Eight of Swords

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Have My Bottom Surgery with guest author Emily St. James

When I was a kid in the 1980s, I was dimly aware of trans people. Every so often, a Rénee Richards or a Christine Jorgensen would pop up in some book I was reading, and I would feel a tickle at the back of my brain. At that time, trans people were written about as something akin to the Mothman – fascinating curiosities worth gawking at but also possible harbingers of the end of the world. Either/or.

The primary focus of most writing about trans women focused on what was called the “sex change operation,” which was discussed in vague, hushed terms. I do not know what the authors of these books thought happened when a trans woman had “the surgery,” but the implication was always that the penis was cut clean off, and then a shallow gulch carved jack-o-lantern-style into what was left behind. These accounts allowed that this surgery was necessary for these poor women but also suggested that it was a tragic, terrible thing to do to a perfectly good penis.

Won’t someone think of the poor penises? is the underlying subtext of a lot of gender discourse on this planet of ours, and the omnipresence of the penis also completely warps how we talk about trans feminine people. When I was reading about Richards and Jorgensen, I was building an idea of how transsexuality – the term at the time – worked: You could not be a trans person until you had thrown your penis to the wolves. To have “the sex change” was to signify a seriousness of intent. It was to say, “This thing that so much of our society revolves around? I do not need it!”

Yet the operation was only written about in the most violent of terms. Even in articles that described more or less what happened, the language used implied a surgeon taking a hacksaw to one’s netherregions without regard for function or comfort. Our culture still writes about most trans surgeries in this fashion. There is little curiosity about what top surgery might mean for a trans masculine person or bottom surgery for a trans feminine one. There is only a certainty that what was once whole has been changed in a way both irreparable and sorrowful. Why, why why would you do this to a perfectly healthy body?

As a trans person, I obviously disagree with this framing. Trans surgeries are beautiful and necessary, and their invention is a triumph of modern medicine. Yet it was far easier for me to believe this in general than to believe it might be true for me. I was haunted well into adulthood by the supposed barbarism of bottom surgery, to the degree that I stopped myself from coming out on at least two occasions because I could never imagine doing that to myself, even though I knew how badly I needed to have the procedure. Even when I came out to my wife, I assured her I would never, ever, ever have bottom surgery. It grossed me out too much. It terrified me.

Then, after years of navigating medical bureaucracy – and three separate delays – I finally had what is technically termed a vaginoplasty. It was only after it was done that I let myself realize how badly that little girl reading about Richards and Jorgensen was thinking, Yes, please, me too someday, me too.

When making a tarot deck, it is common for the artist to offer their own take on the cards. The Emperor, say, might become a kind and just father or a cruel patriarch depending on how the artist feels about masculine rule. By its very nature, tarot invites interpretation. You can draw one of the darkest cards in the deck and find yourself comforted by it, depending on your personal circumstances at that moment.

