Liz: Okay, so tell me…. as a person who works from my own house, even if it's to my own detriment, because I feel like I can't get it together to leave… what’s your routine for leaving for the office? Do you have to pack a lunch or something that will force you to leave the house?

Eliza: I don't have a routine. I should have one. But it's life changing to work outside of your home. I have ADHD so I can't go to a coffee shop if there's noise around me. I have to have my own office somewhere.

Liz: I can't have a little bit of noise. I can have nothing or so much noise that I can't pay attention to it. But half the battle of writing is where, when? What are the circumstances like? What are you wearing? Do I wear socks? That's a whole thing that I think about: do I wear socks? My feet need to be cold or warm, but it’s always different and it helps me concentrate if I make the right decision.

Eliza: That's great to know. I mean, actually, that dovetails into my first question, which is: what is your writing process?

Liz: When I first started, I was trying to become a screenwriter. So I was working as an assistant, and everything I was writing was in the margins, at night, or on the weekends. The urgency of that, the compressed time period that was available to me and the frantic desire to start my career… that was always the engine. I have Saturday afternoon and I'm gonna focus. And then I went right into writing for TV, where the structure and the process is handed to you. But once I started to do most of my writing at home, either doing development or writing features, I had to create a structure. I had to make it a Monday through Friday, 10 to 5 non-negotiable thing or I was plagued by guilt. I just couldn't make the decision every day: Am I going to write, or am I not? It just has to be: This is what I do every day. And even if I don't get anything much done, the routine and the effort keeps my muscles in shape, and it lifts some layer of stress.

Eliza: That’s what’s very helpful to me about having an office. I come to it every day. Even if I watch Vanderpump Rules on my laptop while I'm here, I'm still at work.

Liz: Process. It's part of the process. It's filling the well.

Eliza: How did motherhood change your creative process?

Liz: Well… I wanna be both encouraging and real about this.

Eliza: Be real. Be “rill.” This isn’t about encouragement. This, in fact, is a PSA against the dangers of writing unless you absolutely have to.

Liz: You know, once you have kids, you don't have the option of making writing your first focus and making it your whole life. When I became a parent, it was anxiety provoking for me to go from knowing that I could work at any moment to knowing that that was not the case. I would have to stop, not just to enjoy time with them, but to keep them alive and feed them. Sometimes I fantasize about… in my mind I've built up this character of the male auteur and I imagine him in his office with the door closed. I imagine his dutiful spouse taking care of everything. And of course this is a fantasy on many levels. But, as writer-mom you just don’t have that option of really shutting the door and saying, writing comes first, even when you're getting paid and you have a deadline. If your kid is sick, you gotta deal with that. If your child care is out, you gotta deal with that. You have to find ways to work around it. Some days it's simple. Some days you have an eight day work day, and you have childcare or kids at school, whatever. Other times I'm in the zone, and my kids come home, and I have to be like “stop talking to me,” and then I feel like an asshole.

Eliza: I think it's good for kids to know that sometimes they need to stop talking. I mean they won't do it. But I like to tell them every once in a while “Be quiet!” My kids like to sing twenty-four hours a day. It’s cute, of course, but they sing different songs. Also Zack sings all day long too. Three different songs, all at the same time. It’s maddening.

Liz: Did you find that once you became a mother, you couldn't tolerate overlapping sounds?

Eliza: It's funny, because my mom also has ADHD. And when we were little, she would say, “Auditory Overload!”, and we would laugh about it and be like man, Mom is so crazy. When she would be on the phone, we'd all have to be silent because we lived in a very small house, and we always joked that she was basically insane. But now I completely understand auditory overload. I frequently want to tell everyone in my house to shut the fuck up.

Liz: Yeah, like, don't talk to me. If the radio is on, definitely don't talk to me. If somebody else is talking to me, don’t talk to me, because I will feel a white hot rage.

