Five of Cups

Special Early Edition! A conversation about grief with writer Lily Diamond.

Five of Cups Playlist

The five of cups is a card about grief, traditionally an emotion and experience that I desperately avoid. Denial of grief was baked into me early, masquerading as optimism. If you always try to “see the glass half full,” sometimes the only way to do that is denial. Sometimes the glass is not half full. In fact, occasionally the glass shatters in your hand and you’re covered in blood, exposing muscle, tissue, sinew, and bone.

As you’ll see in the conversation that I had with my friend, the brilliant writer Lily Diamond, I’m still figuring out how to feel complicated emotions like grief. There have been so many times in my life when I have mistaken grief for shame or fear or anger. Lily, on the other hand, was forced to confront the soul-defining work of grief in her young adulthood, and her honesty, vulnerability, and insight really blows me away.

Lily and I met in college when I produced a production of Euripedes’ Medea, directed by our brilliant mutual friend Ben Evans, with dramaturgy by Lily. Medea is a play about vengeance, passion, power, and the horrifying violence people are capable of when they let their emotions run amok. The play was written in 431 BCE and still somehow resonates. The plot is essentially: Medea’s husband, Jason, leaves her for a younger woman. Medea and her sons are exiled, and in her grief and rage, Medea kills Jason’s new bride, and then kills her own children to punish Jason and take her revenge.

Medea also explores the grief of being a woman in an ancient time, beholden to the laws of men, powerless over the appetites of men, stripped of value by the whims of men. Killing your children is never a good look (and you can quote me on that), but Medea is a woman in 431 BCE, and there aren't many options for her. Here’s one of Medea’s powerful speeches about being a woman:

Of all creatures that have breath and sensation, we women are the most unfortunate. First at an exorbitant price we must buy a husband and master of our bodies. [This misfortune is more painful than misfortune.] And the outcome of our life's striving hangs on this, whether we take a bad or a good husband. For divorce is discreditable for women and it is not possible to refuse wedlock. And when a woman comes into the new customs and practices of her husband's house, she must somehow divine, since she has not learned it at home, how she shall best deal with her husband. If after we have spent great efforts on these tasks our husbands live with us without resenting the marriage-yoke, our life is enviable. Otherwise, death is preferable. A man, whenever he is annoyed with the company of those in the house, goes elsewhere and thus rids his soul of its boredom [turning to some male friend or age-mate]. But we must fix our gaze on one person only. Men say that we live a life free from danger at home while they fight with the spear. How wrong they are! I would rather stand three times with a shield in battle than give birth once.

In the conversation that follows, Lily talks about her grief in the wake of her mother’s death, and the earth-shattering identity shift that followed. We also talk about the many different forms of grief, that all-encompassing, wily shape-shifter. We live in a culture of suppression and denial, because capitalism has no time for grief.

The violence of our world — genocide, gun violence, domestic violence, mass shootings, transphobia, the stripping away of our rights to bodily autonomy, unchecked greed that ravages our planet, the end of democracy — must be faced head-on. We have to learn how to grieve, or we’re going to keep on killing our own children to hurt the people who hurt us.

Lily is brilliant, insightful, vulnerable, and brave. I love her writing and her brain, and I know you will too (I’ve included links to her work after the interview). Enjoy!

Eliza: What is your relationship to grief?

Lily: Well, the timing of this conversation is very poignant. Yesterday was the 16th anniversary of my mom's passing. I didn't even really clock that when we scheduled this. Today is the solstice and it's a Thursday. My mother died on a Thursday summer solstice. A lot of comings together in this little day here.

Eliza: Wow.

Lily: I’m thumbing through this book about grief that I love so much because I want to talk about it as we go through this conversation. It's called The Wild Edge of Sorrow. It's by a psychotherapist named Francis Weller. Has this ever crossed your path?

Eliza: No, but historically I avoid negative feelings like the plague.

Lily: A friend of mine, who we also went to college with, gave it to me in 2018. She was reading it and came to visit and was really vocally recommending it to me. I felt sort of scared and annoyed in the way that happens when someone is recommending something that's too on point.

Eliza: Where you're like, I’d rather not right now, thanks.