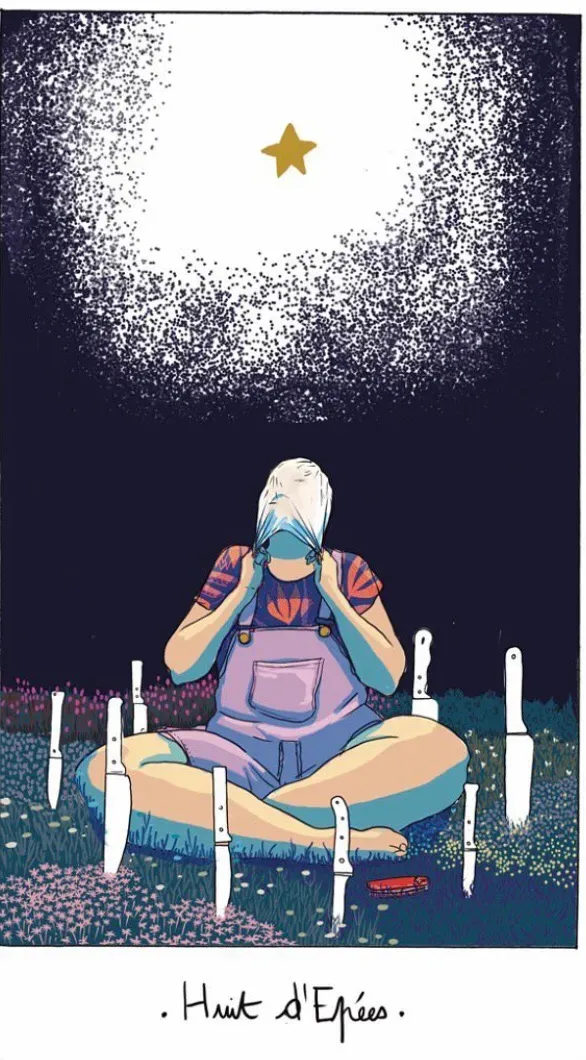

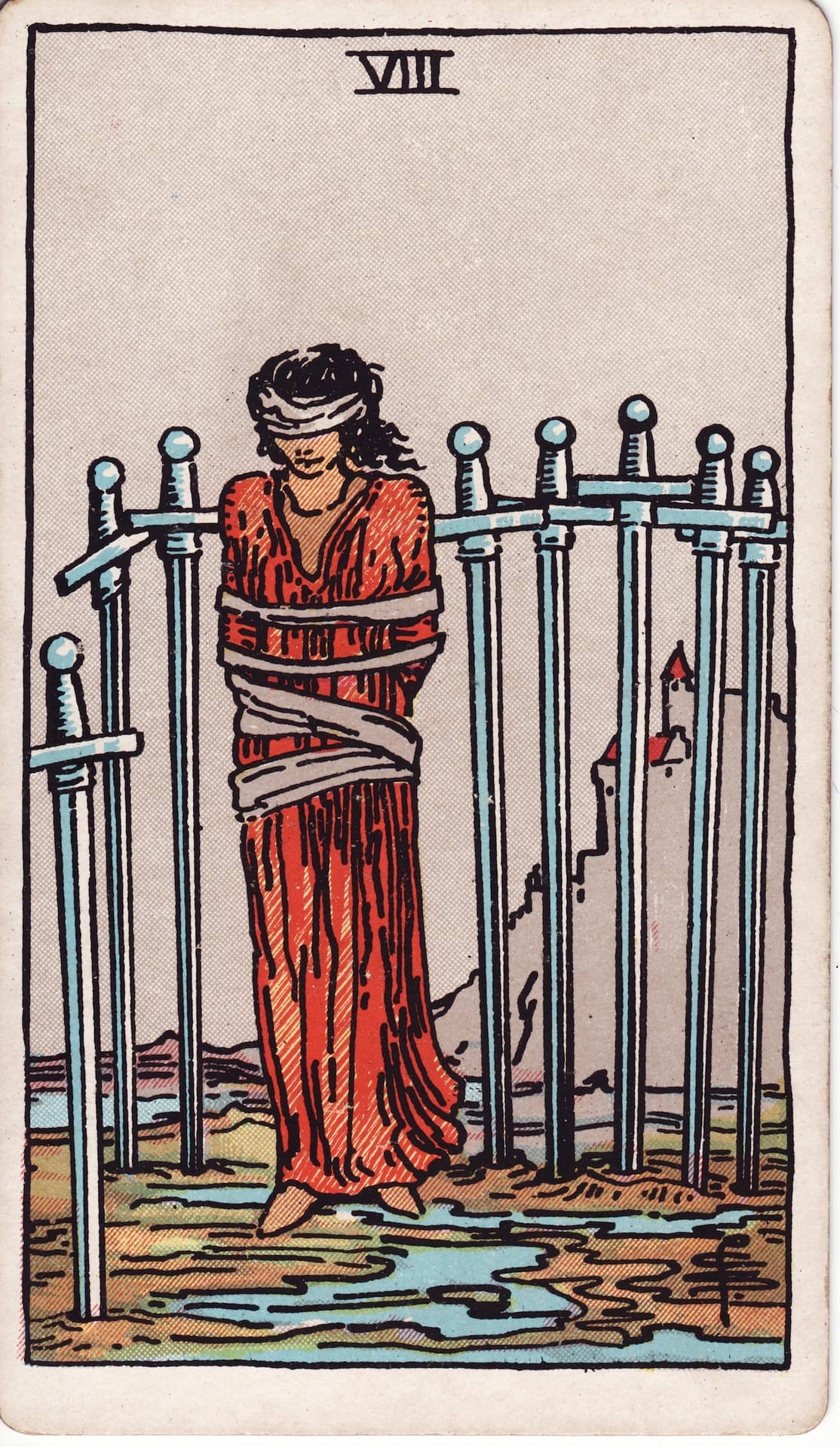

Yet there are some cards that resist artistic reinterpretation. This is not to say they cannot be reinterpreted but, rather, that certain images become so tied to them as to be almost inescapable. One such card is the Eight of Swords, whose depiction in the popular and familiar Rider-Waite-Coleman-Smith deck casts a long shadow over any Eight of Swords card one might make.

In the RWCS card, a woman stands in the center of eight swords that form a loose, circular boundary around her. She is bound and wears a blindfold. What becomes immediately obvious, however, is that the woman is not actually trapped by the swords. There is an enormous gap in the circle directly in front of her. Her legs are not bound, and if she took a few steps forward, she would discover that she is not in prison. Yes, she will still have to figure out a way out of her binding, which will not be easy, but wriggling her way out of the cords that hold her is a good deal easier than sliding between two razor-sharp swords. Of course, she cannot see that she is partially free. So she stands still, waiting for someone to come save her.

The image is a powerful one and so indelible that every other tarot deck has to reckon with it in some way, even if it opts to go in an entirely different direction with the card. Still, by far the most popular way to reinterpret the Eight of Swords is to depict someone or something in a blindfold. Like here’s a crow in a blindfold, for instance. Have you ever blindfolded a crow? It’s not easy.

The most popular interpretation of this card asks the observer a simple question: What prison do you live in that is not actually a prison? What escape routes are you missing because you are blinded to them? What are the steps you could take to escape this prison that don’t require other people to save you first?

Return to our crow friend, for instance. She’s actually surrounded on all sides by swords. She is also, however, a crow. She can fly! Yes, the cloth that binds her is around her wings, but it holds her only loosely. Should she stretch those wings outward, she would find that she could very quickly ascend into the sky. But doing so would require believing such a thing is possible, and so much of our world is built around convincing you that nothing big and radical is possible.