Eliza: Early on, my creative process was always changing, very “when the spirit moves me.” Now I’m starting to understand that a little bit more as ADHD hyper focus. I'm a very cyclical person, so sometimes I'm in a period of very fertile creativity. And then I’ll have a long period of lying fallow and beating the shit out of myself about it. I used to sort of procrastinate, procrastinate, procrastinate, which was also part of the process. And all the ideas would build up over the procrastination period, and then I'd write something in three hyper-focused days. When I had kids, I couldn't do that anymore. Zack is such a involved parent, and for the last couple of years, especially when I was doing my show, he really was the primary parent so he gets to say this. He was like “It's your job, like you just have to do it." You can't wait until conditions are perfect. You just have to do it every day, and that’s it.

Liz: It’s true, but it doesn't make it pleasant.

Eliza: Do you enjoy writing?

Liz: I'm gonna say yes, but it's painful. The only thing that I'd rather be doing is directing, which is a field day compared to writing. It is just a cake walk compared to writing.

Eliza: I'm so interested in this! A really good friend of mine is a brilliant director. We were talking about this, and she put it so succinctly: “Writing is generative and directing is interpretive.”

Liz: Joey Soloway calls directing something like “receptive curating,” whereas writing feels to me like… Okay, so my least active favorite activity in the world is jogging, and I really try at this point in my life to not do it. But there were many points in my life where I thought I have to become someone who enjoys this free and available exercise. Writing often feels like jogging to me where I'm so burnt out, and it's shit that you just have to keep pushing through. You have to push through the discomfort. You have that antsy feeling like someone's trying to put a strait jacket on you, and you have to get the fuck out of here, but you can't get the fuck out because you have to finish the thing.

Eliza: Where do your ideas come from?

Liz: I’m sort of a magpie, I'm always collecting behavior that I like, or snippets of dialogue that are interesting to me or dilemmas. What sticks with me is what’s personal to me. I often don't realize it's personal. Like I just made this movie that's coming out this summer, that on its surface is very different from anything I'd ever done, because it's this big PG 13 comedy. My last two movies were earnest, edgy, indie movies. But then I realized that I'm always writing, even in a broad comedy, I'm always writing about people who are surviving grief. I'm collecting things that I'm interested in from life. But ultimately my creativity is just a need to process feelings.

Eliza: Where does that come from in your life?

Liz: My mom is a painter. My grandmother was a sculptor. It's not unusual in my family to pick art as a way of living. My brain is oriented toward stories, and I was born a deeply feeling person, but also very interior and private. So if you are both those things — you feel things really strongly, but you don't show them — you have to have some way of moving that through you. My life is very much about these cycles of moving out of sadness, moving out of melancholy, picking myself up again, finding hope, finding beauty. I think that's why my brain latches on to those stories. It's like, I know what it is to feel like there’s no hope. Maybe I’m writing myself a hopeful story every time I write on that theme. I mean, some of this is such a mystery.

Eliza: You don't know where things come from, and then sometimes you don't even realize what it is or where it came from until it’s done. When you're writing about things that you know are personal, or that come from your life in some way, how do you protect the people you love? How do you protect yourself?

Liz: I don't usually write stories that indict other people. But you know, I remember when I was trying to get my career going, and I wrote my first feature spec, which eventually became my second movie, One Percent More Humid — It was so revealing that when I finished it I was like: It's too bad I can never show this to anyone. I thought I can't have my reps read this, and look me in the eye. They would know too much about who I am and the way I live my life. But I’ve learned that's the only way to go. That script became hugely important to my career, because it was specific. I don't worry anymore about exposing myself. I would be more careful about writing about other people, I mean, I believe the Anne Lamott thing, “If they didn't want you to write about them they should have behaved better,” but when it's people you love…

Eliza: There is also the thing where people interpret your work and that's kind of not up to you. People can decide what they want to decide about what's happening, which is sort of where we dovetail into Judgment. What is your relationship to criticism?