Lily: Exactly. I was like, no, I don't want the fucking book on grief. I’m also now seeing this, this is hilarious, there are two stickers over the ISBN code. One says “amazing,” and the other says “so proud of you.”

Eliza: That's cute. Encouragement for reading!

Lily: I actually have never finished reading this book, which is, I don't even know what to say about that. So I bought the book eventually, or maybe she left her copy with me. I have since gifted this book to so many people. It’s my knee jerk send when someone is going through a big transition. Francis Weller’s take, his vision on grief work, is that we are all going through loss of some kind all the time. He outlines these five gates of grief. He calls them gates as in portals that we all move through, you know, transitional spaces. This framework was so helpful for me.

I lived a lot of my life accompanied by a kind of melancholy that predated my actual experience with real loss. Some of that was mythological longings and identifications, and feeling different from the people that I lived around, and various forms of otherness I lived with growing up. And then there are weird coincidences, like my absolute favorite movie of all time is Contact.

Eliza: I love that movie.

Lily: Incredible. I try to watch it every year. I'm actually about a year and a half overdue. So I really need to get on that. I watched it in the theater when it came out in 1997. I was 13, and I went back again and again and watched that movie like seven times. I would sit there and just weep. It's funny when I tell people about this, because they're like, Oh, you're a real sci-fi buff. And I'm like, No, definitely not. Something else was happening which was fundamentally… Carl Sagan's work is really about the loneliness of being human in the universe, struggling with what that means when we come face to face with that loneliness. It was not until my mom died, like ten years later when I was 24, that I realized, Oh, my God, that film is actually about… It's about this scientist who's an orphan, who lost both of her parents. So much of the film, especially the first part, is her wrestling with both her mother and her father's death, and really trying to locate that loss within this larger worldview and scientific quest for connection in the universe, both in outer space and on earth.

I think about all of these pieces, and some part of me is like, was I somehow preparing myself for this thing that was about to happen? My mom was very healthy, which was part of what made losing her so hard. I’ve thought about that in the years since, because it seems so odd, my fascination with Contact. I didn't do that with any other film.

Eliza: The Universe knew you would need it.

Lily: It was teaching me or giving me something. I felt connected to it in a way that helped me feel seen. Grief has taken so many different forms in my life over the years, has been such a brutal teacher and a constant companion. Being able to think of it, not in the Elizabeth Kubler Ross model of the stages of grief, but really looking at what are all of the different kinds of grief that we are all living with always? If we were willing to be honest about these forms of grief, these different gates of grief that we all pass through, what kind of a world would we live in? How might we be able to show up for each other in ways that are far more generous and connected and honest than we're capable of now?

Contact. Watch this and try not to fall in love with Matthew McConaughey, I dare you.

Eliza: I'm really interested in the different forms of grief, particularly creative grief. There are a lot of words that come up. Loss. Disappointment. You can grieve an idea. It’s also worth noting that our society, particularly our American capitalist society, is not designed to allow for grief beyond a certain threshold. We account for acute grief, but only within a small window of acceptable time. I have experienced grief in my life, but nothing like what you have experienced. Even so, I suspect that almost any grieving process is circuitous, ongoing, and non-linear.

Lily: Totally. What was really unique about losing my mom was that it happened in stages. The first, and in some ways the most cutting stage was my mom’s diagnosis and the fact that it coincided with a very significant breakup. I was living with a romantic partner, my boyfriend at the time, and our lives were deeply intertwined. We were teaching together. I had moved to Michigan. I was living there with him. He ended our relationship a couple of days before I flew back to be with my mom when she had a hysterectomy. In that hysterectomy they discovered a very late stage cancer diagnosis. It was this double whammy of free fall, really of everything that I thought I knew about my life. I was only 23 at that point. I was very young.

Eliza: That's identity shattering.

Lily: I was really young, but I was also really sure about who I was in the way that you can only be when you're that young. I was like, I'm gonna be with this man forever, this is my life. This is who I am. I was still in this unindividuated state with my parents of everything they do is the best way to be. My mom was an aromatherapist and an herbalist, and she prided herself on how she cared for herself and her body, and she had an impeccable diet. Didn't drink. Didn't eat sugar, caffeine… all of these things that you think add up to eternal life.