As Emily St. James writes in her novel Woodworking, “When you build a prison, you also create its escape route, no matter how hard you try to safeguard its walls.” In the context of St. James’s book (I am reliably informed), this remark is meant on an interpersonal level about a character longing to free herself from an abusive family. But how many other aspects of our world might this describe? How many other prisons have their escape routes hiding in plain sight?

So maybe the question the Eight of Swords invites is not “How are you holding yourself back from realizing your own agency?” Maybe the question is “Who tied the blindfold?” Because it sure wasn’t you.

The morning of my surgery, I felt a bone-deep panic. I was so sure that the procedure would be delayed yet again that I had not prepared at all for the idea of it happening, had not, in fact, really thought about it at all. It helped that I both released a book and had an episode of TV I had written air in the days leading up to said surgery, but even that busy schedule can’t account for my dissociate prowess, not really. The surgeon, I was sure, would decide after I had been anesthetized that she simply wasn’t going to move forward. She would wake me up by slapping me hard enough to cut through the general anesthesia, then kick me out of the hospital and send me on my way. Yet with every passing minute in the waiting room, I began to realize that, no, this was really happening.

For whatever reason, the thing that finally cut through the terror was my wife saying, “Did you know that at least some of the surgery will be done by a robot?” What she meant was that some of the most delicate work would be done by a machine supervised by the surgeon, but I couldn’t help but picture Wall-E and EVE in the operating room, doing their best. (It’s probably best Wall-E wasn’t involved. Have you seen the shit that guy gets up to?)

The more I thought about why this idea cut through my fog of fear, the more I realized that I had so deeply internalized the idea of bottom surgery involving a surgeon sawing off one’s penis, screeching, then throwing it into the sky for a hawk to swoop down and haul off to its aerie. For as many times as my surgeon – and others – had explained to me what the procedure actually entailed, my old fears were hard to budge. Knowing that something as modern as a robot would be involved helped jar my mind loose from the track it had been on since my childhood. It made bottom surgery feel not just possible but preferable to the status quo I had been grinning and bearing my whole life. What I realized was that while I was altering my body, sure, I wasn’t really removing anything major.