Liz: After twenty years of doing this, I’m just much more divorced from criticism and outcome. But that had to be a journey, you know. I co-created a TV show in 2009-2010, and I was incredibly precious about every moment of that show, and how it turned out and I fought battles that weren't necessary, and that show got good reviews. So I didn't experience what it is to be eviscerated or misunderstood or whatever, until my first movie, which was The Lifeguard, It premiered at Sundance in competition. The reviews were mid to bad. This was a huge awakening, an important experience for me, because I went into it completely open and innocent. I did not prepare myself in any way for what it would feel like if people didn't love what I had made as much as I loved it. I mean, I was so naive. I was like, I love it. I put my whole heart into it. Really, people will at least see that I put my whole heart into it, and that will mean something. Maybe they'll pull punches. But that's not what people do. I previously had kind of an academic feeling about criticism like this is a valid form, this is an important part of the artist/audience dialogue, not realizing, of course, that only 1% of critics actually know what they're talking about and are thoughtful. Instead, you're gonna have all these, you know, second, or third string journalists talking about their feelings about your very female movie. It was hugely eye-opening to realize not only had I been naive, but on some level I still had this kind of student mentality of I am doing this work to please these people out here. I didn't know that I was operating that way until those people weren't pleased, until I made a movie that I thought was gonna change my career and it didn't change my career. And then I was like, Oh, do I care about lists? Yeah, I do, because I'm an a student. I had to adjust to the idea that I'm not a student anymore. I'm a grown ass woman, and by not achieving what I thought I was going to achieve, I had to really confront all my reasons for doing this and what was so important about it. I wish this for everyone who goes through this heartbreak: I realized that underneath any kind of desire for success, achievement, approval was something even stronger, which is just my desire to do my work. It was really good to get to the point where I knew for sure that even if no one ever liked my movies, if I had the chance to keep doing it, I would keep doing it. And that it wasn't for them. It was for me.

Eliza: It’s probably a bad thing to have your first thing be lauded. That must warp your relationship to praise, warp your relationship to the work. I mean, I'm sure it's possible for people to try to handle that, but I don’t know, I bet it’s hard. All artists, but especially young artists just starting out, have to be delusional. All artists harbor secret fantasies that when we, you know, give our heart to the public that the public will say, Oh, my God! A Genius piece of art! Life didn't begin until this existed! For that to actually happen to somebody would only fuel the delusion and ultimately probably lead you to stop growing. I think it's actually so important for us to feel the grief of putting something out there and learning the hard lessons. I mean, I love The Lifeguard.

Liz: Thanks.

Eliza: Lots of people loved it! But it's hard, when you're an A student and a perfectionist, and you're also used to pleasing people, to not just take in the feedback from the people that don't like it.

Liz: Well, there's another layer of judgment that is not just the critic’s judgment or the gatekeepers’ judgment. There's the judgment of working in a patriarchal business and a patriarchal world. Part of my heartbreak around The Lifeguard was realizing that even if I became sort of technically great, or even if I became the director I wanted to be, I might never get approval, because the system only allows a few of us who aren’t white men to enter the upper echelons. I saw very clearly in the reviews for The Lifeguard, not just accurate observations about what could have been improved, but also the critics’ bias toward women, toward beautiful women like Kristen Bell playing characters who had needs and flaws and turbulent inner lives. And, I had to accept the idea that critics may always be these people and they may never like what I make. So I can't afford to harbor any illusions of being part of the canon… but also what a fucking, ridiculous, audacious expectation! I had to accept that like I might not ever earn it, but even if I earn it, I might not ever get it. And then what? I'm just gonna keep making my work, because I'm so lucky that this is the way I participate in capitalism by doing something I love.