Eliza: Right.

Lily: Up until then I had adopted a lot of punitive, New Age ideology that is very moralizing, a lot of superiority complexes around ways to be and think and live. I thought that those were the answers. It became very clear very quickly that these might be the answers for somebody, but in this case it hadn't panned out. Those two initial losses, this romantic relationship that I had thought of as being something that was going to be a part of my life for a very long time, and was really identity-forming because it was also connected to my work, and then my mother's diagnosis—this acknowledgement of parental fallibility and mortality. The later loss itself, her actual death was… It's a whole other thing, but those two first losses were very significant.

Eliza: It sounds like you grew up having no doubt that your mother was the picture of health. In a way, when she's diagnosed with cancer... that's kind of like finding out there is no God.

Lily: Absolutely. It took me a long time to unwind a lot of those pieces. At the time I was teaching yoga, meditation, and a lot of Hindu and Buddhist philosophy and practices, and so much of that was also about establishing worldviews, not just for myself, but also delivering them to other people. Starting about six months after my mom passed away, which was a year and a half after her diagnosis, I started to hear this voice that was clear as a bell. The moment that I would go to start teaching the voice just said, Stop teaching.

Eliza: Whoa.

Lily: And I was like this is so inconvenient. My body was also rebelling, I was in tremendous pain. But I was only in pain when I was doing yoga asana.

Eliza: Your body was speaking to you.

Lily: My body was like, Get out of here, stop. There’s something here that is not honest. And there were a lot of forms of psychological and spiritual and emotional abuses that had been a part of that whole mix. My experience in that space intersected with the kind of spiritual bypassing that I saw my mom do through her illness.

Eliza: Can you tell me a little bit more about that?

Lily: For people who aren't familiar with it, spiritual bypassing is such a helpful term for anyone who dabbles in spiritual thinking. It’s a way of bypassing the difficult or messy truths that we come across, or the things that make us uncomfortable, by sublimating and dismissing them…kind of like gaslighting yourself: yes, I may be deeply traumatized by something that happened in my childhood, but, for example, “what's past is past,” “Let go and let God.” I made an Instagram post about it, with all the different kinds of spiritual bypassing that people do. Spiritual bypassing is also connected to toxic positivity. In my mom's case, she did not want to even think or have the word “cancer” be spoken around her while she was dying of cancer.

Eliza: Was she undergoing treatment?

Lily: The doctors suggested a course of chemo and radiation, and she decided not to do them. She was certain that they would kill her faster than the cancer. She said that she would do them if this long-time family physician, who she trusted, looked at the data and could tell her that there was a 50 percent or more success rate for that course of treatment. Now I know that is an insane success rate.

Eliza: Right.

Lily: Like, if there were a course of treatment for cancer that offered someone a 50% success rate, everyone would do it, like that's just bonkers.

Eliza: She was diagnosed with terminal cancer?

Lily: It was Stage IIIC endometrial cancer, and it had already spread to her lymph system. I can’t remember how much time they said that she would have if she didn't do treatment. She ended up going to Switzerland and doing this other homeopathic oncological treatment, which, by the way, was also extremely rough on her. It was not some gentle, easy breezy thing. I had this wild privilege of watching this person who, as you said… I really took her life as this blueprint for how to be and how to live as a kind of religion. I watched her wrestling with all of these guideposts that she had set for herself, ideologies that she had chosen to look to, and I got to see what it looks like for someone who has done a lot of spiritual potpouriing to encounter the end of their life. What beliefs are you going to choose to keep when you are at the end?

Eliza: Right, when you are faced with the reality of your death.

Lily: All of the different systems have very different things to say about end of life.

Eliza: What did she land on?

Lily: I mean it was within the general potpourri. My mom and dad had both explored and been active practitioners of Buddhism. As she was dying, she was reading The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Tibetan Buddhist practice lays out very specific practices for what happens to the body after death. My parents, by their family background and genetics are both Ashkenazi Jews. But both had fled their religious backgrounds and, honestly, their families in a lot of ways. They met on Maui in the ‘70s and ended up living here, which is where I grew up, and they were very content to be very far from the ideologies of their family and their youth. My mom ended up coming to the middle. She was like, well, I don't want my body left for like seventy-two hours, but I’m okay for it to be left overnight. So we left my mom's body overnight and called the coroner the next morning. That was her wish, to allow for the mindstream to take leave of the physical form and be ushered into its next incarnation before her body was taken.