I’m about to describe how bottom surgery works. I’m not going to get super technical because I’m not that kind of writer, but if you really just don’t want to know anything about it – beyond that it does not, in fact, involve the cutting off of a penis – skip the next paragraph.

The principle behind vaginoplasty is based on the fact that the penis and vagina are remarkably similar organs that simply head in different directions in late gestational development. To be overly simplistic, the vagina heads inward, while the penis sprouts outward. Thus, a trained surgeon can take the penis and turn it inside out, more or less, inverting it to create a vaginal canal, then supplementing everything with scrotal skin. (The testicles are, indeed, removed. No word on if they are given to the hawks.) Skin is usually taken from elsewhere on the body to complete the process – mine was from around my belly button – but for the most part, everything the surgeon needs is right there to begin with.

In other words, everything my body had needed was already there. Nothing was being removed or taken away. Everything was, instead, being reimagined and reinterpreted and rethought. The popular conception of trans bodies among cis allies is that we are “born in the wrong body,” but this idea subtly undergirds the thought that bodies are not, in fact, changeable, when, in fact, transness shows that you can change the body in so many ways you might not be cognizant of. My body has estrogen and testosterone levels similar to a cis woman’s. It has breasts I grew myself. It now has a vagina that functions basically the same as any other vagina, with a few minor differences. Like, yes, I had to relearn how to pee, but that didn’t take me very long, and now I’m peeing like a champ.

My whole life, I had gone along with the blindfold placed around my eyes by a society that shudders at the thought of such a procedure (probably because it prompts a sudden, intense revulsion not unlike gender dysphoria for gentle-hearted cis people), when, in truth, I had always had every single thing I needed to step out of prison. When I woke up, groggy, after the surgery, I barely knew anything had happened. When the nurses and surgeon removed my bandages a few days later, I simply felt completely fine, with barely a seism of pain to mark my “altered” body. I knew, intellectually, that something had changed, but I didn’t feel an absence because there was none to begin with.

Yes, recovery has been arduous. For a couple of weeks, just the thought of walking around my apartment building floor felt so enormous I could hardly comprehend it. I spent a lot of time on the couch, eating junk food and watching the Wheel of Time TV show. (It’s good!) Even so, I’ve been amazed at how elastic my body is. Recovery has felt like it’s traveled along a steady upward curve, slowly ascending at first, then skyrocketing. Even my vagina’s ability to heal and adjust has been remarkable. I spend 10 minutes every morning, afternoon, and evening dilating my vaginal canal so that it slowly stretches and gains the shape I need. The first time I tried to do it without a doctor’s assistance, I cried from how frustrating I found the process. But every day, it gets smoother, easier. The size of dilator I use ticks ever upward.

The above paragraph underlines the steps I’ve had to take in this matter, which makes it sound like I’m on some sort of constant learning curve. I suppose that is technically true, but I am also struck by how rarely I remember that I had surgery almost six weeks ago. Except for the moments when I can, say, feel the strain on my few remaining stitches or when a few of the nerve endings down there turn back on and scream at me briefly before getting with the program, it feels like nothing happened. It is easy to tell myself this is how my body has always been because to some extent it always has. The blindfold fell away, and I realized I had always been capable of flight. I just had to remind myself of that fact.

I do not mean to suggest that all binding is so easy to remove. We live in a broken, warped world, and fixing much of it will require more than the power of believing in oneself. Still, the blindfolds that obscure our view and the ropes that pin our arms to our bodies are real. What might happen if we had the faith to take a few steps forward and then a few more? Would we realize we were never imprisoned in the first place? Would we learn who had bound us to begin with? So much of what we have been asked to accept as normal is, instead, deeply abnormal. All that it takes to understand this, sometimes, is taking not a leap of faith but a single step.

Emily St. James is one of my favorite writers in the world (also one of my bffs). She writes for Showtime's Yellowjackets, and recently published my favorite novel of 2025, Woodworking. You can find more of her writing here (and I recommend that you subscribe immediately).