Eliza: I have many friends who have directed films. Every single one, including my husband, has been like “I learned so much from that first film, but there's so many things I would do differently now.” At the same time, film is a medium where lots of people only get one shot. Luckily for all the people that I know, they will all get more shots. Even if it didn’t turn out the way they imagined it in their heads, the work is objectively good, but you know what I mean? Especially if you’re not a white man, you get even fewer chances.

Liz: Yeah, absolutely. I feel so lucky just to have been able to make three movies.

Eliza: It's incredible. It's an incredible accomplishment.

Liz: It feels incredible because it's really hard. I know how we're looked at differently, and our stories are looked at differently, and we're not treated as legitimate authority figures who can handle big budgets or handle difficult actors. There’s so much working against us. As much progress as being as is being made, we’re still in this struggle. So I’m just trying to please myself and that’s hard enough. I mean, that quest will keep me going forever, meeting my own expectations.

Eliza: 100%. It's also the only thing that actually matters. After Y ended, I went through a period of feeling like I have no idea what's good. I thought this was good. I would watch this. I would enjoy this.

Liz: Right.

Eliza: So then I felt like I don't know anything. It took a long time. I'm finally in a place where I'm like, oh, I do know it's good, because I know what I like. Y was my first really big chance, and there were so many people I was trying to please. I feel more sure of myself now. You have to be the arbiter of whether or not it's good.

Liz: You kind of have no other choice. We've both experienced what it is to be dinged on something that we thought was great. And you've got to have some perspective that not everyone has the same taste.

Eliza: Well, some people have no taste.

Liz: Some people have no taste. It's this funny thing, because we're in this business where we're sort of chasing the approval of gatekeepers, we want to be hired by powerful people and work with powerful people, but then we also know that much of the work that is made is stuff we would want no part of. Are we chasing the approval of people we don't even respect?

Eliza: Then there's all these other factors that are beyond our control, which, you know, if your movie came out one year earlier, or one year later… If Y had not come out in the middle of Covid…

Liz: Different marketing. Yada. Yada, Yada, but that's just it. You have to be humbled to really see how little control you have over how people experience your work. You just can't control it, you're lucky to even be able to make the work. That's the one part you can control, is the making of the thing.

Eliza: It's why I care so deeply about the work environment. I wanna have fun making this. I want the people that I'm collaborating with to enjoy the process. That's all we have. What did that sort of creative grief feel like to you? For me, it was as if someone had died, and yet I kept feeling like this is so ridiculous. I was so mean to myself about feeling that way. I'm curious what it was like for you.

Liz: I felt personally rejected because I loved every second of making The Lifeguard. I loved every second of watching it, so I felt like if this was not received well by the industry, they are rejecting me personally. I was really hurt. I kind of had to keep working so I didn’t crawl into the fetal position and stay there. I just couldn't. It’s a similar process to accepting being a woman in the world. I might be in the wrong era, but what am I gonna do? I might never be taken seriously or seen in my full humanity. All I can do is just keep on keeping on… I had loved the process so much. You loved making your show right? So you want to do it again.

Eliza: Totally. I learned so much. I felt like, "I’m ready! I know how to do this now! I want to do it again!”

Liz: Yes. Exactly. You're burning up with let me do it again. Let me have a second chance at bat! I started to poke around about making another movie. There was an executive at a small division of Sony who was like, Oh, yeah, I liked The Lifeguard, I'll give you money for a movie. That was huge because I realized I had assumed that if a critic in the trades didn't like my work, nobody did. And it's not true. But again, I think that's this student/people pleaser mentality that elevates “People Who Judge” above their merit. It was amazing to realize people don't hate this. They don't hate what I have to say. That's not the case at all. I mean, they're not giving me 50 million dollars, but they are saying I'd like to see what else you can do, and that just made me feel like the luckiest fucking person in the world. Like if this is it, if I just get drops of money to make movies, this is amazing.

Eliza: So your experience of making your second film, what was that like compared to the first?