Eliza: Were you with her when she died?

Lily: I was.

Eliza: What was that experience like?

Lily: It was one of the most harrowing experiences of my life. Her death process was really hard. About three months later, I attended my first birth. One of my best friend’s births, which was unmedicated and at home with two nurse midwives. I do not think I would have been okay with everything that happened… as in, I think I might have at some point gotten really scared for my friend, or really scared for myself, or really scared for humanity, that this is what has to happen in order for us to continue… if I had not been with my mom when she died. What I saw happening with both of them was so similar, my mom was fighting to die the same way that my friend was fighting to give birth.

Eliza: Have you written about this?

Lily: I wrote a book about my experience with my mom dying and the identity crisis that ensued. That was the first book that I wrote. I finished it in 2011. Chapters of it are published, and a lot of parts of it ended up in my first published book, but big chunks of it have never been published. At some point during the pandemic I realized I just have this book sitting in my desk like, I'm sure you have screenplays like this… So I was like, why don't I just share it with my agent? See if it's just an immediate yes, why not throw it out into the world? So she read it. There were ensuing conversations about how difficult it is to publish memoir as a not-wildly-famous person. But she was also like to be honest, this was unbelievably painful to read.

So the book that I'm writing now is a novel. The protagonist is based on me. Her mother has also died. In the memoir, my mom's death takes up a whole chapter. It's a whole big thing. Of the actual deathing process.

Eliza: Sure.

Lily: But when I was writing the novel I was thinking a lot about the placement of the death in the book, thinking about what the reader of this book can handle, what they need at this juncture. I kept winnowing it down, winnowing it down, winnowing it down. And finally it got to a point where it was one paragraph. And I was like, you know what? That’s correct. After my agent read it, we were talking and she was giving me feedback. She was like the mother's death was so good, and I was like I did that for you. I had your voice in my head the whole time.

This goes back to this question of How much death can we handle, as a culture right now? I don't know that I could have written it that way if I weren't so far from her death.

Eliza: You've processed it for many years now. You wrote this incredible piece about leaving the wellness space. So many forces converged on you at once. I wonder if you could talk a bit about what grief had to do with shaping your identity or unshaping and reshaping it.