Liz: Well, there was a thing in my head that was like “This time they'll take me seriously dammit.” I was like no more pop songs in my movies. That was dumb. But the second film was a creatively, really wonderful experience. I felt like I knew more. There's such a steep learning curve with directing, and you only get to learn in this rarefied position of making a movie every few years. But I loved it, and it premiered at Tribeca. I had a second wave of releasing judgment around that, because this time I wasn't going to read any reviews. I started to realize it's not just about setting myself up for failure by trying to please people. It's also that I may have been setting myself up for failure by wanting to be important. I just somehow started to get this idea that's probably not gonna happen. That has nothing to do with me. All I can do is try to be the best at this that I can be. I may never be that great. I may never be seen the way I want to be, I have zero control over the meta of my career or reputation. And so there's no point in ever thinking about what is anyone gonna make of this. There's no point.

Eliza: Yeah, also, who is important is decided by whims. And you know…

Liz: Dudes.

Eliza: And dudes, but who do we make things for? Do we make them for our egos? Or do we make them to express something. I think I've come to terms with the fact that there was a lot of ego attached to my work previously and it didn’t serve me. Even if I get a great review! My most recent play, I got some good reviews, some bad, some mixed, but it’s hard not to only listen to the bad ones. And then, there was one review that was glowing, but I had to twist myself in knots to feel like it was a good review, because truly it made no sense. They loved the play, but they didn’t get it at all.

Liz: After twenty years in this business I never have expectations, so I don’t get disappointed. I really forbid myself the highs and lows. I compartmentalize. I hand in a draft and I forget that I'm waiting for somebody’s approval. But what it also means is, if if something good happens, I don't know what to do with that either. On some level I believe I shouldn’t take that in because it’s another kind of judgement.

Eliza: Yeah. It makes sense to not want to be too attached to somebody telling you it's good. But I think it's okay to take it in.

Liz: I guess I've also had the experience you're talking about with that review. I've gotten positive feedback on things I thought were mediocre. That's also fucking disappointing. You know, times when I've been like, I'm gonna do this kind of manipulative thing because I know people like it. And then everybody falls for it, and it's illuminating. If you please all the people you may be lowering the bar for yourself.

Eliza: There's a hard balance to be struck in being an artist, especially one who works in a popular medium like television or film. On the one hand, you have to be delusional, you have to feel like this is the most important thing in the world to even be able to get it on the page. At the same time, some of the people who are the most difficult to work with are the people who take themselves too seriously. It’s all about learning to take the outcome off the table. If you think you're gonna change the world, you are definitely not going to change the world. At the end of the day, we are not curing cancer.

Liz: You can't control how people perceive your work, but it’s also important to take the outcome off the table in terms of thinking about the finished product while you're creating it. That's something I really have to wrestle with, too. Every time I’m hired to write something or have told a bunch of people about what I'm gonna write, I shut down. I really struggle, because the minute I'm thinking about this as a script that's gonna land in somebody's inbox, I’m divorced from the creative process. So often, I’ll trick myself back into the process by writing a scene or two that is shocking. If I write a scene that is not what people would expect to be part of this, that might disappoint them or alienate them, it's a way of making the project my own again. That’s a little trick I’ll use: sometimes I'll start with a sex scene. I remember I was writing a movie for Disney, and I was really struggling because I couldn't stop thinking Will adults think this is funny? Will children think this is funny? Will teenagers think this is funny? And I ran into a friend of mine who's this very dry Swiss filmmaker, and I was explaining my anxiety to her, and she said, “What you need to do is: don't be funny.” It was perfect advice. Don’t try. Don't try to be funny. Just think about what the character would do.

Eliza: That's great advice, I love that idea.

Liz: A lot of us became writers because writing is where we put the secret private stuff. You have to bring some of that element of subversion to the writing, even when you're doing it as a professional.

Eliza: I'm gonna do that. I'm gonna do that today. Just write a bunch of sex scenes.

Liz: Do it.

Eliza: What does a typical writing day look like for you?

Liz: Okay. So I get my kids off to school, I come back home. I try to work out because I’ve learned that exercise is the only sure fire way that I won't be depressed.

Eliza: Same.

Liz: I try to work out and then I have to recover.

Eliza: I hope no jogging.

Liz: I've set myself free from jogging. I don't even go to a gym. I have an amazing trainer who works out with me over Zoom, and I have a bunch of equipment and I work out in my kitchen. But I work out really hard. So then I have to recover, which involves very slowly moving to the fridge and getting some food, very slowly showering, and then I set myself up at my desk, which is actually just a TV tray in my bedroom.

Eliza: Love it.

Liz: And I then struggle with not returning texts, not returning emails. In an ideal world, I would be completely disconnected from the interwebs and all of the outside world. But I'm not. I have two guinea pigs, two children, one dog.

Eliza: Guinea pigs!

Liz: Strawberry and Banana. They need to be fed in the morning.

Eliza: Sure.

Liz: My dog, Peach, also needs to be fed.

Eliza: Strawberry, Banana, and Peach! Oh, my God! A full smoothie!

Liz: Peach is always next to me when I'm working. So then, I have deadlines that determine like what the priority is, and I’ll try to get in the zone for writing. One of the recent writing hacks I've discovered is that I need to have a hood on.

Eliza: I love that.

Liz: Either a hood from a hoodie or headphones, but not playing music, just headphones that are… basically, I'm like a horse.

Eliza: You need blinders.

Liz: Sometimes I play music like jazz.

Eliza: No words.

Liz: No words, no words. Unless I'm really crazy and there's something that's due the next day, and I need to work for hours and hours. Then I’ll put on one song over and over and over, so I'm not paying attention to the words, but it's providing momentum. And I have like six beverages by me at all times.

Eliza: I call that The Drink Farm.

Liz: Yes, exactly. A seltzer, a caffeinated beverage, maybe a second caffeinated beverage, a lot of water. And then I'll work until I'm like Oh, my God, I need to eat food, and then I eat lunch. Usually the kids come home right when I'm when I finally hit my stride.

Eliza: Sure, of course.

Liz: And then I have to be like I care about your day, but I also want you to leave me alone and not speak to me. I try to work until the babysitter's done. I try to work until five, sometimes six. It's not writing straight that whole time. I take breaks to peruse the interwebs obviously. I wish for a day of eight hours of uninterrupted writing, but it's never that.

Eliza: I can't speak highly enough of an outside office. It's expensive, but it’s a write off. It’s worth every penny. It’s completely quiet. I have nothing else to do here. If I work at home, I’m looking around at things that need to be cleaned, laundry that needs to get done… it’s hard to focus.

Liz: That is definitely Mom Brain. Mom Brain has you saying I should be… I should be… I should be… and then you've eaten up all your work time doing this fucking household domestic shit.

Eliza: Yeah, domestic shit is a trap.

Liz: I'm aware of how hard it is to actually get into the zone of writing, and every time I have to get up and do something it's gonna take me another half hour to get back in.

Eliza: You have periods of time where your life is pretty regimented, where you are working regular hours, or you’re in a writer’s room, or showrunning, and it’s Okay, I have to take these calls. I have these meetings. I have to get this work done in this amount of time. And then, when that's suddenly over and you’re back in a period of having to be completely self motivated… it takes me a long time to get back in the groove.

Liz: Yeah, cause you're not in that in that heightened adrenaline state where you can easily switch into concentrating because you're firing on all cylinders.

Eliza: I'm starting to learn that adrenaline is bad for your body, but I really like it.

Liz: It is?

Eliza: Well, I think it's because there’s cortisol coursing through your veins. You get yourself into a highly stressed, adrenalized place. I mean, I love it, but it has consequences. This happened to me like a month ago, I was just writing so much I was in the Zone, and I felt so good. I wasn’t on anything, but I felt kind of coked up. The feeling is crazy. Not only am I like really good at writing, but am I also gorgeous?