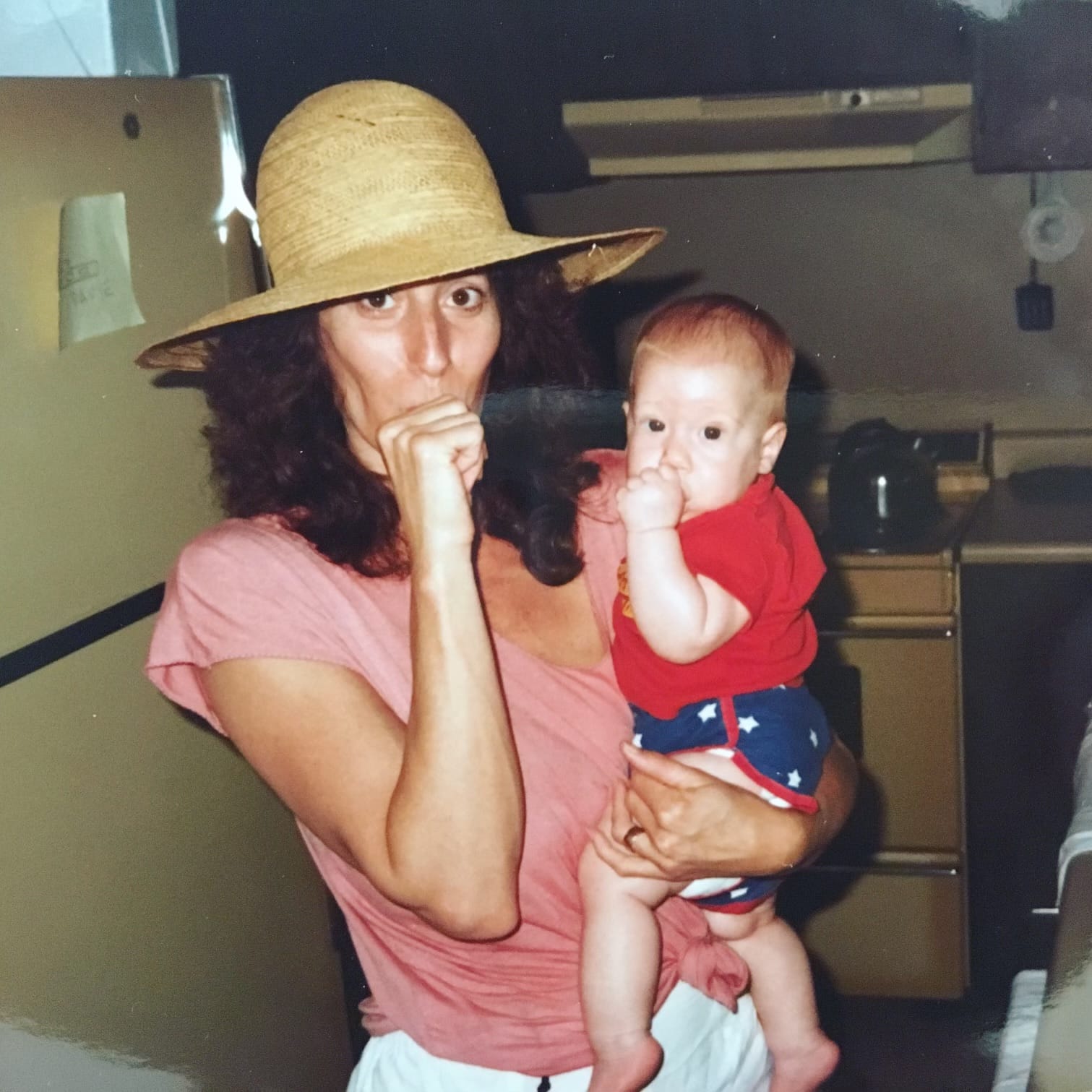

Lily with her mother.

Lily: I would love to share with you the five gates of grief so that they can inform how we talk about this, because they’re so powerful, and so valuable in thinking about how we approach each day, the little annoyances and challenges and frustrations that we face, but often don’t really engage with as losses…

Eliza: Please share them with me!

Lily: The first gate is: everything we love, we will lose. This includes the kind of losses that we think of generally when we think of grief and loss: family members, pets, homes, places that burn down, injuries, illnesses, all of these kinds of things. The second gate is places that have not known love. These are losses of shame, places in ourselves that ache to be acknowledged and loved but have never received that, the places that we have denied or rejected in ourselves. I’m also thinking of Internal Family Systems work, Richard Schwartz’s work. The parts of ourselves that we exile. The third gate is the sorrows of the world. This takes into account, obviously, the absolute horrors of the world, the great griefs of war, famine, and also, environmental loss. He takes into account the weight of understanding that we live on a planet that is in crisis, and what that loss informs in us. The fourth gate, which is one of my favorites and touches perhaps on the creative grief you were talking about… what we expected and did not receive… which is just like Oh my God.

Eliza: Whoa. That one.

Lily: So gutting. This touches on so many things for me, big life pieces. Not just professional and creative life, but also wanting and not yet having a romantic partner, wanting to be a mother in a certain way and not yet having my life circumstances align with that. And then I just love the sort of quotidian nature of this one, too, of just acknowledging that every day I wake up and expect something that I don't receive.

Eliza: The daily grief of being alive.

Lily: Totally. Every single moment of it. And then the fifth gate of grief is ancestral grief, both acknowledged and unacknowledged. Sorrow from our ancestors, from lost connections to home, ways in which we have inherited and carried forth ancestral trauma, collective griefs that may come from within our family lineages.

Francis Weller does these grief rituals where he allows people to connect with and explore each of those gates of grief. I have not personally attended one, but just getting to explore my own experiences through that lens… It really normalizes grief right? Immediately it doesn't feel like, Oh, I have to have experienced some kind of outsized loss that irrevocably changed everything about my life to experience grief. There are these losses that really shaped me and changed everything about my worldview. But we're living in a time where we are touched by grief daily — personal grief, collective grief, environmental grief, societal grief. These losses that I think we often barely know how to even articulate, let alone handle and process. So much of my work and my writing is about, okay, how do we normalize this?