Liz: I'm always chasing that feeling. That is, as you said, it feels like you're high, but it's just because you've had this hyper focus for a long period of time, and it's accompanied by elation and delusion, and it's just fucking great.

Eliza: While it was happening, I was like, this is going to end badly…

Liz: Does it end badly?

Eliza: Well, now my whole back and neck are fucked up because I've been so tense and writing for hours in one position.

Liz: Might I recommend Icy Hot?

Eliza: Oh yes, I’ve got Icy Hot all over myself. I probably smell crazy.

Liz: I work in a chair. It couldn't be worse for my back and my neck. But I can't concentrate If I'm at a desk with my feet on the ground. We're not normal people. My son said to me when the school year was starting, he said: I hate that feeling when you sit down in the classroom, and you look around and you realize I'm gonna be here with these people in this place for the next 10 months. I was like you're my son. I am totally phobic of repetition, sameness. It’s so boring, terrifying to me, and although being a writer sounds like a somewhat sensible job, the part where you’re chasing some weird creative high is not normal.

Eliza: Oh, it's definitely not normal. It's thrill seeking. I don't want sameness, and if I get into a place where I'm getting too much sameness, I will get itchy and I'll start to feel really depressed.

Liz: I don't have a lot of, I guess, serotonin. So I think I'm always looking for the elevated state. Escaping into the world of your script is an elevated state.

Eliza: So I want to read you a quote about Judgement, the Tarot card: “Judgment signifies a moment of reflection and evaluation. This card asks for a critique of past actions and objective understanding of self.”

Liz: Oh, that's interesting, cause that's bringing up the idea of healthy judgment and having healthy perspective. I struggle with this, because I, for instance, would rather gouge my eyes out than watch one of my movies or episodes of TV. I love them while I'm making them but I don't like to revisit. But isn't it important that we have some clear-eyed understanding of where we need to grow instead of what I definitely have, which is like a nebulous, frantic feeling of needing to be much, much more, and do much, much more.

Eliza: How do you look at old work? You said that your second movie was a script you'd written when you were younger, right? How was the process of being in communication and collaboration with a former self?

Liz: Yeah, that was wild. So I wrote One Percent More Humid the week I turned 25, and then I didn't direct it until I was 39. My feeling in picking the script up to finally direct it was that it was very, very true to that time in my life. It was true to being 25, I was writing about characters who are around that age. It's strength was that it was so honest and authentic, and I wasn't going to judge it, or I should say I was so aware that the judgments I had of it came from the perspective of an older person who was judging the characters and worrying about them. In order to do justice to the movie, I needed to not touch a script that had been written by a 25 year old. I really didn't mess with it at all. But that was kind of a special instance, because of that time divide. I don't know what it is about looking back at past work. But even something I've written a month ago feels cringey to me, maybe because we write in this elevated state. We write with a part of our brain that isn't the judgment brain, that’s more free and more earnest. Then, when you pop out into the other perspective it's going to be kind of embarrassing.

Eliza: I imagine that when you were directing that movie, it felt like you were directing someone else's script.

Liz: Yeah, in a way it did but it felt very personal. So in that way I felt kind of exposed. But you eventually reach the point in your career when you're not precious about your words. That took me a while. I do script coaching and teaching, and what I run into a lot is that people are precious about their words, because deep down, they're afraid they don't have any more. When you've done this for long enough, and you've been forced to just iterate and iterate and iterate, you realize it's gonna be okay. I can cut this. It's gonna be okay. I can think of another way to stage this. I can think of another way to say this, it's gonna be okay, because I'm not a well that will dry up.

Eliza: You have to have faith. I don't know about you, but every single time I'm done with something and start something new, there is a short period of time in which I forget how to write.

Liz: Oh yes!

Eliza: There are no more words. I've used them all, I need a new career. Maybe I’ll become a children’s birthday party planner. It’s a process, but it happens every single time.

Liz: I'm so glad that you're saying this, because it happens every single time to me still, after all these years. My friend and I confessed to each other recently that when we start a new job, we always wind up googling: how do you write a script?

Eliza: Everybody does that. Yeah.

Liz: I don't know what that is! It’s like I have to break down the entire car and go how was this made? I have to watch movies and be like, oh, that's right, that's what an act one looks like. It's ridiculous!

Eliza: My favorite thing actually is to watch something that is not great, but not so bad that you want to turn it off. I find mediocre art very inspiring. I'm like, Oh, okay, I can do this, if this got made, I can do this. I have great respect for the process, and also, I understand how much goes into something being mediocre, nobody ever sets out to make a bad thing. But it is really nice when you watch something and think: Okay, I can get through this, I could do this.

Liz: A huge part of what gave me the confidence to say that I wanted to direct was working in TV with so many directors and just realizing that there are very few people who are actually geniuses, and sure, those people are really inspiring, but everybody else is just a person doing it shot by shot, scene by scene, exactly like the rest of us do it.

Eliza: And even the geniuses have their missteps.

Liz: Yeah, you're right about that. And that's important to remember. Not that I'm aspiring to genius. I'm just aspiring to continue to get slightly better each time, that's all.

Eliza: I actually think that being a genius is a curse. I imagine genius feels out of your control. The feeling that you're channeling something that's from somewhere else is a great feeling, but it's also scary, because it feels like it's sort of beyond you.

Liz: I would love to have that feeling the next time I make a movie.

Eliza: I imagine that's the constant feeling of genius. Where people are like, “Wow, how did you do this?” And you maybe don’t even know. I know that I, as a non-genius, have to put one foot in front of the other, and there will be a period of time in which I'm gonna feel like shit. And I'm gonna feel like this sucks, and I suck and everything sucks. But I also know I’m resilient enough to get through it. And usually once you do that, you're like, Oh, this isn't that bad. And then like a little later, you're like, No, actually, I think I like this, or even: this might be good.

Liz: It might be good, it might be decent.

Eliza: Okay, one more Judgement quote: “Judgment also signifies a reawakening, a refined sense of direction, a positive change that affects the future outcome.”

Liz: That makes me think of my experience just being a fan of the medium, like my best moments are when I'm watching something that somebody else made, and I love it so much. And I'm so excited about what I'm seeing. Or I realize I learned something I can change about my approach. I would say 50% of the time those realizations for me are cannabis augmented.

Eliza: Nice.

Liz: I believe in that. It’s been helpful to be an ardent fan of movies and TV and marijuana. It all goes really well, together, actually.

Eliza: Well, part of what's great about pot is it’s sort of just like being in the Zone when you're writing or in the flow. It takes you out of the critical part of your brain and puts you in a more receptive place.

Liz: A more receptive place and for me often a more visual place. Particularly for directing, I’m seeing things that I didn't see before. I wish I could spend every single day getting high and watching movies.

Eliza: Essentially what I did in college.

Liz: Will we ever go back those days? Retirement, maybe.

Eliza: Old age. Yeah, sure.

Liz: Yeah, yeah, that sounds fun. Empty nesters.

Eliza: I've started to realize that this whole newsletter is kind of about creative grief and generally about the creative process. Do you have anything else you want to say about that?

Liz: Just that heartbreak is inevitable in this business and it’s disorienting and awful, but be glad when it happens because you’re getting it over with. I'm so glad that I no longer have illusions about what it would feel like when everybody finally approved of my thing. Now I know that as long as I like it: that’s all that matters.

Eliza: Totally. What's the movie that's coming out this summer?

Liz: So it's called Space Cadet. It's basically “Legally blonde" at NASA Astronaut training camp. And it's coming out on July 4th on Amazon Prime Video, baby.

Eliza: I cannot wait to see it!