How do we make living with grief something that is not extraordinary? It's just really the day-to-day tidal wash of being human.

Eliza: Maybe the acknowledgment of grief allows you to feel even more alive. Grieving acknowledges your human life.

Lily: Absolutely.

Eliza: To go back to what you were saying before… your mother was diagnosed and three days before that your boyfriend broke up with you. How did that change the way you grieved and processed the breakup?

Lily: It made me so much angrier at him.

Eliza: I'm sure.

Lily: It became he did this thing that I didn't want him to do, which was end our relationship. Even though I was super unhappy in the relationship: the break up was not happening in a vacuum. But I was like, we're gonna figure this out and soldier through. We're 23, and this is forever. And then it became, wow! You're a horrible person! You are abandoning me in this moment in my life when I need you the absolute most. I remember my dad, and maybe my mom though she didn't show it, being really annoyed with me that I was so upset about this other heartbreak when I should just be focused on the medical emergency that we needed all hands on deck for. I remember my dad at one point saying, Well, you know, the silver lining is that it made it easier for you to come back and help care for your dying mother. I was like, not a great silver lining, sort of a terrible silver lining. But thanks for the spiritual bypassing.

Eliza: You are such a deep thinker, such a creative person, and you also seem so… embodied. Do you feel connected to your body? I’m not sure what this has to do with grief, but it’s something I’m interested in knowing…

Lily: I see you as very embodied, too.

Eliza: I'm getting better. Quitting drinking helped.

Lily: I have always felt a super strong body connection. I've also always had a weird, quirky kind of grief connected to my body. It definitely was not what I expected it to be. I was born with congenital bunions and flat footedness. The first podiatrist that my parents took me to was like she needs leg braces, she'll never be able to run… I was three. My parents were like goodbye. They were like Nope, and went to a different doctor who was like, no, she doesn't need leg braces, we’ll get her orthotic inserts. I was the kid on the playground in Hawaiʻi when all the kids are barefoot, with blazing white skin and red hair, wearing high-top Velcro sneakers, and orthotic inserts. This doctor also said, have her start dancing. It'll strengthen her arches. So that's what they did. I wore orthotics and I started dancing, and I danced all the way through high school. Dance is still a really big part of my life, which is part of why it makes me so happy when I get to see you dancing. Or dance with you!

Eliza: I'm a real dancer…

Lily: I also spent a lot of my life connected to this rigid worldview of the Wellness Industrial Complex, and hetero-patriarchal society's idea of the ideal woman's body… My parents were very hard on me about my weight, my appearance…

Eliza: I'll just say, this is not the point, because what you look like doesn't matter, but I think of your body as the ideal woman's body.

Lily: My gosh.

Eliza: I do.

Lily: I'm gonna get that tattooed on my face: Eli Clark once said…

Eliza: Interesting that your parents came from this hippy mindset… I mean, you were born in a commune, and they were still hard on you about your body…

Lily: They were very, very health-obsessed—with the definition of health existing within a very rigid set of boundaries.

Eliza: So it wasn't necessarily about like the male gaze, but it was about health…

Lily: But also it was the male gaze, because I was super frustrated that I didn't have a boyfriend, and the answer was always like maybe lose 5 pounds.

Eliza: I relate to all of this.

Lily: If we're looking at these gates of grief… the second gate, those exiled or shamed places in myself… and then also that fourth gate of what I expected and did not receive in relationship to my body, I was feeling these very early kind of failures. But the treatment that I had, the orthotic inserts and the dance strengthened my feet, and I'm very grateful not to have pain like a lot of bunions. A lot of dancers have bunions that are extremely painful that come as a result of dance and overwork. I trained with ballet classes so that I could have the technique to do other styles, but there was never a question of Am I gonna be en pointe, or anything like that, which I'm very grateful for. That was a huge blessing cause it just removed that whole world of competition from my life. And I don't have pain, knock on wood, associated with my feet, so the thought of potentially getting surgery to aesthetically correct the bunions—which I sometimes think about because I’m still absolutely self-conscious about the way my feet look… I have these moments where I'm like God! What would that feel like to not look down and see myself marked in this way? But it's not worth it, so many people have complications with these surgeries, or the bunions grow back. Nope, just gonna keep the ol’ bunions.

Eliza: I’m realizing as you're speaking, that I am currently in this exact grief process, I mean not about bunions, but about my body, and my expectations versus reality. A lot of that comes from having been a child actor. It created extremely unrealistic expectations of what I should look like. This is kind of blowing my mind.

Lily: It's so real. It is so daily and so immediate, always. Right? I have carried this very close relationship to my body into grief. But also I'm someone who takes a tremendous amount of pleasure in my body and in the senses, the sensorial experiences of being human. That's something that's very important to me. And in the somatic work that I've done, I've always also been interested in the psychosomatic components. I remember the last really big breakup that I went through, there was this period after where every time I worked out I would just start sobbing. It’s very hard for the body to lie. When you're really working it out and really moving, I find that stuff comes up. Whatever is latent is going to be jostled to the surface.

Eliza: How did you get through that? You just cried through your workouts and called it a day?

Lily: Yeah, I mean, they were squalls, you know, passing squalls.

Eliza: I have a really hard time recognizing emotions as passing squalls. I am a deeply cyclical person chemically. I have high highs and low lows. Anytime I'm feeling super depressed, I'm like, well, this is it. This is the rest of my life. Everything is worthless, everything sucks. And then I'll also have periods of some light mania where I'm like Yes, this is how I'm gonna feel forever! I watched Inside Out 2 last night with my children. It's kind of incredible.

Lily: I can't wait to see it. I loved Inside Out so much.

Eliza: It's kind of a master class in the human brain. You're such an intelligent person. I’m fascinated by the mix of your hyper intelligence, and some of these more maybe woo woo or spiritual beliefs. You’re not the kind of person who's like this crystal is gonna change everything. Your witchiness is well earned and backed by facts. I don’t know if I have a question. It’s just something I admire about you.

Lily: Thank you. If I had magic powers I would now do some sort of special transformation!

Eliza: A flourish! Turn into a cat or something.

Lily: The spiritual work ultimately… and honestly I cringe at this point even using the word spiritual.

Eliza: Yeah, sure, we all do.

Lily: Also the word “work.” So we’ll just have to, I don’t know, put both of those words in quotation marks. The “spiritual” “work”… There are monastic practices, and there are tantric practices. The monastic practices are about taking yourself away from the world, doing your practice in ways that remove worldly distractions. The tantric approach is about being in the world and engaging in practices that are directly immersing you in the dirtiness, the grossness, the grief, the mania, all of it, and saying learning to be sane amidst all this is what will also get you free. My interest is much more in practices that keep me in the world, that allow me to see the pieces of my life as opportunities to be more honest with myself. That’s really about being able to understand, as you said, that both the low lows and the ecstasy of light mania are transient.

Eliza: But then I start to wonder, and this is where Inside Out 2 comes in… what is the self?

Lily: Right. What is the self? And why have the experiences that we have? Even spiritual bypassing, or someone who just doesn't give a fuck about talking about grief… it’s like, Okay, fair. Because what are we doing here? We only have so much time. At the end of the day, what we know is we all have converging sets of human experiences that involve loss, joy… each of these very pivotal or life-defining realities are parts of being alive. We have to somehow cope with them, not just within ourselves, but maybe even in more difficult ways, with each other. I mean, that’s the real problem: other people.

Eliza: There's friction between all people all the time, that's where a lot of conflict comes from — that portal of expectation versus reality. Insecurity, imposter syndrome, egos lashing out. And collective and ancestral grief… those feel spiritual to me. Those are evidence of something more, maybe of a collective unconscious. When the world is really scary, as it has consistently been for basically my entire life, my friend always says, I don’t think human beings are meant to know every horrible thing that’s happening in the world all at once. It doesn't mean that we shouldn't know it, or that we shouldn't face it. But it’s a question I’m always asking myself — what is our responsibility as individuals to hold collective grief? And what is your responsibility to the people who rely on you every day? Is it necessary to keep even the thinnest barrier between you and the horrors of the world so that you can cope with daily living?

Lily: What is our responsibility to other people? My most recent book, the What’s Your Story? Journal that I created with Rebecca Walker… The In Community chapter really digs into a lot of questions about this. What do I believe my responsibilities are to the people around me, and what responsibilities do I want the people around me to hold towards me? The answers to these questions are continually going to shift and change, depending on needs, seasons, realities. But I think there is some kind of fundamental question in terms of just one basic developed zygote to another basic developed zygote: What do we owe each other as fellow humans?

And through the lens of grief, when we experience or perceive other people’s suffering, what is it, then, that we owe them? What does it reveal to us about ourselves that is both unbearable in that it makes us want to look away, but also common in the way that it forces us to stay present and want to do something about it?

Eliza: This is what I think about all the time.

Lily: I don’t want to put words in your mouth, but I think we both feel that the act of writing and storytelling is an answer to that, but sometimes it feels too easy. Yes, I can say something meaningful, I can write something, I can share it, maybe it will move people. It could change the way that people think. But then the question of risk emerges. Is the risk involved enough to merit feeling like I have made a difference in some way?

Eliza: I have exactly the same feeling, so you can put those words in my mouth if you would like to. I enjoy making art, so does it really count as doing anything? That also speaks to a capitalist work ethic. If I enjoy it, it must not really be work. Deep in the recesses of my body exist a bunch of core beliefs that I am trying my darnedest to undo. What is the value of art? What does it actually do? But then you think about you watching Contact once a year…

Lily: Absolutely.

Eliza: And it's meaningful. Ancestral and epigenetic trauma, ancestral grief… All of these things speak to me about a connection to something greater than ourselves, a higher power, a higher consciousness. It’s not just: Oh, this bad thing happened to my parent, and so they parented me in a certain way that I feel that trauma. The ripple effects can be felt for generations. It’s nature and nurture. Also, the things that happen to us live in us, but sometimes the things that happen to other people also live in us.

Lily: I am working deeply with that in this second draft of my novel. Yesterday, my dad very sweetly texted and asked if I wanted to meet him at the tree where my mom's ashes are buried. We met there and he shared some things he was grateful for in my mom and I shared some things. And then he said, Is there anything else you wanna say? I feel very sober right now about my relationship with my mother in a way that I haven't in a very long time, in large part because of the kind of deification of the dead that often happens. And especially because I've written a lot about it and her. So anyway I was like, Yeah, I do. There is something else I want to say. And then I stopped, cause I was like, how can I say this in a way that my dad will understand, that he’ll really get it. And I said, I wish that she had been more accepting of herself. And my dad immediately was like, Yeah, that would have been great. Her parents were really tough on her.

And I was just like, Wow, that landed. Not just because I’ve been thinking about it and writing about it, but he felt it too, as someone who loved her witnessed her. And all of the ways that she was critical or hard on herself and him and me. To hear that it immediately took him back to her parents, like it immediately went to the intergenerational question, the intergenerational trauma. I was just like, Wow, I've never done that before. In this moment of remembering her, not just being present to all of the beauty and the love and wisdom that I received from her, but also really taking a stand for what I wish could have been different.

Eliza: So beautiful. Thank you. That feels like a perfect place to leave it. I so appreciate you talking to me you gorgeous, brilliant woman.

Recommendations

For more of Lily's brilliance and wisdom, you should absolutely subscribe to her Substack HERE. Lily also has a section of her website dedicated to resources for grief and loss.

I use her cookbook (and there's also a lot of really beautiful writing in here) all the time. I highly recommend Kale & Caramel: Recipes for Body Heart and Table.

What's Your Story? by Lily Diamond and Rebecca Walker. This journal helps you investigate your beliefs and identity, by two incredibly brilliant memoirists and writers. As described by its authors, What's Your Story? is an interactive journal for anyone who longs to bring a new story to life and leave behind the tired patterns of their past.

You can find links to a treasure trove of Lily's articles and essays here.

The book we talked about in this interview is The Wild Edge of Sorrow: Rituals of Renewal and the Sacred Work of Grief by Francis Weller.